Eye gougings, bodies being ripped and shredded by chains topped with iron claws, and blood whistling from rows of knife wounds are not likely to lure the filmgoer in search of "cinema," especially if he or she expects those outrages to be accompanied by poorly dubbed sound, streaky color, and inept direction.

Martial-arts movies are victims of the box-office boom that erupted 12 years ago when the success of Bruce Lee kung fu movies (such as Fists of Fury) had every schlockmeister from Hollywood to Hong Kong rushing to get six-day wonders in front of the cameras. The resulting production glut featured bug-budget America-Hong Kong co-productions (Warner. Bros's Enter the Dragon, the Bruce Lee starrer that, thanks to. Warner's distribution setup is still the genre's box-office champ) and pale all-USA imitators (anything starring Chuck Norris). There were even sleazy English/German/Chinese productions like the bizarre Seven Sisters vs. the Vampires, which mixed new footage of seven women delivering groin kicks to huge puppets with old footage of English horror star Peter Cushing gloating over a woman in bondage. These hybrids swamped the more idiosyncratic, albeit commercial, products of Hong Kong studios like the Shaw Brothers or Johnny Mak Productions. Now that the kung fu flood has ebbed, these all-Oriental films are getting some screen time at the Pagoda Cinema Complex on Washington Street, which advertises "the only English language Kung Fu films in Boston," a new double bill every week.

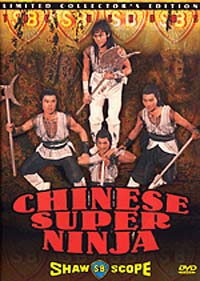

The Superninjas which came and went as part of a Pagoda double bill and which typifies Pagoda fare, is a product of the Shaw Brothers' movie factory – the Hong Kong equivalent to MGM. Now undergoing a revival under Mona Pong, Superninjas' producer, Shaw Brothers movies bear the mark of the tension created by two conflicting impulses; do it right, but do it quick. Superninjas features striking exterior sets executed in the studio, notably a pond hemmed in by reeds and forded by a wooden bridge that leads to rolling hills on each side, with a delicately painted horizon in hues of blue and orange.

However, director Chang Cheh drenches it all in bright, even light, which makes easier to move the camera into the different setups required by the sprawling martial-arts encounters but that eliminates all possibility of using lighting for mood.

Since kung fu audiences are gluttons for somebody's punishment, the more slashing and flailing-away, the better. No dawdling in the shooting or the viewing. Superninjas is the kind of martial-arts movie that features more armed fighting than fist fighting, more blood and fewer bruises. Set in medieval China, it opens with a 20-man tag-team match as two martial-arts schools face off. The white-clad champions of Mr. Li win all the way, even when their rival produces a mercenary Japanese ninja as his ultimate warrior. The shame of this defeat drives the ninja to ritual suicide, but he vows a friend, the baddest ninja of all, will come to avenge him. Of course, the ninja makes his vow after he has plunged his sword into his stomach, ripped it across his body, and then freed it. This suicide sets the plot in motion and tips us off to the movie’s aims. Throughout, violent death leads to revenge, rebirth, and reconstitution. The superninja comes to avenge his friend and wipes out Li's 10 champions. Li's school counterattacks, and is wiped out in turn. A warrior survives to avenge his brothers, and the superninja gets it. In the end, a new trio of fighters is left alone with a new master.

Superninjas swirls through it characters like a brush fire - just when we think we've discovered the movie's nominal hero, he's offed. The persistent onslaught of violent death accompanied by gallons of spraying blood (one warrior loses a fight when he trips over his own dangling entrails) eventually serves to distance us from the violence; there's just too much of it to take seriously. And the leisurely details of the deaths transform them into rituals that are keys to the films underlying cycles. The movie ever goes so far as to say that the Japanese ninja's arts originated in ancient China, only to be forgotten and transported back to Japan, and that the Japanese ninja's death will lead to a revival of his arts in China.

The terse dialogue, the breathless rush from fight to fight, and the body count of heroes gives this movies and others like it a jagged, flashing, comic-book urgency. Although director Chang relies on reverse motion to execute several spectacular leaps, his exuberance suffuses even the obvious fakery. Watching Superninjas is more fun than reading Conan comics - or seeing the movie, for that matter.