It might look like another slobbering billet doux to the delicate WASP adolescents Hollywood so loves to love (see Dead Poets Society, or most American leading men under the age of 35), but The Emperor’s Club turns out to be something else again. No, it’s not the difficult moral drama it makes itself out to be; this is a modern-day Hollywood movie, after all, so good is good, bad is bad, and never the twain do meet.

It might look like another slobbering billet doux to the delicate WASP adolescents Hollywood so loves to love (see Dead Poets Society, or most American leading men under the age of 35), but The Emperor’s Club turns out to be something else again. No, it’s not the difficult moral drama it makes itself out to be; this is a modern-day Hollywood movie, after all, so good is good, bad is bad, and never the twain do meet.

But this Michael Hoffman-directed feature is animated by a lively pugilistic passion. It unloads a haymaker aimed squarely at the jaw of George W. Bush, well-known C-student, and, according to the film, loafer, liar, class clown, cheater, by extension a duplicitous politician and by birth a snotty rich man’s spoiled son.

Where politically gun-shy Hollywood got the nerve to turn Ethan Canin’s ’80s-era short story, 'The Palace Thief' into a diatribe against the perceived moral lapses of the Bush family is ultimately a mystery. But the emergence of a presidential paradigm is always inevitable and Bush Jr.’s is actually overdue, postponed by attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon that made him hand’s off – at least for a while.

The presidential paradigm can be specifically applied in a presidential spoof (Saturday Night Live skits) or generalized portraits of a president (the not-Bill Clinton in Absolute Power, the not-George H.W. Bush in Dave). More subtly, they can infiltrate portraits of any powerful figure, comically or otherwise. During the Reagan years, for example, nearly every commercial pushing stock or banking featured a Reagan-like figure as a validating authority figure.

If the Clinton paradigm was mostly buffoonish (didn’t inhale, meaning of 'is,' oral sex), The Emperor’s Club suggests the Dubya paradigm is going to be scornful. The movie’s tone is startlingly reminiscent of the 17th century, when a Calvinist middle-class turned with fury on the excesses of a hypocritical, High-Church aristocracy.

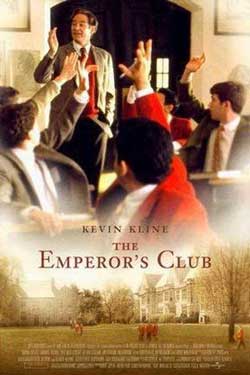

The middle-class virtues of responsibility, rectitude, civility, civic-mindedness, sexual reticence, courtesy, and restraint are embodied within William Hundert, who teaches ancient history to teenage boys at a Pennsylvania boarding school, St. Benedict’s. Played by Kevin Kline in his best Robert Donat manner, Hundert is a strict but kindly master who believes that his job is not just to drum the names of Rome’s emperors into the heads of his teenaged charges, but to mold their characters. For indeed they are, as he keeps on saying, they future leaders of government and industry.

We know this is true because the movie is told in flashback from the present day. Here we find an older Mr. Hundert delivered by helicopter to a ritzy Long Island resort, the kind where you can’t even see the golf course from the road, never mind the hotel. He’s been invited by Sedgwick Bell, a former student who represents one of Hundert’s few failures, a bright kid who never marshaled his intellectual resources or, more’s the pity, his morals, into fit shape for manhood. But, according to the invitation, Bell, who is now the head of his family’s large corporate holdings, wants to restage a competition he lost in school, in which three boys vied for the title of Mr. Julius Caesar by answering increasingly difficult questions about ancient history posed by Mr. Hundert.

And so, as he waits in his room, Mr. Hundert’s mind – and voice – drifts back to those days in 1972, when Sedgwick Bell first walked into his classroom, a cocky little disruptor and blah, blah, blah…..

The actual plot doesn’t matter much. What happens is pretty much what you’d expect to happen once Hoffman tips his hand. Naughty boy shows up; teacher takes naughty boy under his wing (teacher’s girlfriend shows up for a minute to indicate all is on the up and up); boy improves, teacher swells with pride; boy turns out to be a nasty little shit after all. This takes no more than two thirds of the movie to reveal itself, then we pop back into present day for the third act (the movie’s structured like a brick outhouse).

Here we find out that the child is father to the man. Not that the father isn’t father to the man. Young Sedgwick has a real dad, Senator Bell of West Virginia, played by Harris Yulin with as much upper-class reserve imaginable from a senator from coal-mining country. In fact, Senator Bell puts one in mind of a wealthy man (and the elder Bell is wealthy outside of his political interests) who moved south for bucks and found political fortune commensurate with his financial success; one might accuse the senator, as the Bushes have been accused, of carpet bagging. As a sop to the voters, he adopted their accents, a beau geste from on high the Bushes have been accused of making.

When young Bell graduates from St. Benedict’s, Hundert tells us in voice-over that, despite the boy’s C’s and D’s, he got into Yale thanks to family connections. Say no more. And, upon graduation, he did well in business, again thanks to family connections. Again, say no more.

The brutal stuff comes near the end, when the movie pummels the grown-up Sedgwick for grotesque moral lapses, including the tawdriest forms of cheating and emotional manipulation. In the middle of all this – and in case we’ve missed the point – Bell announces a campaign for high public office and gives a television interview in which he recites lines that could have been lifted from a Dubya stump speech.

Describing this final act really doesn’t do justice to the bile that flows off the screen. The depiction of Bell rivals that of silent screen villains brandishing the widow’s mortgage. To make things even worse, one of Hundert’s best student’s, whom the teacher short shrifted in school, has now blossomed into a veritable Ciceronian ideal, and the movie delights if setting this character’s modesty and intelligence against Bell’s grotesque egotism and dishonesty.

Fans of George W. may find it a bit hard to take, but the filmmaker’s clear and intense dislike – hatred would not be too strong a word – of his Bush stand-in is the movie’s greatest virtue. It’s not that it makes the movie more or less politically acute necessarily; it’s that it gives the film its energy and differentiates it from the steady trickle of Hollywood private boys school outings.

Hoffman has even cast the two Bells so your antenna quiver in anticipation of evil to come. Young Emile Hirsch looks, as a colleague of mine commented, like a younger version of Jack Black, ready to tear the school down. Joel Gretsch, as the grown-up, seriously dangerous Sedgwick, looks like he should be locked up on sight.

This – or perhaps these – are acid portraits and so may well stick as the paradigmatic portraits of George W. Bush. We’ll have to wait and see anyway. But if we start seeing movies featuring weasely authority figures who inherited their wealth and/or power, lounged their way through life, lie a lot, and sport phony accents, well, maybe Hoffman and company have a royalty payment due.