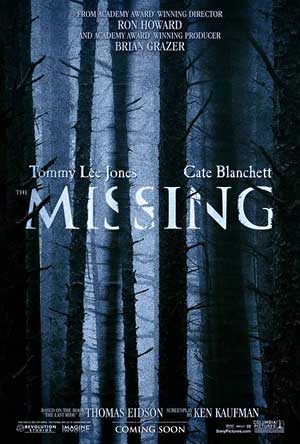

Ron Howard’s The Missing is a throwback to the days of the bloated Western, an era that began no later than 1958 with The Big Country and dribbled on through the 1960s (The Sons of Katie Elder) and into the 1970s (Cahill – United States Marshall).

Ron Howard’s The Missing is a throwback to the days of the bloated Western, an era that began no later than 1958 with The Big Country and dribbled on through the 1960s (The Sons of Katie Elder) and into the 1970s (Cahill – United States Marshall).

Bloats weren’t the only Westerns made at the time, thank heavens. Howard Hawks (El Dorado) and John Ford (The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance) were still filming masterpieces, while Sergio Leone was ferrying Clint Eastwood through the spaghetti wilderness. But the bloats dominated the commercial field and their influence was everywhere; The Wild Bunch comes just this close to being a bloat but for Sam Peckinpah’s despondency.

You can see how the urge to make a bloat – call it Shenandoahitis – would appeal to Howard, the eternal juvenile. Both the filmmaker and the genre confuse the notion of maturity with being “grown-up.” Grown-up is a wonderful phrase because it is so a-synonymous with “adult.” The word adult implies a stage of growth while grown-up implies stasis, a human being frozen in the posture of authority. It’s a children’s term establishing a children’s perspective. If you’re grown-up, you’re done. There’s nothing left but to exercise your repetitive reflexes.

Repetitive reflexes: Welcome to the world of The Missing. The tip-off that we’re in for automatism comes right away through the cinematography of Salvatore Totino, a workman fitting a feature into his busy schedule of television commercials. Basically, we get two types of shots: The over-composed long shot and the screen-hogging, mise-en-scene-less close-up.

Naturally Howard is behind the man behind the camera, but Totino deserves special credit for the sheer lifelessness of his panoramas. Nearly every composition is purely lateral, crossing the frame without ever reaching out to the viewers or pulling them in. Totino uses none of the simple compositional strategies – having a hill roll down to the audience, or using multiple planes – that would invite the audience into the action. And while one could make a case for the suitability of his cold grays and blues, their combination with the flattened-out landscape only furthers the sense that everything has been wrapped in cellophane.

The story, too, has come out of the cinematic automat. Cate Blanchett, fussy accent at the ready, plays Maggie Gilkeson, the widowed owner of a small ranch in the southwest U.S. (or, as the press blare, “the American Southwest”). Alone with her two young daughters but for one handsome hand (Aaron Eckhart) and one cantankerous one (Sergio Calderon), she supplements her subsistence livelihood by curing locals of mino ailments.

Into this little sodden paradise rides Jones, a man who superficially resembles an Indian but who is actually Maggie’s biological father. Since Jones abandoned her mother, Maggie is understandably unhappy to see him and, after tending to a wound he complains about, ushers him off the property. Unfortunately, soon afterwards, a band of Indians led by a psychopathic medicine man (Eric Schweig) murders the two hands and kidnaps Maggie’s teenaged daughter. Maggie and the younger kid hit the trail in pursuit, drafting Jones as accompanying scout, fighter and penitent.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with this material. Captivity sagas are a mainstay of Westerns, the foundation of Ford’s canonical The Searchers and of such appealing curiosities as Robert Mulligan’s The Stalking Moon. But you have to pull some ore out of that ground or, if you’re set on being superficial, at least dance lightly and quickly upon it.

Howard does neither. For starters, he does nothing to rein in the worst habits of his stars, Blanchett and the horrifyingly awful Tommy Lee Jones, who plays Jones. There was a time when Jones was a provocative performer, but whatever the exact moment he gave up acting for memorializing himself was, he’s been an annoying wind-up toy since The Fugitive. Using his voice’s upper register, speaking lines on an upward scale when downward would be conventional, stuttering his physical gestures – all these over-familiar tricks are indulged no matter what they might have to do with the ostensible matter at hand.

While Jones and Blanchett are over-registering, everyone else in the movie is barely registering at all. As usual, Howard has trouble bringing supporting characters into sharp focus. Part of that goes to his conception of character, which relies heavily on costume or physical tic for identification but usually stops there. The salient feature of Schweig’s bad, mad Indian isn’t his hatred for encroaching white settlers or even a desire to make money selling women off to Mexican pimps (how’s that for a nice racist one-two punch?). No, it’s his bad teeth. If we are to go by the visual clues Howard gives us, we could only assume that a couple of root canals would have left the medicine man happy and contented on the reservation.

But it’s more than that. Howard has been working with the same editing team since Night Shift, so it must be that one and all are happy with the lack of communal coherence that infects all their collaborations. You get more than three people into a scene in a Howard film and everything goes haywire. So-and-so is over there, no, wait a minute, he’s over here how’d he get back there again? This uncomfortableness with dramatic space is usually a TV problem, but Howard brings it to the big screen.

Anyway, bloats can’t be bothered with the niceties of space after they’ve finished with the big postcard shots. They’ve got bigger fish to fry: The Big Theme. The Missing’s Big Theme is Reconciliation Between Father and Daughter. And come hell or high water (literally for the latter), Maggie and Jones are going to Reconcile no matter how little sense it makes.

And they do and it doesn’t.