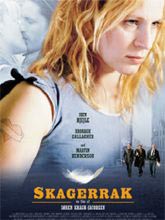

In his 1999 film, Mifune, Danish filmmaker Soren Kragh-Jacobsen didn’t so much employ the techniques of the Dogme filmmaking system so much as surmount them with a blend of rough comedy, unbridled sexuality, and a profound faith in romance. Kragh-Jacobsen’s latest, the English-language Skagerrak, demonstrates those attributes represent the core values of a director who, freed from artificial restrictions, turns out to have a deft touch with an ensemble cast and a masterful control of tone.

In his 1999 film, Mifune, Danish filmmaker Soren Kragh-Jacobsen didn’t so much employ the techniques of the Dogme filmmaking system so much as surmount them with a blend of rough comedy, unbridled sexuality, and a profound faith in romance. Kragh-Jacobsen’s latest, the English-language Skagerrak, demonstrates those attributes represent the core values of a director who, freed from artificial restrictions, turns out to have a deft touch with an ensemble cast and a masterful control of tone.

It’s difficult for an American critic to assess this latest work in the context of the 56-year-old’s career, since he’s been making features since 1977 and only Mifune was released theatrically released in the U.S. But Skagerrak is a modern rarity, the putatively light romantic comedy built around an apparently hackneyed plot, whose considerable surface pleasures only barely mask a serious preoccupation with love’s transformational power.

That latter concept has been cheapened lately by a dozen Hollywood outings that tie that transformation to sudden wealth or improbable steps up the class ladder (The Wedding Planner, for example). It’s a measure of Kragh-Jacobsen’s film’s relative complexity that one of its minor accomplishments is a refutation of wealth; contrarily, it asserts money is more often an impediment to love that a help.

Much more satisfying, though, is the way it slips from one depiction of love to another. It begins with what is perhaps its purest and most touching example, the friendship between two single working women in their late 20s, Danish Marie (Iben Hjejle, of Mifune and Hi Fidelity) and Irish Sophie (Bronagh Gallagher, at 30 a veteran actress in her first and much deserved leading role).

The pair has just spent months working as cleaning women on a North Sea oil platform and now they’ve landed in a Scottish port with plans to blow a thick role of saved pay on fun and relaxation. Fun includes drinking and some lusty encounters with whatever men they encounter, a binge they expect to share just the way a couple of male buddies would. But just as a couple of sailors might find themselves in an unexpected hole after a first night in port, so Marie and Sophie find themselves similarly gutted the morning after.

Kragh-Jacobsen co-wrote the movie with Anders Thomas Jensen and the story they’ve chosen to follow, in strictly narrative terms, has the two women going from bad luck to tragedy. When Marie tries to get back on her feet on her own, it is in a way that sounds like routine soap opera, as does her escape from ensuing complications.

But the film’s tone is so distinguished that it may never cross the viewer’s mind that the material itself is familiar stuff. The friendship between Marie and Sophie energizes the entire film, even when only one of them is physically present, so that there is an emotional aura constantly highlighting events.

Moreover, much of the film is hilarious. Around its midpoint, the action shifts to Glasgow and a garage run by a trio of eccentrics played by Ewen Bremner, Simon McBurney, and Gary Lewis. Not only are their characterizations funny individually, but the comic interplay is integrated in raucous harmony.

Less colorful, perhaps, are James Cosmo, Scott Handy, and Helen Baxendale as a country squire, his son and daughter-in-law. These play, if not the villains of the piece, then the more ignoble personages (and not coincidentally, the richest). But Kragh-Jacobsen refuses to dismiss them out of hand and by the time the movie is done with them, he has allowed them to reveal themselves as victims of love in their own right. If they had been poor, we might conclude if we thought about it, they’d have been better behaved. This requires a great subtlety of performance and Baxendale in particular comes through with it.

Kragh-Jacobsen has directed Skagerrak in a classical style sometimes called "invisible." That is, it eschews the authorial flamboyance of, say, Dogme. But the director’s employment of light is as careful and expert as his handling of the cast. His film ends up a marvelous mixture of accessibility and insight.