Bernardo Bertolucci’s films rest on the iron triangle of family, sex and politics. One of these columns may, in any given movie, be stronger than the other, but all three are ever present. So if one appears to be absent, viewers should be mindful to let their eyes drift to the edges of the frame where, sooner or later, Bertolucci will show us a door, a window through which the missing element will cast its shadow.

Bernardo Bertolucci’s films rest on the iron triangle of family, sex and politics. One of these columns may, in any given movie, be stronger than the other, but all three are ever present. So if one appears to be absent, viewers should be mindful to let their eyes drift to the edges of the frame where, sooner or later, Bertolucci will show us a door, a window through which the missing element will cast its shadow.

During The Dreamers, we never have long to wait. Set in Paris during the political upheavals of 1968, the action starts at the La Cinematheque Française just after its founder and head, Henri Langlois, has been sacked by Gaullist minister of culture, and old (former) leftist, Andre Malraux. The Cinematheque had already become a Mecca for young cinema lovers from all over Europe, while Americans where just beginning to make the pilgramage. Additionally, Langlois was already something of a national hero thanks to the way he had hidden scores of French films from the Nazis during the Occupation. His firing caused an immediate stir, then large demonstrations which provoked a violent overreaction by the French police.

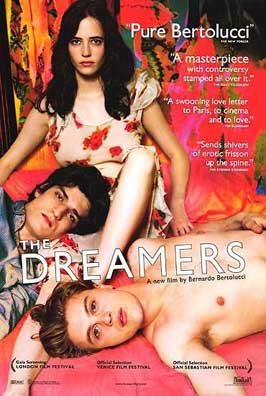

These protests and the violent reactions form the backdrop for the meeting between Matthew (Michael Pitt), an American college student, and Isabelle (Eva Green), a French student. Like Matthew, Isabelle spends as much time as she can watching movies at the Cinematheque until the government’s actions bring her into the streets. Matthew is smitten, both by Isabelle’s looks and by her free spirit, an embodiment of the era’s zeitgeist. She introduces Matthew to her non-identical twin brother Theo (Louis Garrel), and when the two discover that their new friend inhabits a closet-sized, filthy apartment, they invite him to move into their family flat, a huge, labyrinthine affair with large rooms and innumerable built-in bookcases. (While younger viewers will surely fasten on the nude young flesh soon to be on display, more veteran filmgoers will lust equally after the apartment itself.)

If Isabelle represents 1968’s liberated spirited, Theo is its more doctrinaire soul. At a dinner meant to introduce Matthew to the twin’s poet father (Robin Renucci) and English mother (Anna Chancellor), Theo tears into his father’s lack of commitment to the day’s demonstrations. He quotes the poet’s lines, once considered the height of artistic leftism, savagely, as an ironic indictment.

Theo is replicating the Malraux-Langlois (really the De Gaulle-Langlois) controversy in reverse, within the heart of his family. The father is, like Malraux, a former leftist turned bourgeois, looking inward towards career and family rather than outwards towards politics and the world. Only this time, it’s the Langlois/son figure who is on the attack, and the Malraux/father who is on the defensive.

The dinner is a good-bye repast on the eve of the parents’ departure on vacation. While they are gone, the twins and their new friend will spend a week or two naked, playing psycho-sexual games. But it’s important to recall that Bertolucci has not only set up the Cinematheque demonstrations as an opening bookend, but the dinner as a prelude.

With the parents leaving, the withdraw not only the taboos that parents and family structures impose on children. They also withdraw the political structures that have their roles in enforcing those taboos. The sudden removal of the old hierarchy leaves a political vacuum that each of the remaining players fights to fill. The most obvious contender is Theo, who tries to assume the position of the father whom, in psychoanalytic terms, he had tried to kill. Yet Theo always couches his plays for dominance in the language of liberation – the dare is always for someone to free him/herself by submitting to one stricture or another. Matthew, the American, always argues for a more democratic arrangement, though his aim is always to increase his moments alone with Isabelle. At one point in the middle of the carnal goings on, he lures Isabelle out of the flat on a “date” (the quotation marks are more or less supplied in the film).

