In the past, Todd Solondz has gone to town with characters who desperately crave happiness but who start from such a deficit that maybe the best they can hope for is a kind of equilibrium between depression (or worse) and, well, if not happiness, than anti-depression (or anti-worse). The work that seemed to hit home hardest was 1995’s Welcome to the Dollhouse, the story of a young misfit (brilliantly embodied by Heather Matarazzo) who suffered from familial indifference and junior-high-school cruelty. The character, Dawn Wiener, was in extremis as far as social isolation went, but people are so convinced that they were isolated when they were Dawn’s age, that it was easy to identify with her.

In the past, Todd Solondz has gone to town with characters who desperately crave happiness but who start from such a deficit that maybe the best they can hope for is a kind of equilibrium between depression (or worse) and, well, if not happiness, than anti-depression (or anti-worse). The work that seemed to hit home hardest was 1995’s Welcome to the Dollhouse, the story of a young misfit (brilliantly embodied by Heather Matarazzo) who suffered from familial indifference and junior-high-school cruelty. The character, Dawn Wiener, was in extremis as far as social isolation went, but people are so convinced that they were isolated when they were Dawn’s age, that it was easy to identify with her.

In Happiness, Solondz moved on to a wider range of characters and difficulties which deliberately eschewed, in all but one case, the identification process. The film’s conclusions weren’t much different from Welcome’s, but the variations on the tune were as – how to put it? – just as cacophonously melodious.

With Storytelling, a feature-length film made composed of a short and featurette, Solondz peaked with his material. In the short, he depicted a poisonous interaction between a creative writing course student and her university professor that, brilliantly at tines, aired out the darker psychological complexities of student-teacher relationships. But the featurette, built around a Solondz stand-in (he has denied it’s a stand-in) who tries to make a documentary about a high school student who made the previous generation’s slackers look like worker ants.

With that work, Solondz went camp, making fun of middle-class mores less with a cleaver than with a butter knife. You can make a case that a person’s table manners are more subtly revealing of personality and status than, say, a murder, but Solondz’s film wavered between aiming at that complex phenomenon and settling for cheap send-ups.

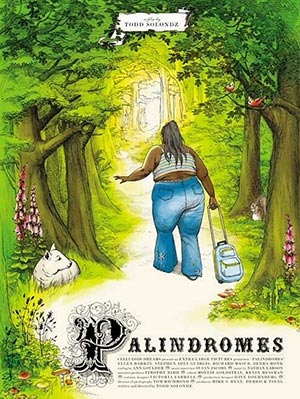

There’s little evidence that the filmmaker has complexity in mind in Palindromes. Even the movie’s vaunted casting gimmick is more reductive than elucidating. The same girl, Aviva Victor, is played by eight actors, most of them playing her at the same age (roughly 12 or 13). Among the performers are a (briefly seen) boy and Jennifer Jason Leigh, who was 42 at the time the film was shot. Lest anyone suspect this casting stunt is meant to elaborate on the flowering of character, Solondz has a character declare the film’s philosophy near its end: That all a person’s character is set early in life and, though we may gain or lose weight or undergo other such superficial changes, we remain essentially the same our whole lives through. The casting, then, suggests not that a person contains a multiplicity of selves, as one might have supposed, but that regardless of appearances, only a single self, and a pretty barren one at that.

The movie actually opens at the funeral of Welcome’s Dawn Wiener, quickly followed by a scene with little 5-year-old (or thereabouts) Aviva, played by a chubby African-American girl. She’s having a conversation with her mother that more or less sets the tone for what follows. Joyce Victor (a facially-smooth Ellen Barkin, who is actually quite good) answers Aviva’s question about the late Dawn’s life with careful locutions that, even if you haven’t seen Welcome, would produce a snigger of recognition at least as much as they would a fond smile. Little Aviva replies that she’s going to have lots of babies, so that she will always have someone to love.

The movie then concerns itself with Aviva’s attempts to become pregnant, an effort that follows soon upon her ability to ovulate. On a visit to family friends, she (now a pubescent brunette white girl) sleeps with a surly kid about her own age, does in fact become pregnant, and then is forced into having an abortion by her mother.

At this point, Palindromes still looks like its going to turn into something tough-minded but rewarding. When Aviva and the boy, Judah, couple, it is one of those wonderfully icky episodes that Solondz insists sex so often is. When Joyce tries to persuade her daughter (transformed into a redhead) that she must have an abortion, she relates the story of her own abortion with details that tread a line between the appalling and sentimental, self-serving and realistic. It’s one of the best displays yet of Solondz’s skill as a satirist.

The pattern holds through Aviva’s encounter with a slack-jawed truck driver willing to aid in Aviva’s quest. But things fall apart shortly thereafter when, roaming through the countryside on her own, Aviva – now played by a morbidly obese African-American girl – is taken in by the Sunshines, a married couple who are raising a passel of kids with various disabilities.

The problem isn’t that Solondz has fun at the expense of the Sunshines. Indeed, they represent a segment of society that cries foul at the slightest hint of criticism, which makes them particularly suitable targets for satire. But Solondz focuses on trivialities, as when Mama Sunshine, worried that Aviva might leave, remembers a girl “who ran away and didn’t even have any legs.” Solondz even stages a musical number with the kids, the easiest setting for pure, limp camp.

This paltriness casts a shadow in both directions. The earlier sequences lose some of their potency in the vaporous camp. To regain some emotional strength after the Sunshine episode, Solondz turns, not unexpectedly, to the cheap dramatics of violence.

After all this, the writer-director has a recurring character – Dawn’s brother – express the film’s dead-end philosophy in so many words.

Solondz has usually been a foe of the sentimental. But sentimentality – and cynicism, which is also apparent here – is an adjunct of camp. Watching Solondz submit to it is the most distressing sight in Palindromes.