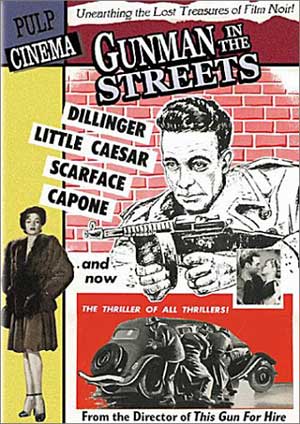

A strange confluence of talents and an odd moment in history are as responsible as anything else for the English-language Gunman in the Streets, (1950), a hardboiled, occasionally thrilling, and visually entrancing Franco-American crime thriller that for some unknown reason, was never distributed theatrically in the United States. Among its several attractions is a 29-year-old Simone Signoret, just off her role in Max Ophüls’s La Ronde, and, in what would be a very brief moment in her career (Les Diaboliques was four years away), still combining a raw sexiness with youthful innocence. Releasing through Image Entertainment, All Day Entertainment has put all this together in a nice DVD package, highlighted by a very nice print of the movie.

A strange confluence of talents and an odd moment in history are as responsible as anything else for the English-language Gunman in the Streets, (1950), a hardboiled, occasionally thrilling, and visually entrancing Franco-American crime thriller that for some unknown reason, was never distributed theatrically in the United States. Among its several attractions is a 29-year-old Simone Signoret, just off her role in Max Ophüls’s La Ronde, and, in what would be a very brief moment in her career (Les Diaboliques was four years away), still combining a raw sexiness with youthful innocence. Releasing through Image Entertainment, All Day Entertainment has put all this together in a nice DVD package, highlighted by a very nice print of the movie.

Naturally, image quality would be the central attraction in any case, but this is especially so here since the major talent behind Gunman is the rightfully legendary cinematographer Eugen Schüfftan (aka Eugene Shuftan, or in various other permutations with or without the umlaut or second "f" in his second name or "e" in his first). At age 36, Schüfftan had been the director of photography on that bit of bitter Berliner realism, Menschen am Sontag (People on Sunday) (1929), a film that would launch such a varied set of careers, including that of co-directors and co-writers Robert and Curt Siodmak, co-director Edgar G. Ulmer, co-director (and camera assistant) Fred Zinnemann, and co-writer Billy Wilder.

The careers were varied, of course, because everyone beat it out of Germany after Hitler rose to power in 1933. Schüfftan began a long odyssey through Europe, during which time he worked in England and, mostly, in France, where he had the chance to collaborate with Marcel Carné (Quai des brumes) and Ophüls (Sans Landemain), among others.

Gunman represented a return to French soil for Schüfftan after a remarkable decade in Hollywood, where, though unable to get a cinematographers guild card, he had worked pseudonymously, again with Ulmer and with Douglas Sirk (Hitler’s Madman, Summer Storm, A Scandal in Paris) while the two émigrés were on Poverty Row and Faded Gentility Street respectively. At least one Ulmer- Schüfftan collaborations, Bluebeard, is reviewed elsewhere in this section, so you can read more about it there. And, if you want a list of the cinematographer’s accomplishment’s post-1950 accomplishments, you can check out his page at the Internet Movie Database.

Gunman in the Streets shows how adaptable Schüfftan could be. After years of working on inexpensive sets, the cinematographer found himself given the run of Parisian streets under the rein of director Frank Tuttle. Schüfftan not only took the streets as if he hadn’t dedicated himself to 20 years of imaginative studio work in the years since Menschen, but did it without sacrificing the suggestive, difficult lighting adjustments that, apparently, he could make anywhere.

Tuttle deserves a word or two here. A Paramount contract director from 1922, Tuttle has gained some renown over the years for directing the atmospheric adaptation of Graham Greene’s A Gun for Sale, This Gun for Hire (1942) (which was also Alan Ladd’s starring debut). With its sympathetic portrait of a paid assassin and correspondingly acid portrait of corporate manipulators, the movie has struck particularly strong chords with modern audiences. But is the director of Big Broadcast (1932), Springtime for Henry (1934), or Charlie McCarthy – Detective (1939) really the auteur of Gun for Hire? True, Tuttle did get handed a Glass Key (1935) now and then. But the dark, low-key look of This Gun is far more in tune with the visual style of cinematographer John F. Seitz, a specialist in darkness and shadow, who shot the movie in-between shooting Preston Sturges’s Sullivan’s Travels and Albert Lewin’s The Moon and Sixpence.

Similary, This Gun for Hire benefited from a script by one of Hollywood’s toughest tough-guy writers, W.R. Burnett, a novelist who had written The Asphalt Jungle, Little Caesar, and High Sierra, and who occasionally wrote or collaborated on screenplays as a dialogue specialist (Scarface, The Man I Love).

Albert Maltz also worked on This Gun’s screenplay, and he and Tuttle probably has fun comparing their years both at the Yale School of Drama and in the Communist Party, USA. Maltz would go on to defy the House Committee on Un-American Activities, become a member of the Hollywood Ten for refusing to name names, and land on the Blacklist, unable to work under his own name. Tuttle, on the other hand, cooperated with the committee, named a lot of names, and ended up on a Grey List, kind of, sort of unable to work. Gunman in the Streets had come after a four year hiatus.