The two men are thus always plotting for power, even if they might not be able to admit it to themselves. Isabelle is more truly anarchic. At first, she seems merely opportunistic. But opportunism is merely an outgrowth of her interest in her own pleasure and happiness. Isabelle’s response to the power vacuum is to keep it from being re-occupied. This requires her to be fluid in her response to any given situation, but ultimately she must be unreliable. Unreliability as a political position is a notion more akin to our age than to 1968; back then, Isabelle would just have been called a dirty word, as she is by both Theo and Matthew. Bertolucci makes sure, though, that we see the two young men are not disinterested commentators.

Bertolucci isn’t using the ménage a trois as a microcosm or symbol of the larger political movements of 1968. He’s examining the political structure that inheres in any relationship, especially those that affect an “apolitical” face. It’s only after seeing how each of the students tries to assert a structure in his or her own interest, that the sexual component of The Dreamers becomes coherent.

A la Jean Cocteau’s Les enfants terribles, Theo and Isabelle are in the throes of an incestuous releationship. Isabelle invites Matthew in, and while Theo acquiesces, he does so without enthusiasm. Or does he? The first sexual act the three share occurs when Theo has to masturbate in front of the other two, as part of penalty for getting the answer wrong in a favorite game of the twins, guessing a movie based on obscure clues. Matthew is shocked, but it’s not long before the twins have him disrobed on a table, indulging and performing as uninhibitedly as his hosts.

Not that this introduces a stable period in the relationship. The three personalities are way too volatile for anything close to stability to ensue. Isabelle turns out to view stability as stasis-as-death and her threats to kill everyone if their sexual games come to some sort of conclusion are taken way too lightly by her partners.

The sexual arena becomes the battleground for three contending forces: The family, politics and romance. The latter reaches an apotheosis through what is obviously Bertolucci’s favorite element, cinema, which ultimately not only provides The Dreamers’s grandest organizing element, but also the source of its true passions.

Throughout The Dreamers, Bertolucci inserts footage from other films. During the Cinematheque demonstrations, he uses old news footage of the actual demonstrations, including movie makers of the day, along with his own recreations (so we get to see slim ‘60s Jean-Pierre Leaud along with present-day fat Leaud). The clips are not chosen lightly. When Isabelle goes around her bedroom mimicking a scene from Rouben Mamoulian’s Greta Garbo classic, Queen Christina, he’s not just invoking the movie’s romanticism, but its heritage as a touchstone of repressed sexuality and so-called deviance. When he uses the Louvre racing scene from Godard’s Band a part, and has his own trio recreate it, he’s drawing a connection between his lifelong artistic project and that of an old comrade.

But there are a couple of moments that invoke cinema in two more direct ways that go to the heart of The Dreamers. The first comes when Matthew leaves the scene of the Cinematheque along with Isabelle and Theo, just prior to starting his sexual adventures with them. In a long, complex, unbroken shot, Bertolucci follows the young trio as they pass along a dark, “realistic” walkway. Then, as they turn to their right and take a stairway that leads to the bank of the Seine, they are suddenly hit by a floodlight, which casts their giant-sized shadows (images) in a big blank wall (movie screen) behind them. The image, which had been dominated by browns, yellows and blacks, suddenly erupts with color, and a vision of the three on the river bank looks like nothing so much as an MGM musical.

Here is romance heightened by the life, not “unreality,” of cinema. Similarly, when all looks bleak and hopeless after days of wanton sex in the apartment, suddenly a window shatters when a rock is thrown from the street. It’s another broad cinematic gesture that brings the three out into the student-worker demonstrations that succeeded the Cinematheque protests. As the three argue their political methods, Bertolucci stages a brilliant bit of epic cinema, a pair of tracking shots that follow the ebb and flow of demonstrators and the helmeted police ranks that attack them. More than even the MGM-style scene, it shatters the boundaries between the “real” and “cinematic.”