Is it art or entertainment? Do we respond the exaltations of the muses or the demands of the bankers? Hollywood has always been bedeviled by these questions and not just on the inside, where directors and writers face off against producers and executives. Even audiences wonder whether the comedy they’re laughing at is a proper response to a world in torment.

Is it art or entertainment? Do we respond the exaltations of the muses or the demands of the bankers? Hollywood has always been bedeviled by these questions and not just on the inside, where directors and writers face off against producers and executives. Even audiences wonder whether the comedy they’re laughing at is a proper response to a world in torment.

Imagine how fraught a problem that was in 1942, when the U.S. was not only at war, but the Great Depression was not yet a memory. Oddly, this date marked the midpoint of one of the greatest rolls in comedy history, the seven movies the writer-director Preston Sturges made between 1940 and 1944.

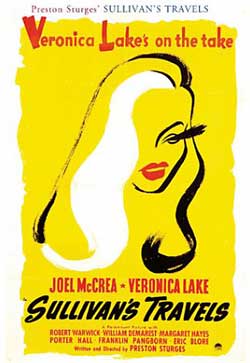

It was then, Sturges made "Sullivan’s Travels," a comedy about an A-list Hollywood director who decides he’s tired of making lighthearted frolics like "Ants in Your Pants of 1939." He wants to make a political drama called "O Brother, Where Art Thou," based on the struggle for social survival.

In one of the funniest scenes ever made for movies, and in a perfect example of Sturges’s gift for dialogue, the director, John Sullivan, played by Joel McCrea, tries to convince two studio executives, played by Robert Warwick and Porter Hall, of the wisdom of his desire.

"Sullivan’s Travels" is not a forgotten or lost film by any means; no movie with dialogue like that could vanish from cinematic memory. But a recent DVD release of the film from Criterion – complete with a documentary about Sturges and some old tape of him singing at his home piano – suggests that it’s a richer movie than generally believed. It’s much more than a cynical, if hilarious, retort to privileged filmmakers who would assume to speak for the downtrodden.

"Sullivan’s Travels" is actually a modern-day "Candide," only the apparently worldly director turns out to be the naïve traveler and his experienced guide is a young woman disappointed in an acting career.

Sullivan meets The Girl, played by pouty-voiced, peek-a-boo blonde Veronica Lake in the film’s middle portion. It’s a joke, of course, that The Girl never in fact gets a name, a clue that Sturges is breaking his movie down into bits of convention so that he can build it up again. Over the next half hour, the Girl teases the director out of his self-congratulatory pomposity and, through love, brings him to a more humane selflessness.

But Sturges’s ideas of comedy had a classical bent. Sullivan has angered the gods with his pride and he must be brought down. And so the movie’s final third is dark and somber though, like the rest of the movie, loaded with irony. Sullivan mistakenly ends up sentenced to a Southern prison work camp, a familiar film setting of the 1930s. There he learns that abstractions like justice – an abstraction he thought he could put on film – have no meaning outside of human behavior, and that the key to improving that behavior is love, in all its varieties.

That kind of sentiment is the last you might expect from a filmmaker with Sturges’s reputation. A brass-knuckled satirist, he attacked American pieties about sex and politics with an unmatched fervor. But a satirist needs double vision, one eye to keep on humanity’s foibles, another to fasten on its possibilities. In "Sullivan’s Travels," in a time of national struggle and fear, Sturges could see both without ever getting cockeyed.