It’s going to be a gut-busting sprint to the DVD racks, but any truehearted film lovers out there should slip on their sneakers and beat it out to whatever local theater is still showing Walter Hill’s Undisputed. This crosspollination of a prison drama and boxing movie is more than one of the best movies of the year, which is just an accident of the calendar, after all. At age 60, Hill is entering territory cleared by the likes of Raoul Walsh, in which superficially (and, wherever possible, disreputably) routine genre material, is brilliantly illuminated and enhanced by direction.

It’s going to be a gut-busting sprint to the DVD racks, but any truehearted film lovers out there should slip on their sneakers and beat it out to whatever local theater is still showing Walter Hill’s Undisputed. This crosspollination of a prison drama and boxing movie is more than one of the best movies of the year, which is just an accident of the calendar, after all. At age 60, Hill is entering territory cleared by the likes of Raoul Walsh, in which superficially (and, wherever possible, disreputably) routine genre material, is brilliantly illuminated and enhanced by direction.

Aside from some flashbacks and maybe two cutaways, the movie is set entirely in a Mojave desert maximum-security prison set aside for murderers, rapists and other hard cases. The head guard (a welcome and, as always, taciturn Michael Rooker) has been running a series of all-comers boxing matches ever since the place opened in 1991, rotating prisoners in and out of other lock-ups when the local population ran out of challengers.

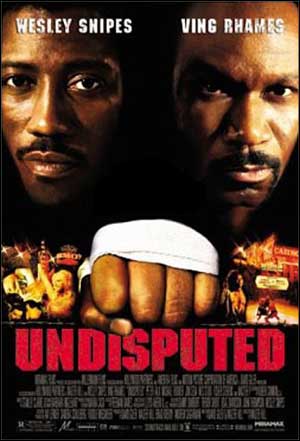

The rotation became necessary thanks to the years-long winning streak of Monroe Hutchen (Wesley Snipes), a moody, quiet man with the trimmings of one version of a classic Hill antagonist (Hill wrote the screenplay with longtime collaborator and co-producer, David Giler). In prison, Monroe barely ever speaks or reacts, even when taunted or mistreated. It’s only in the ring that he displays any violence at all, and even then his outbursts are subject to careful limitations. The only time he ever lost control, we see in flashback, was when he caught his girlfriend in the arms of another man, and beat the latter to death.

In the other corner (eventually), is George "Iceman" Chambers (Ving Rhames), the reigning heavyweight world champion, just convicted of raping a young woman. Hill plays up a soupcon of ambivalence over whether the woman has truly been sexually assaulted or, as an unrepentant and generally enraged Chambers insists, just an opportunist. As it turns out, though, that’s because the director is waiting to establish Chambers as capable of rape, before acknowledging that he’s actually guilty of it.

Hill introduces this complication early in the movie, during a blistering introductory set-up that shows off his editing skills at their best. Using a mixture of film, video, video and aural overlays, schematic drawings, Hill sucks us into the action of what appear to be two towering men.

Interestingly, though he returns to Monroe with dutiful regularity, it’s the Iceman (though he’s the least cool Iceman ever), who captures Hill’s interest and whose dynamic shifts in status compose the movie’s core. The champion is sure that his lawyer is going to spring him in a matter of months if not weeks, and that in the meantime, all he has to do is display his X-X-L machismo to get by.

At first it works. The prison population is as star struck as any other, and is delighted to see the Iceman bitch slap Monroe once the champ finds out about the prison boxing program. But as the Iceman’s days becomes weeks and then months, he becomes just another prisoners, and his efforts to insist on his superiority come to seem merely bombastic.

As he often does, Hill relies on lens selection and editing to convey Iceman’s predicament. When he arrives in prison, long lenses (Hill must be shooting his scenes from hundreds of feet away), isolate the apparently gigantic boxer from the general population even as it swarms around him. Not only does he claim the shallow focal point left to him, but his size and scale are distorted in his favor. Similarly, in these early scenes, whenever Hill cross-cuts between Iceman and another character, the director usually makes sure that Iceman’s body and face dominate the frame, while on the reverse angle, those talking with the Iceman are left with emptier space around them, as if they are isolated and alone. There’s a scene in which Iceman humiliates a character named Rat Boy (Fisher Stevens), in which Hill brings both techniques into play.

As the movie goes on, and Iceman’s position becomes more precarious and the prison population more hostile, Hill’s technique shifts. The lenses become shorter, and so Iceman’s space less privileged. Now he becomes more hemmed in whether he’s just standing or sitting (lens work), or we’re seeing cross-cutting between him and others in the prison. Again, one scene sums up the change, this one in the prison cafeteria, which concludes with a near riot precipitated by the Iceman’s near indifference to the other prisoners.

Dramatically, as the boxing match nears, Iceman’s personality is shifting, becoming more stripped down and more like Monroe’s. In Hill’s world, this makes him a more appropriate opponent for Monroe. Thus, the world – Hill’s world – is brought into balance and a climax can be undertaken.

Undisputed presents a chance to see an auteurist classic the first time around. Don’t blow it just because its distributor did.