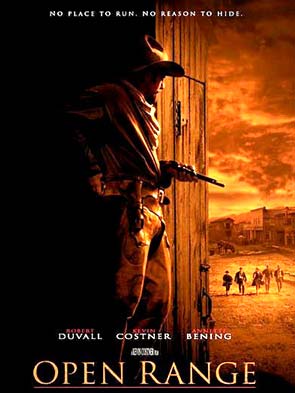

Open Range is the least ambitious movie Kevin Costner has directed and, through no coincidence, is the best. That it is the best doesn’t vault it up to the level of marvelous or even all that good. It is way too talky (with some pretty laughable dialogue about "killin’"), the characters too simplistic (unless Costner set out to make a "B" western), and, at 138 minutes, it’s too long. The movie is also shot in a style that began to infect some westerns in the 1960s, monumentalizing images to the point where they became static and meaningless.

Open Range is the least ambitious movie Kevin Costner has directed and, through no coincidence, is the best. That it is the best doesn’t vault it up to the level of marvelous or even all that good. It is way too talky (with some pretty laughable dialogue about "killin’"), the characters too simplistic (unless Costner set out to make a "B" western), and, at 138 minutes, it’s too long. The movie is also shot in a style that began to infect some westerns in the 1960s, monumentalizing images to the point where they became static and meaningless.Open Range does have a nice, long gunfight at the end, though. Before Robert Duvall’s character starts rambling on in the actor’s too-precise accent, the dialogue is gratifyingly laconic. Costner, who along with Duvall plays one of the two leads, keeps his actorly excesses in check. There’s lots of horses. That’s about it on the plus side, but with westerns pretty spare these days, that’s what some of us are willing to live with.

In genre terms, this is a revenge western. The drama springs into action when a quartet of cattlemen headed by Boss Spearman (Duvall) have their cattle rustled by a local rancher, one of the four being killed and another seriously wounded in the process. The rancher, a land baron named Baxter (Michael Gambon), is a sworn enemy of "free rangers," who roam over the plains feeding their cattle on unfenced land before bringing them to market. Baxter’s reaction to the appearance of free rangers’ is obviously extreme, but unknown to him, one of the free rangers is pretty extreme in his own reactions.

That ranger is Charley Waite (Costner), Spearman’s number one hand and his trail mate of ten years. To just about everyone’s surprise – not to say shock and fear – Charley turns out to be a former professional gunman with a ruthless sense of justice just about indistinguishable from Jacobean-style vengeance. You can imagine the rest, though perhaps not how long it takes.

Costner, working from screenwriter Craig Storper’s adaptation of Lauran Paine, is unabashedly saluting westerns of the past with his movie. But while he may be aiming to invoke John Ford or Howard Hawks, the names that come to mind most often are John Sturges, Henry Hathaway, and Andrew McLaglen. Directors of the second rank, all three of these men did good work, but they also turned out a lot of lackluster stuff, too.

As did Sturges (The Magnificent Seven, Joe Kidd), Costner has fastened onto the idea of the professional gunfighter who, once unleashed on his enemy (always an unmitigated son of a bitch – make that sumbitch), is unstoppable in his murderous efficiency.

Like Hathaway’s late westerns (The Sons of Katie Elder, True Grit), Costner’s is saddled with an elaborate, distracting version of western patois that borders on parody. This gets risible in the scenes between Charley and his love interest, Sue Barlow, played by Annette Bening. Sue keeps telling Charley that despite his past, she knows he’s a kind, gentle man. He allows that, yep, he might be. When he tells her that "a lot of men are going to be killed today and I’m going to be doing a lot of the killing," Sue just smiles and tells him something about how all that won’t touch the core of his gentleness. These combinations of down-home eloquence and homespun morality are always unfortunate, but in Open Range – as in Hathaway’s movies – they’re madly persistent.

Finally, Costner cannot resist the temptation to set up his camera in the most heroic positions he can find. This is fine for establishing shots that show his characters doing something heroic; herding their cattle through a valley in the face of a brewing storm, for example. But when a couple of riders are just fording a relatively shallow river on their way back to camp, and the camera’s shooting them from about a mile overhead, you have to wonder what the point is.

McLaglen, the son of actor Victor McLaglen and a former assistant to John Ford, used to fall into the same artistic fallacy (Cahill – U.S. Marshall). The problem with this kind of imagery is that it robs your film of two opportunities. First, if you avoid going for the picturesque shot every time out, you have opportunities to go in for closer shots that offer more information. If we could see those two riders – Charley and Boss as it happens – face on as they cross the river, we could see their individual feelings, compare their postures and attitudes, and even the nature of their relationship. But we miss out on that at that moment. Secondly, those big picturesque shots become merely picturesque. When a director places characters against the spaciousness of the western landscape he or she can render a lot more than a beautiful canvas. He can sketch a moment in a way of life, describe an emotion, use composition to underscore a change in an era. It doesn’t just have to be pretty or heroic pictures.

Still and all, Open Range is a western and they don’t make much of them. You take what you can get.