Pray to high heaven that Jack Black never falls into the hands of a personal trainer, because right now the performer is the U.S.’s prime embodiment of the light-footed funny fat man. True, Black is more plump than obese, nearly a shadow of Jackie Gleason or Zero Mostel. But he plays up his jelly belly with true panache, deploying a seemingly endless array of walks, prances, leaps and jumps that simultaneously emphasize his mass and defy it.

Pray to high heaven that Jack Black never falls into the hands of a personal trainer, because right now the performer is the U.S.’s prime embodiment of the light-footed funny fat man. True, Black is more plump than obese, nearly a shadow of Jackie Gleason or Zero Mostel. But he plays up his jelly belly with true panache, deploying a seemingly endless array of walks, prances, leaps and jumps that simultaneously emphasize his mass and defy it.

Black exceeds Gleason and matches Mostel when it comes to facial manipulation. Blessed with eyebrows that could reproduce hieroglyphics, the actor-musician gets much more out of them (or his rubbery mouth) than the torrents of laughs that can drown an audience in mirth. As did Mostel, Black possesses a mad stare that drills through whatever he’s looking at, whether friend or foe (or audience). He’s a man possessed, even if what possesses him is ultimately his own idea of himself. His body flies through the air, changes rhythms, bursts into song, or crouches in stillness because it can hardly contain a huge spirit bursting to fill a world that doesn’t recognize its greatness.

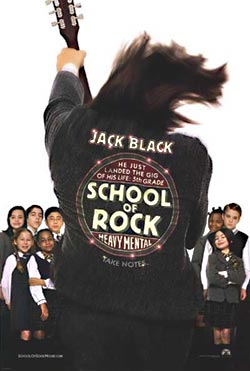

The Farelly Brothers, who tried to craft a vehicle for Black in the disastrous Shallow Hal, missed the point of Black’s personality altogether. But director Richard Linklater and screenwriter Mike White have zeroed in on it exactly. School of Rock is as perfect a vehicle for Black as could possible be imagined.

Playing an unsuccessful rock and roll guitarist who has been kicked out of his own band and is about to be kicked out of his own apartment, Black starts out from a perfect position: The visionary convinced of his own righteousness in a world where he’s taken for a loser. His character, Dewey Finn, desperately needs followers who will prop up his ego, help him avenge himself on his detractors, and ultimately set the world aright – that is, put Dewey on top.

Those followers end up being fifth-graders at a posh private school where Dewey takes a job as a substitute teacher under false pretenses (the headmistress believes that Dewey is his roommate, legit sub Ned Schneebly). After the humiliated rocker hears his charges playing their instruments in a music class, he throws their classical sheet music away and turns his classroom into, well, you know the movie’s title.

School of Rock has plenty of funny situations and some jokes, but mostly it has Black. It’s the performer who is funny, not anything put in his way. He plays well enough off the children, and very well with Joan Cusack, who undertakes the role of the headmistress with her customary and welcome eccentricity (would calling her the American Joyce Grenfell ring a bell with anyone out there?). Screenwriter White plays the real Ned and stand-up comedian Sarah Silverman plays Ned’s nagging girlfriend, though why remains unclear; perhaps there were no actual actors in town on the day auditions were held.

But Black’s true costar is his own body. It’s not that he’s at war with it. Truthfully, his mind and body are at one in terms of their aims. There are moments, though, when each are taking different paths to the same conclusion. Especially when he’s first introducing his 10-yewar-old bandmates to the history of rock and roll, his mind, tongue and body don’t do double-takes so much as triple-twists.

Lest you think this is all you get, School of Rock is also a legitimate Linklater film. When he’s been at the top of his game (Dazed and Confused, Before Sunrise, Waking Life), Linklater sets his movies at moments of union and/or celebration that coincide with departure and loss. He tried raising this undercurrent to the level of an overt theme once, in The Newton Boys, and came up with his one true stinker. But without it, his films tend to drift (SubUrbia). So he’s a filmmaker who treads a tightrope every time he walks out to his camera.

You may not notice it under the good-humored raucousness of School of Rock, but Linklater performs his balancing act very well indeed here. Dewey’s "grown-up" friends are constantly telling him, with some good reason, that it’s time for him to give up his diminishing dream of rock and roll success and get a "real" job, advice Dewey refuses to take. When Dewey bonds with his kids (and it’s a touching bond, for all the laughs), he finally does get to realize those dreams on a stage in front of appreciative fans (this is hardly giving away a surprise, since the end of the film is obvious from the first shot).

But Dewey has also given a lot away by that point. He’s not performing his own song, he’s performing one written by one of the kids. He’s not wearing his own clothes, he’s wearing a school uniform. And it’s very unlikely that his moment of glory is going to lead to any more. With happy discretion, Linklater brings down the curtain, but sensitive viewers will note that he does so with no suggestion of success to come.

Luckily, while that might apply to Dewey, it certainly doesn’t apply to Black. School of Rock, after many promises and one big false start, finally marks the entrance of a major comic talent. Thank goodness.