So here was everyone: Tuttle, Schüfftan, and Signoret (whose father was Jewish, by the way, and so had spent WWII in London, which is why she spoke English). Oh, yes, Dane Clark, who played the film’s anti-hero and, singularly unencumbered by a past, was fitting the movie in among a Hollywood Western, melodrama, and mystery he was doing in the same 18-month period. To add a coincidence, Clark – a good, sad-eyed actor who turns in a very good performance – Clark had performed for Tuttle in The Glass Key under his real name, Bernard Zanville.

And here’s the opening of Gunman, a scene that has very little to do with Tuttle, one would assume, but a whole lot to do with Schüfftan. Eddie Roback (Clark), a nearly psychopathic former American serviceman turned armed robber and murderer, is being transported through Parisian streets via an armored car and under heavily armed escort. Still, the local prefect thinks that all that police presence might not be enough and he’s right; Eddie’s confederates have planned a daytime ambush on a busy downtown street corner, one that comes off amid a fusillade of bullets and the smoke of explosions. When Eddie breaks out of his van, he immediately displays his vaunted brutality, eagerly shooting cops with a seized pistol and kicking a man lying on the ground right in the head.

It’s a spectacular action scene, quite unlike anything else being done at the time. The scenes of mass carnage and individualized action is shot with superb tactical deployment. Yet there’s a lingering moral horror throughout the sequence, a split sense of sympathy between escaping prisoner (who is nevertheless a psychopath) and suffocating authority (which is still a "Free France"). That all this comes across in the imagery points away from Tuttle and towards Schüfftan – it requires that while everything is going on, we get a good look at Roback’s face, and faces were always something Schüfftan got a good look at.

Not that the cinematographer couldn’t whip up an image of classic romanticism imbued with his own twist. In one scene, Signoret’s character, Roback’s old girlfriend Denise (who spends the entire movie running around in an ankle-length fur coat), looks through a broken window pane to watch a (new? old? we can’t give the game away) lover wander off, perhaps forever. The pane is not only broken, it’s dirty, too, and it provides the perfect perspective for this sad occasion. But to keep the image from becoming too cold, Schüfftan has Denise slide her gloved hand up the side of the glass. Of course, given Signoret’s wardrobe this is a ridiculously glamorous gesture. But Schüfftan’s persistence in humanizing Signoret/Denise (it’s hard to say the narcissistic Signoret wants us to consider a difference) also pays off in a humanizing presence. That composition through the glass, that gloved hand, do indeed add to something more emotional, more indentifiable, than what we’d get in, say, a plain, big-budget Warner Bros. melodrama of the same period.

Gunman in the Streets has a plot, though like most plots, it serves mostly to distract us from a movie’s more honest virtues. Over a 24 hour period, Denise must raise 300,000 francs so that Eddie can make his way from Paris to Belgium and freedom. In typical French fashion, Denise ends up getting the money from a man who is in love with her and despise Eddie, but who wants to make a symbolic gesture (atypically, and improbably, the man is not only English, but a journalist).

What matters is that a romantic trio – psychopath, siren, a reporter (who is played by Robert Duke, an unknown to me) – head off the Belgium and, obviously, a final showdown. Before they leave Paris, there are two moments of note. In one, Eddie taunts and tortures an underworld ally whom he is sure betrayed him. While the scene has some claustrophobic value, and is lit very well, it is largely notable in for the filmmakers’ confused attempts to introduce anti-homosexual elements into the film. First, they suggest the backstabbing character is homosexual by giving him a cat and a smoking jacket. Then, however, he makes an aggressive pass at Denise. This to-and-fro keeps up in an increasingly pointless way until, finally a line of dialogue confirms that, yes, the fellow is homosexual. A lot of trouble for a minor point.

A far greater scene occurs in a restaurant where Denise – let’s just call her Signoret – tries to shake her police tail by meeting the journalist for dinner. Confident that her watchers are only keeping an eye on the fancy eatery’s front door, Denise bids her temporary partner adieu and gets up to leave. Her departure, thanks to Schüfftan is magnificent, a moving shot that follows Signoret and the lighting changes the accompany her as she walks across the floor of what must have been one of the largest restaurant’s of post-war Paris. It’s a study in the intricacies of beauty.

The problem with Gunman in the Streets is that, unless and until Schüfftan finds other settings worthy of Signoret, there’s not much of anything going on. Compositionally, the movie is completely based around her presence, frequently triplets with her in the center, lit like a Madonna and dressed in a black evening gown. The opening action scene is by far the best in the movie. The climax, which is preceded by a nice sequence in a warehouse, looks like its going to be a furious shoot-out, but it’s disappointing in its violence – though not in its sense of romantic completion.

If you’ve never seen what’s called a "cinematographer’s movie," though, this is a good place to start and a good one to own. As I mentioned, the print quality is very good, so Schüfftan’s work is shown to its best advantage. Among the extra DVD features are a collection of clips the British censor eliminated for public showing in the UK. Those clips are all in the film, of course, but it’s interesting to see what an English blue nose looks like in action. And there are also production notes about just what happened to the movie after it was finished.