Contemporary graphic novels and traditional comic books form a rough analogy to second-generation immigrants and their parents: Ostentatious spending replaces enforced frugality, as does an impulse to pump up the social status of modest origins. This sort of social climbing is not only a dubious activity to start with but an exemplary substitution of fashion for style. The appropriation of comic book forms by filmmakers stretches out the analogy to include the third generation’s embrace of its grandparents’ ethnic roots – except of course, those roots have not only been radically retailored to fit the new “owners,” but represent a self-defeating quest for an illusory authenticity.

Contemporary graphic novels and traditional comic books form a rough analogy to second-generation immigrants and their parents: Ostentatious spending replaces enforced frugality, as does an impulse to pump up the social status of modest origins. This sort of social climbing is not only a dubious activity to start with but an exemplary substitution of fashion for style. The appropriation of comic book forms by filmmakers stretches out the analogy to include the third generation’s embrace of its grandparents’ ethnic roots – except of course, those roots have not only been radically retailored to fit the new “owners,” but represent a self-defeating quest for an illusory authenticity.

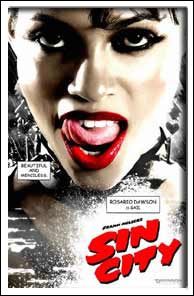

Welcome, then, to Sin City, the adaptation of Frank Miller’s graphic novel, directed by Robert Rodriguez and Miller himself. Based on what the movie looks like, I’d say Miller’s work is heavily indebted to Will Eisner’s The Spirit graphically and the most hardboiled crime of crime novels, perhaps those of James Hadley Chase, for character and sadism. It’s a black, white and gray world, full of large, looming buildings, limbed woods, clawing shadows and massed compositions. It’s always night and light is a matter of sudden shafts which emerge to illuminate an act of violence. Flamboyantly, the movie introduces bits and pieces of color, usually scarlet to vivify splashes of blood, but also yellow for the occasionally blonde and blue or green for eyes.

The dialogue follows the same pattern: Guns are always “rods,” a man with a heart condition has a “bum ticker,” and the women are “dames” – that is, when they’re not “hookers” or “whores.”

That’s not to say this is all bad. To give in to the banter, you could say the movie looks swell, a bizarre combination of live-action and animation that breeds its own dreadful emotions. Miller’s dialogue can be quite good in its deliberate quaintness; telling us in voice-over (which coats the entire soundtrack), that he’s going to kill someone, one of the characters says, “I’m going to give him the hard goodbye.” Not bad and fairly typical.

Sin City falls down, though, when it comes to plot and emotion. Framing bookends aside, the movie is constituted out of three, or three-and-a-half, different vignettes.

The first, and best, features Bruce Willis as a Ba(sin) City police detective on his last shift who has sworn to use his last minutes on the job to bring a child molester-murderer to justice (justice being a violent end rather than a trial). The second is the most inventive, but marks the beginning of the movie’s steady descent into narrative futzing around. In it, Mickey Rourke stars as a leonine tough guy who not only looks part animal, but has strength bordering on the superhuman. Forced into social isolation by his looks and brutally sadistic by nature, he seeks out the killer of the only good-looking woman who has been sweet to him. Finally, the final, almost hopelessly dragged-out story nominally stars Clive Owen as an underworld figure who goes toe-to-toe with Benicio Del Toro and, later, helps out a gang of prostitutes headed by Rosario Dawson. One of these tales then receives further treatment in a concluding chapter.

While you could say the men come in at least two varieties – bloodied white knights and bloody knaves – the women are basically prostitutes, with a waitress or low-level criminal thrown in here and there. Their professions aside, the women are subjected by Rodriguez and Miller to scenes of undress, with the camera frequently reverting to buttock’s level (variations on the thong abound).

While you could say the men come in at least two varieties – bloodied white knights and bloody knaves – the women are basically prostitutes, with a waitress or low-level criminal thrown in here and there. Their professions aside, the women are subjected by Rodriguez and Miller to scenes of undress, with the camera frequently reverting to buttock’s level (variations on the thong abound).

The portrait of women gets an insistent justification from Sin City’s evocation of hardboiled fiction and comic books. It’s not us, the filmmakers implicitly say, it’s the world we’re paying tribute to. What’s more, this argument goes, the hookers are tough, self-employed types who more than take care of any troublemakers who pass through their territory. Well, yes, that’s all true, but a close-up of someone’s tush is still a close-up of a tush. Certainly there isn’t a female character as filled-out as Willis’s cop or as inventively conceived as Rourke’s bizarre creation.

More than the sex, it’s the violence that will strike viewers. In one bit -- among the most violent but not too exceptional for all that – a young man is tied to a tree with his arms and legs cut off, then eaten by a dog. That the character is a cannibal is supposed to make the extreme violence all right, but, again, the act has a resonance of its own beyond any narrative justification. A tush is a tush.

Even the movie’s technique emphasizes the brutality. When one character gets punched in the mouth, the blood shoots from his mouth in a blizzard of bright red, not just vivid against the gray, but shocking, too.

Sadism or sado-masochism (it depends on who you’re rooting for in a particular scene as to which is predominant) is largely titillating for the participants, but has a built-in obsolescence factor for viewers: Yeah, he’s bleeding; who isn’t? The proof of it fast-fading durability is easily measured by the impact Bruce Willis and, to a somewhat lesser extent, Mickey Rourke have on the movie. Willis especially invests his aging detective with a plausible weariness that suggests a human being lurking behind the self-conscious construct. When he talks about growing old, he suggests a quality – the passage of time – that transcends the action immediately on view. It’s rare indeed that any of the figures in Sin City outgrow their graphic conception.

Sin City’s emotional life is rarely filtered through the characters. Rather, the unrelenting violence erupts almost directly from the hand of Rodriguez and Miller. You could say the struggle is Oedipal, in that the big crooks are authority figures and the women are all sexually available. But that implies a level of artistic processing that rarely take place.

Since our mature personalities are shaped by the rages of our infancy, it would be a bit unsophisticated to object to art formed by the residue of those ancient impulses. The problem with Sin City, though, is that all that vestigial anger isn’t transformed, sublimated or even elaborated so much as it is just decorated. A two-hour rant, the movie suffers the fate of all witnessed tantrums: Its ferocity gives way to boredom and finally to exhaustion.