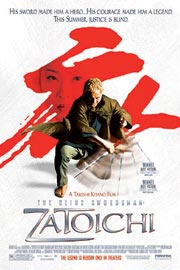

In the credits for The Blind Swordsman: Zatoichi, his remake of the 1962 period yakuza film, The Tale of Zatoichi, Takehsi Kitano (who stars and directs) bills himself under his comic nom de theatre, Beat Takeshi. Long before he directed masterpieces like Hana-bi, Takeshi was one of the Two Beats, so-called manzai comedians whose act (so I’ve read) was something like a Three Stooges with two Moes, only Moe is played by Redd Foxx. From there, as Beat, Takeshi went on to become a huge Japanese TV star, (again, so I’ve read) partly based on comedy shows at least partly distinguished by their cruelty, sexual frankness, and crudity (not that there’s anything wrong with that).

In the credits for The Blind Swordsman: Zatoichi, his remake of the 1962 period yakuza film, The Tale of Zatoichi, Takehsi Kitano (who stars and directs) bills himself under his comic nom de theatre, Beat Takeshi. Long before he directed masterpieces like Hana-bi, Takeshi was one of the Two Beats, so-called manzai comedians whose act (so I’ve read) was something like a Three Stooges with two Moes, only Moe is played by Redd Foxx. From there, as Beat, Takeshi went on to become a huge Japanese TV star, (again, so I’ve read) partly based on comedy shows at least partly distinguished by their cruelty, sexual frankness, and crudity (not that there’s anything wrong with that).

Takeshi’s Zatoichi isn’t anything like what his TV shows sound like, but it is a casual burlesque of the original film, which spawned a series that produced two or three films annually for about ten years. Whereas the originals mixed swordplay and sentiment, Takehsi adorns his action with broad slapstick. Indeed, in the very first scene, one of Zatoichi’s enemies draws his sword, only to severely wound one of the comrades standing next to him, who in turn reacts with a buffoonish gag response. It’s a pretty clear signal that nothing that follows has to be taken seriously.

Is Kitano doing to the period yakuza film what Seijun (Tokyo Drifter) Suzuki did to the contemporary version beginning in the 1960s? It would be hard to see why. Although modern-day yakuza outings featured recognizable modern gangsters caught up in oppressively (for Suzuki) repetitious plots, period yakuza films were markedly different. Those yakuza were loners and gamblers who had emerged from the lower classes and though they had a code – ninkyodo – to which they were nominally loyal, in fact they invariably spent their time helping villagers and the like stave off the depredations of feudal lords and their henchmen.

On top of that, there simply wasn’t the onslaught of period yakuza films to match the flood of the modern variety. The Zatoichi series, which starred the ugly-handsome Shintaro Katsu, was the exemplar. The blind Zatoichi was a former masseur, an extremely low-status occupation, who had taught himself a form of sword fighting particularly apt to his situation (though blind, his other senses were extremely well-developed, and he kept his sword hidden inside his cane). He had become a gambler, roaming from town to town and (crooked) dice game to game (one of the pleasures of the series was watching him catch the cheaters), hiring his sword out to the wealthy who needed it, but always forfeiting his fee for the sake of helping the downtrodden. (This formula would undergo a hallucinogenic, ultra-violent mutation in the 1970s with the Perambulator series, marketed in video in the U.S. under the title Lone Wolf and Cub.)

The Tale of Zatoichi set the template for the 20-odd pictures to come, so for Kitano to pick that particular film to remake is not particularly telling. What is telling is how he changes the film.

For example, in the 1962 film, Zatoichi is hired by a gang of crooks about to go to war with some rivals. The rivals, for their part, hire a ronin, or masterless samurai. Already in reduced circumstances, the ronin has fallen even farther down the social ladder thanks to a well-advanced case of tuberculosis. But he and Zatoichi recognize each other as kindred spirits and they have several significant, quasi-philosophical conversations, cooperate on matters tangential to their employers, and have a final confrontation both keen and poignant.

Takeshi, for some reason, gives the ronin a girlfriend and gives her the case of tuberculosis. Thus the ronin’s own fall from grace is, if not eliminated, at least ameliorated, and with it much potential drama. Worse, rather have the now more mildly suffering warrior relate his distress to Zatoichi in conversation, Takeshi shows it in flashback, thus guaranteeing that no relationship is built between the two.

Takeshi invents a semi-camp subplot featuring two deadly geishas (at least their called geishas in the subtitles, though through their actions they appear to be prostitutes) that is more indicative of the movie’s general tone. The pair is in fact the remaining survivors of a noble family whose wealth was coveted by the ronin’s employer, the vulgar gang leader Ginzo. Having witnessed the murder of their parents as children from a hiding place, they had dedicated the rest of their lives to vengeance, finally converging on Ginzo just as the ronin and Zatoichi do.

While Zatoichi, the ronin, and the vengeful sisters represent the three main strands of the plot, they are hardly the only ones, and Kitano the complex narrative flow with aplomb. Moreover, he habitually inserts sudden flashbacks to delve into characters’ motivations, yet manages to do so without sowing confusion or, indeed, impeding the film’s forward current.

But while there’s a technical commitment to the action, an air of intellectual ennui soon settles over the whole project. The sword fights are bloodily effective, but you never know when they’re going to descend into mere low comedy; because of that, they lose their excitement. As the movie goes on, some of the characters become, not ridiculous so much as absurd; un-characters in a way. The greatest victim of this turnabout is Zatoichi himself, whose very identity is thrown away by Takeshi at the climax.

You can’t call The Blind Swordsman: Zatoichi a failure because it’s not even clear what Takeshi set out to accomplish. One does suspect from the breakdowns in character, though, that it may have been a project he lost interest in once the cameras were rolling. At any rate, it’s another whiff from a filmmaker who increasingly specializes in them.