Kathryn Bigelow’s extraordinary command of subjectivity has always been her outstanding talent, one which has made her a peculiar and peculiarly contemporary variant on the under sung (and underemployed) Robert Mulligan. Whereas Mulligan mostly assumed the viewpoints of young people caught up in some entanglement of love, Bigelow prefers her young adults to get mixed up in violence, preferably lethal violence. And only K-19: The Widowmaker, Bigelow’s most recent movie, lacked a bristling psycho-sexual element to the violence (no, I’m not forgetting Point Break).

Kathryn Bigelow’s extraordinary command of subjectivity has always been her outstanding talent, one which has made her a peculiar and peculiarly contemporary variant on the under sung (and underemployed) Robert Mulligan. Whereas Mulligan mostly assumed the viewpoints of young people caught up in some entanglement of love, Bigelow prefers her young adults to get mixed up in violence, preferably lethal violence. And only K-19: The Widowmaker, Bigelow’s most recent movie, lacked a bristling psycho-sexual element to the violence (no, I’m not forgetting Point Break). The Weight of Water brings those psycho-sexual elements back in spades, though in a languorous, adult-melodrama way reminiscent of early-‘60s Losey; you might keep waiting for Dirk Bogarde to show up in the film’s modern sequences. Set off the coast of New Hampshire, the film avowedly has two parallel stories tied together in part by a voice-over by a photojournalist, Jean.

The anchoring narrative takes place aboard a comfortably large sailboat taking Jean to a New Hampshire island where, in 1873, two women were murdered and a third assaulted. A man was hanged for the crime, but a lingering mystery has hung over the case, the reason a magazine has assigned Jean to take the photos. The job is also a vacation, though: Jean’s taking along her husband, a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet, Thomas, and the boat is owned by Thomas’s brother, Rich, a charter captain, who is also bringing along his girlfriend, Adaline.

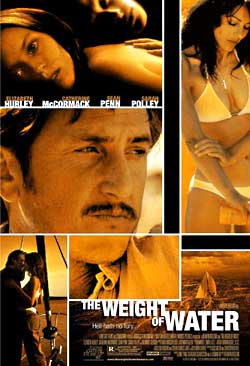

Naturally, everyone is either sexually alluring or, at least, sexually available. Jean is played by the lovely Catherine McCormack, while poet Thomas is undertaken by Sean Penn. Rich is portrayed by Josh Lucas, a former male ingénue graduating to younger brother status, while personality Elizabeth Hurley does Adaline, wearing a revealing bikini when she bothers to wear anything at all.

Admittedly, two of the performances are highly problematic. Hurley, who is hardly an actor, at least has the excuse of her amateur status. Penn, whose claims to greatness rest largely on the effusions of the excitable popular press, retreats to mimicry that marks most of his career. Having decided that poets scratch their chins, mumble and smoke, he proceeds to do just that for the whole movie. Unforgivably, the two are given poetry to recite to one another. Less unforgivably, the two also spout critical and philosophical nonsense, but this may be to underline their pomposity.

All this is easily overlooked, the vagaries of acting and dialogue which are the unavoidable dishonesties of modern cinema. What matters most is mise-en-scene and editing and in these areas Bigelow’s efforts soar above trivialities.

As you might imagine, with Adaline frolicking around in the semi-buff, flirting with Thomas and with the two of them revealing to Jean that they had met in the past, tensions begin to grow. Bigelow’s depiction of this, through inventive camera placement and cutting goes beyond efficient to the superb. Intellectually incisive and emotionally riveting, it shows us a superficially calm and collected Jean sliding into an emotional abyss.

This brings us to the 'parallel' story, the events depicting the crime, which have already begin to emerge. Again, the events revolve around a single personality, this time Maren, a young Norwegian bride brought to a desolate New Hampshire island by her older, taciturn, if loving husband. She dutifully performs her wifely obligations, even taking care of her crabby older sister, Karen, when she arrives. But she breaks into something approaching bliss when her handsome brother Evan arrives, though that bliss is strangely reined in when it turns out he’s brought a young bride, Anethe with him. Though life on the little island – Smuttynose is its appropriately redolent name – is a great deal more repressed than it is on the sailing boat, it turns out there is a great deal more to be repressed, and when the repressed returns, it’s with a vengeance.

Oddly, the island story, though it’s restricted to a clapboard house and rocky offshore upcropping that barely deserves the name island, doesn’t have nearly the claustrophobic atmosphere that the modern, boat-borne side of the film does. And this despite the fact that the voyagers get off the boat at least twice, once when Jean visits the local archives and once when she swims ashore Smuttynose.

Partly this is due the comparative breadth of the action. There’s a steady stream of characters joining Maren and her husband and steady rise in our expectations of violence (both stories are told in flashback). Then, too, the acting in these sequences is much better. The young Sarah Polley is yet confident enough to be still and quiet in her acting and the role of Karen is grist for the mill of Katrin Cartlidge (sadly deceased since the film was completed). Ciaran Hinds, who plays the German fisherman hanged for the murders, is better than any other male performer in the film.

But the expansiveness has another source. The two story lines do seem parallel, with roughly similar plots building to nearly identical emotional climaxes and dire consequences. But the The Weight of Water makes more sense if both sections of the film are regarded as scenes refracted through Jean’s mind. It’s not that what we’re seeing didn’t happen to one extent of another. It’s just that – as the climaxes confirm – what is seen is either obscured or sharpened by sensibility, even transient sensibility. What may be enlarging the 19th-century episodes is the force of Jean’s imagination, the velocity of transference. If that is what’s going on, than what Bigelow has done goes very much beyond craft.

Fans of Bigelow might be glad that Weight was held up because it lets them see an 'authentic' Bigelow after the commercial compromises of K-19. The authenticity comes in the violent entanglement, that coupling that makes her at once similar to and different from Robert Mulligan. It’s funny, but in Mulligan’s films, when two people fought their way through romance or other brutal forms of love, it was so each could end up more strongly individual on the other side. Natalie Wood in Love With the Proper Stranger, had to throw off her family’s defining expectations of her and be herself before she could end up with Steve McQueen. Bigelow’s characters, though, go through strenuous, almost torturous resistance to maintain an individuality they may toss aside when it’s no longer under assault. Or not.

Bigelow herself never seems to know what her characters are going to do or why – become vampires or stay human, stay cops or go crooked, be men or women. Some viewers like the sense of spontaneity of open-endedness this gives her film. But the same self-conscious skepticism that leads her down that path, also lays Bigelow open to charges of genre overkill. Some of us think that, in a world that celebrates The Matrix, picking out the director of Strange Days for such a charge is absurd. So it will be interesting to see what the observers who swoon over the glorified classroom exercise, Far from Heaven, will make of the living The Weight of Water.