I think I figured out what Pope John Paul II really said about Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ. Reports from the film’s most ardent supporters continue to insist that the pontiff exclaimed, “It is as it was” after seeing Gibson’s cinematic depiction of 12 hours of Good Friday. These words are supposedly an endorsement that the film is factual (yeah, and Braveheart was, too). But I think there was a problem translating an idiomatic phrase the pope must have used. To my mind, His Holiness, in an effort to remain politely noncommittal, must have said some version of “It is what it is.”

I think I figured out what Pope John Paul II really said about Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ. Reports from the film’s most ardent supporters continue to insist that the pontiff exclaimed, “It is as it was” after seeing Gibson’s cinematic depiction of 12 hours of Good Friday. These words are supposedly an endorsement that the film is factual (yeah, and Braveheart was, too). But I think there was a problem translating an idiomatic phrase the pope must have used. To my mind, His Holiness, in an effort to remain politely noncommittal, must have said some version of “It is what it is.”

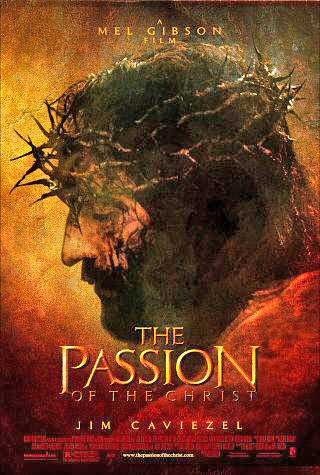

Seriously, folks, Mel Gibson rides his mile-wide sado-masochistic streak into the heart of the Passion story and, with The Passion of the Christ, emerges with a propagandistic, comic-strip version of the death of Jesus Christ.

To deal quickly with the propaganda: Since not every Jewish character has a large nose, sunken eyes, or skulks around in black robes while conspiring against a barely Semitic-looking Jesus and handing out blood money to Judas, you may want to excuse it from charges of anti-Semitism. Personally, I figure that the half dozen or dozen such characters that slither through the movie looking such and doing such is enough to make the charge stick. Sister Marie Bernadette, who could make 4th graders cry with her narration of the events of Good Friday, never conjured up Pharisees remotely like the creepy ghouls on display in Gibson’s movie. In her version – which was the Gospels’ version, by the way – the Pharisees were a nasty bunch, but a small non-representative one at that. Yes, some of the Jewish people (never “Jews,” by the way, always the “Jewish people”) wanted Jesus out of the way because he threatened their power. Of course, you have to have power for it to be threatened, so that automatically limited the number of people concerned in the Roman-occupied territory. At any rate, Christ freely accepted his death, so there is no reason beyond directorial preference to have these Werner Krauss look-alikes on screen at all.

As for the rest of the film, at first it’s not entirely clear what Gibson’s purpose is for a while. He starts things off in the Garden of Gethsemane, where Jesus agonized over the suffering he was about to endure while three of his Apostles slept nearby. To emphasize Christ’s conflict, Gibson inserts an androgynous, cowled devil who skulks (there is an enormous amount of skulking in Gibson’s Passion, perhaps the most skulking in any film since the silent era) around the savior, sending a snake out from under his black robe. The scene is dark and cut in a such a way as to keep the viewer a bit off center. It’s almost as if Gibson were shooting for a mystical treatment, taking his lead from the Gospel of St. John.

But then we come to those toxic caricatures of Caiphas and the High Priests and a slow-motion shot of the bag of 30 pieces of silver being tossed to Judas. Here, Gibson is led less by the Gospels than by such discredited pageants as the Passion Play at Oberammagau, which was told to tone down its depictions of Jewish characters by the Catholic Church hierarchy.

Finally, though, when we get to point where Christ is arrested by the Temple Guard, brought before the Roman governor Pontius Pilate, and scourged at the stake, it suddenly becomes absolutely clear what Gibson is doing: He’s illustrating the 14 Stations of the Cross. In Catholic churches, the Stations are representations of Christ’s suffering and death, beginning with number one, “Jesus is condemned to die,” culminating in no. 12, “Jesus dies on the cross,” and ending with “Jesus is laid in the tomb.” It also has, among others, “Simon helps Jesus carry his cross,” “Veronica helps Jesus wipe his face,” and three occasions when “Jesus falls.”

During Fridays in Lent, the 40 days before Palm Sunday – 40 days Jesus spent in the desert – it is common for Catholics to go from station to station saying special prayers. Despite the pictures most churches boast at the stations, pictures, it’s a largely literal experience, based on the prayers and responses.

Despite excessive use of slow motion, lingering shots on nails driven through hands (more on that later), and Caleb Deschanel’s overlit cinematography, Gibson’s Passion is also largely a literal-minded experience. What we see on screen isn’t meant to spark a spontaneous reaction – the shock of the new within the familiar – but just to remind us of something we already know. Ah, yes, here Jesus is crowned with thorns, here Pilate washes his hands. All the meaning is external. None of it arises from within the drama of divine sacrifice.

What Gibson does bring to bear on the material is his masochistic imagination and, to a lesser extent, his homosexual panic. Every physical travail to which Christ was subjected is lovingly enhanced with every device Gibson can imagine. The scourging is a case in point. Christ is tied to a post and whipped with rods by two Roman soldiers who, with their armor and bald heads, look very fetishistic. When his back is covered with welts, the soldiers switch to cats-‘o-nine-tails with hooks on the end. Gibson makes sure we not only see the hooks catch the flesh and tear it, but get caught so that a soldier has to give an extra tug and thus pull an extra hunk of flesh out of Jesus’s back.

Gibson has tried to immunize himself against charges of sado-masochistic self-indulgence by saying that he’s made the film so violent so that audiences will understand just how great Christ’s sacrifice was. This is, first of all, the height of arrogance. Two millennia of Christianity suggests that untold millions have had little or no trouble imagining the enormousness of Christ’s sacrifice without the help of blood squibs and special makeup effects. Gibson’s claim to show the truth of it all is the worst kind of Barnum-ism, the substitution of sensationalism for truth.

More to the point, this isn’t about Christ, it’s about Gibson. The Man Without a Face and Braveheart took essentially the same tack to tell analogous tales of abused saviors. The ripped and pierced flesh of Gibson’s Passion is an inevitable escalation that began with the scarred face of the former film and the conventional, if pervasive and enthusiastic, violence of the latter.

Similarly, in his Passion Gibson gives us a mincing, lisping King Herod, who isn’t an escalation so much as a repetition of the cowardly gay princes of Braveheart. Both cases, though, present embodiments of the false charges of pederasty that lay behind the drama of Man Without a Face.

sIn light of the last two points, it’s interesting that, in the film’s press note, Gibson says that the Mannerist painter Caravaggio provided the inspiration for his Passion’s visual style. It’s an interesting statement considering that there’s not a frame in the film that recalls the great artist who, among other things, felt himself unappreciated in his time.