If he’s proven nothing else with his six Star Wars movies, writer-producer-director-uberlord George Lucas has demonstrated that he is one of the most persnickety filmmakers of all time. With the three most recent of the movies (prequels to the first three, as if you didn’t know), Lucas has nailed down every loose plot point from the first three with the finality of a mortician hammering shut a coffin. To keep the movies up to date technically, he has revised the effects in the first three not once, but twice.

If he’s proven nothing else with his six Star Wars movies, writer-producer-director-uberlord George Lucas has demonstrated that he is one of the most persnickety filmmakers of all time. With the three most recent of the movies (prequels to the first three, as if you didn’t know), Lucas has nailed down every loose plot point from the first three with the finality of a mortician hammering shut a coffin. To keep the movies up to date technically, he has revised the effects in the first three not once, but twice.

It’s an irony of no little humor that all this artistic control has been lavished on an enterprise that proclaims that our destinies are written in the stars. Clearly, Lucas has left little to the stars – either the universe’s or Hollywood’s. Looking at it that way, the six films begin to look like the expression of Lucas’s neurotic fear that individual ambition and initiative aren’t sufficient to a successful navigation of life’s rapids, that the Fates can upset even the most precisely laid plans.

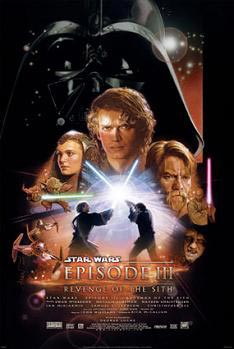

For those of us who prefer a little spontaneity in art, though, there is a glimmer of an idea that may have slipped unobtrusively into the Star Wars movies, and particularly into the meticulously titled Star Wars: Episode III Revenge of the Sith.

First, though, what kind of movie is Revenge of the Sith? A lot better than its immediate predecessors, that’s for sure. Much of the “mythic” gobbledygook has been excised, leaving a relatively lean work in its wake. That’s “relatively” lean, though.

The plot, in its essence, marks the break between apprentice – more like a journeyman, actually – Jedi Knight Anakin Skywalker (a truly terrible Hayden Christensen) and his mentor, Jedi Knight Obi-Wan Kenobi (light and lively Ewan McGregor). The break between the two is fomented by the head of the prevailing space federation, Chancellor Palpatine (Ian McDiarmid, who deserves a great deal of credit for hitting the exact combination of emotional credibility and bigger-than-life villainy). Far from being defender of his democratic republic, though, Palpatine is a plotting, evil Sith Lord who plans to declare himself emperor. Sith Lords feed off the same mystical Force as the Jedi Knights, but from its dark side. Palpatine implements his seduction of Anakin by using this most powerful aspect of the Force as a lure, a strategy which, as we know from the other Star Wars movies, is successful, with young, innocent Anakin morphing into the more-evil-than-evil Darth Vader.

There’s a bit more, but that’s the gist of it and, in any case, if you’re reading this, you probably know the story in exhaustive detail anyway. This time out, it’s a good thing that the plot is so relatively simple, since Lucas has weighed down Revenge of the Sith with an enormous number of high-tech battles. Those who don’t make such razzle-dazzle their main cinematic meal probably have their appetites sated by the movie’s opening and closing set-tos. The first, which opens with a single shot that sings through space and from long-shot to close-up and what-have-you, is a surely brilliant display of modern pyrotechnics. Its cogent narratively too, depicting the exuberant friendliness between Anakin and Obi-wan as they rescue Palpatine from a rebellious army. The last – or nearly the last, aside from some brief action bits – is the climactic showdown between the two former comrades.

There’s a lot more where they came from, though, all of it excused by an ongoing rebellion against the Republic by the so-called Separatist Alliance and its android army. Lucas means for the rebellion to play a large part in Palpatine’s conniving and Anakin’s apostasy, but even so, this excess of action is justified by nothing so much as the excess itself. Lucas is displaying that he can do more better in this field than anyone else can.

Fun for its own sake shouldn’t need any justification, especially in a pop entertainment such as Star Wars. But the large-scale battles and duels in Star Wars are fun only up to a point. Beyond that, they feel insistent, compulsive. Their superficial pleasures begin to shrink next to the strained urge to excel that seems to underlie them.

In any case, Palpatine’s eagerness to defeat the Alliance with unchecked ferocity, in mark contrast to the Jedi Council’s less bloodthirsty stance, attracts Anakin, who wants to avenge the crimes perpetrated by the rebels. Psychologically, though, it’s probably the least of three motivations.

The young warrior is also worried about the children he expects to have with his beloved, Padmé Amidala (Natalie Portman, better than in the earlier films), a queen on her home planet and a senator in the Republic’s assembly. The two have been secretly married and Anakin has been troubled by dream visions of her dying in childbirth. He becomes increasingly preoccupied with averting this personal disaster, a weakness Palpatine exploits with the promise that the dark side of the Force will avert it.

It’s the third motivation that, though it seems the most trivial, is the most intriguing. Anakin has resented the limits the Jedi knights have been putting on his power; he is, after all, supposed to be the Chosen One, an epochal personage who is going to balance the metaphysical powers of the universe (or whatever). Yet his superiors keep treating this adolescent as if he was just exactly that, a mere adolescent. This resentment finally boils over when Palpatine gets Anakin appointed to a reluctant Jedi Council but the sitting members refuse to grant him all the usual honors. This, as much as their wartime caution and careful rationing of their potentially great powers, marks them as morally suspect to Anakin. For these men won’t give him his due.

This is simple adolescent moral narcissism, an obnoxious period we all pass through. Simply (simplistically?) put, this phenomenon occurs at an age when a kid develops a distinct and necessary sense of morality. Unfortunately, this happens at an earlier age than that when we fully refine our sense of empathy. Our sense of morality and self-centeredness get all mixed up so, when as happens to Anakin, people don’t respond to our requirements, it’s not just a lack of perception on their part, but a failure of morality. To put it familiarly, they’re just not being fair.

Emotionally, this narcissism looms as Anakin’s primary resentment. It may be Christensen’s callow performance, but the potential death of his wife doesn’t seem to strike him with the same sense of grievance. It’s not that he doesn’t feel bad about Padmé’s risk. But – and this is where it simply may be a matter of bad acting – to all appearances, the boy reacts much more viscerally to the perceived insult of the council.

Once you become alert to this side of Revenge of the Sith, then the whole Star Wars project begins to seem like a study of adolescent narcissism. Luke Sywalker, after all, deeply resents how the aged Obi-Wan (in the first film) and Yoda (in the second) keep putting limits on how much of his innate power he’s allowed to exercise. Luke, though, manages to develop enough empathy to resist the temptation to go over to the Dark Side by the time Darth Vader makes his case.

This is where the spark of spontaneity lights up some of the murk surrounding Star Wars. The movies have always been vague on exactly what the Force is, aside from being a potentially unifying element of the universe. The lack of clarity wasn’t helped by the influence that the semi-scholarly Joseph Campbell, and his all-myths-are-the-same-myth theorizing, had on Lucas, at least when he was making the original three movies. Mystic vapors clouded the combination of facile psychology (“Luke, I am your father”) and heroic quest that loosely cohabitated at the Force’s core.

Teenaged self-centeredness and its antithesis, empathy, might sound like relatively puny particulars to represent the contending sides of the Force, but at least they’re something specific. Anyway, since when is empathy insignificant? Maybe the heroic quest isn’t a search for ultimate meaning, but simply for other people. Just because that’s a conclusion that the histrionic Lucas seems to have found in spite of himself doesn’t make it any less relevant to his grandiose opus.