So maybe it’s less important that Anderson’s films dwell almost maniacally on the problematic relationships between fathers or father-figures and sons (or, in one case, daughter) than that they do so with self-conscious bashfulness. Even when the larger-than-life characters (Gene Hackman’s Royal Tennenbaum in The Royal Tennenbaums or, in the new The Life Aquatic, Bill Murray’s Steve Zissou) find themselves momentarily boastful over a vaunted achievement, they immediately thereafter find themselves excusing some slip up inextricably bound up with the glory.

And the sons, or sons manqué – well, their senses of accomplishment are so meager as to render them almost emotionally supine.

That Anderson depicts there off-balance characters with such minimal fuss often obscures how sophisticated that depiction is. Most viewers have probably noted that the director is fond of horizontal compositions, in which two or more characters array themselves across the frame, they and the background at sharp right angles to the camera. Sharp viewers may even note that Anderson’s favorite camera movement is the parallel track, the camera moving laterally and lengthening, rather than altering, the composition. And true Anderson-philes have no doubt been delighted by his combination tracks-and-pans or crane and boom shots, which extend the frame even more. Combined with the filmmaker’s penchant for having characters enter and exit at the side of the frame, these techniques have the effect of an opened door revealing a secret world, and into which we can poke our heads and look around.

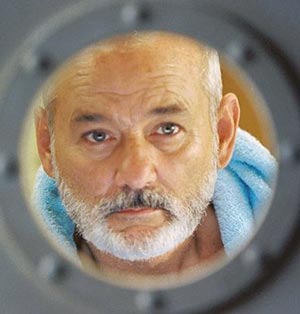

The secret world in The Life Aquatic is, in a sense, the secret world of the sea, at least as it’s explored by Steve Zissou (Murray). Sort of a low-rent Jacques Cousteau, Zissou has fallen into a personal and creative (his newest film bombs at a swank Italian film festival) following the death, by shark of an older cohort, the diver Esteban du Plantier (Seymour Cassel). The underwater explorer has resolved to salvage his career and his sense of responsibility to Esteban by filming the hunt for the shark, an exotic, never-before-seen behemoth Zissou dubs the “jaguar shark.” Despite the singularity of his prey, Zissou intends to dynamite to oblivion in an obvious act of catharsis.

Zissou himself becomes the hunted, at least allegorically. On board his rickety boat and joining his rackety crew is Ned Plimpton (Owen Wilson), a pilot for a Kentucky airline who just might be Zissou’s son (no one is sure). Another pursuer is a pregnant journalist, Jane Winslett-Richardson (Cate Blanchett), who resolutely resists Zissou’s not inconsiderable charms but who falls for Ned.

Zissou already has an ample menagerie of familial doubles and realities. His chief mate, Klaus Daimler (Willem Dafoe), displays incipient sibling rivalry when the sailor meets Ned. Meanwhile, Zissou has a rivalrous brother of a sorts himself in the person of Alistair Hennessey (Jeff Goldblum). Hennessey used to be married to Zissou’s wife, Eleanor (Anjelica Huston), who is childless, a fact that emphasizes the maternal role she plays with Zissou (and Hennessey). Finally, Zissou’s producer is the paternalistic Oseary Drakoulias (Michael Gambon).

Anderson could easily turn this mélange to farce, but it turns out to be his reflective treatment of the material (the screenplay is by Anderson and Noah Baumbach) that makes The Life Aquatic the movie it is. By forcing his cast to underplay in front of his somewhat misleadingly simple camera set-ups, Anderson is able to inflect comic material with just enough gravity to promote the audience’s empathy. He’s also able to promulgate a worldview which perceives arresting emotional problems as the stuff of everyday adjustment, an unusually mature attitude applied to a lighthearted tale (lighthearted does not always mean happy, please note).

Anderson has taken this sea saga as an opportunity expand his visual vocabulary. Naturally, a style with Anderson’s compositional emphases is going to emphasize sharp horizontal and vertical lines. The solid structures of rooms or street scenes are reinforced by rigid frame lines and relationships are sharply defined by them. In The Life Aquatic, though, Anderson’s characters find themselves again and again in or on the ocean. Here, boundaries are unknown, as verticals and horizontals are washed away by a surging endlessness. The ocean is, in effect, undelimitable, and when characters search for clearly established relationships, they find that they are unsupportable. This realization, which comes as an epiphany, is The Life Aquatic’s winning stroke.

There’s another filmmaker who makes a significant contribution. Henry Selick, the stop-motion animator director who made James and the Giant Peach and Tim Burton’s Nightmare Before Christmas, is here responsible for the fanciful creatures that stock the waves and seashores. Naturally, they include the giant jaguar shark that finally makes an appearance, but also include such delightful contributions as striped “sugar crabs.” The Life Aquatic wouldn’t be as good a film without him.