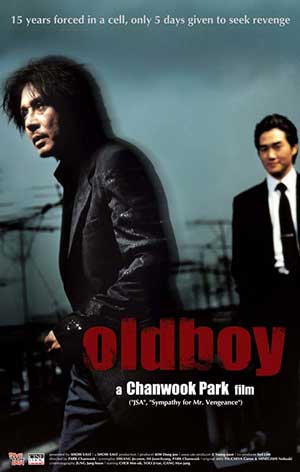

Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy’s seething concoction of sexuality, violence, and cinematic ingenuity doesn’t lead to quite exactly to the climactic explosion one expects – at least given its unceasing uproar till then. But then, South Korea’s own modern history of turmoil and dislocation hasn’t led to revolution, either. Although not overtly a political film, Oldboy is about the distortions of personality that occur under modern, ruling-class formations. It’s an angry work, and only avoids bitterness by balancing its hopes on the thinnest of imaginable remedies. With it, Park has fashioned one of the most important movies to emerge from South Korea, one of world cinema’s current hot spots. True, thanks to its harshness, it’s not a film likely to be “liked” by a lot of people, but it demands to be grappled with.

Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy’s seething concoction of sexuality, violence, and cinematic ingenuity doesn’t lead to quite exactly to the climactic explosion one expects – at least given its unceasing uproar till then. But then, South Korea’s own modern history of turmoil and dislocation hasn’t led to revolution, either. Although not overtly a political film, Oldboy is about the distortions of personality that occur under modern, ruling-class formations. It’s an angry work, and only avoids bitterness by balancing its hopes on the thinnest of imaginable remedies. With it, Park has fashioned one of the most important movies to emerge from South Korea, one of world cinema’s current hot spots. True, thanks to its harshness, it’s not a film likely to be “liked” by a lot of people, but it demands to be grappled with.

Immediately following a short, confusing scene during which a wild-haired man dangles another from the edge of a high-rise, the movie’s principle narrative opens in a Seoul police station, where businessman Oh Dae-su (Choi Min-sik, who is rivetingly ferocious), is making a drunken nuisance of himself. Dae-su had been on his way home from work with a birthday gift -- angel wings -- for his 3-year-old daughter, but whatever respectability that errand may bespeak is undone by his obnoxious behavior, which even turns off the various ruffians forced to share a bench with him. Only the timely appearance of his friend, Joo Hwan, rescues Dae-su from a night in the pokey.

Joo-hwan gets Dae-su to call home from a phone booth, but while the solicitous friend takes a turn talking to the birthday girl, Dae-su mysteriously disappears. The movie cuts to a prison cell, where, with the help of a voice-over delivered by Dae-su from some time in the future, we find out the businessman has been – will be – imprisoned for 15 years. The twist is that it’s a private set-up, a hidden penitentiary for those who can afford to have their enemies kidnapped and locked up. Dae-su’s nemesis has not only paid for the 15 year stretch; he’s refused to make himself known, an extra prod to Dae-su’s deteriorating condition. The prisoner sits at a desk in his comfortable cell, which resembles a very comfortable studio apartment sans kitchen, and writes out a lengthy list of people he’s offended or injured enough to have plotted this revenge.

Park is playing a very complex game with our sympathies here. Obviously, we’re sympathetic to Dae-su for a number of reasons. For one thing, any pent-up prisoner is bound to elicit our pity, especially if he hasn’t committed any crime (which we know Dae-su hasn’t, because he’s been released from police custody). Even in terms of the film’s structure, we’re inclined to take Dae-su’s side of things; the camera’s focus has been on him from the film’s beginning, so we’re taking the movie’s narrative journey together with him; in a way, he’s our empath.

But Dae-su’s behavior in the police station was not that of a “cute” drunk; it was thoroughly off-putting. Moreover, Park shoots Dae-su steadily from the viewpoint of the desk sergeant (whom we never see), who is the character who must take the brunt of Dae-su’s misbehavior. And, as mentioned, when Dae-su writes up his enemies list, it is prodigiously long.

Still, we’re not repulsed, thanks in part to his voice-over. Dae-su speaks that narration in a calm, detached manner that, nevertheless, suggests a wounded psyche (another example of Choi Min-sik’s skill). The voice augurs a greater trial to come and evokes our sympathy for Dae-su if, for not him-in-the-moment, then for him-in-the-future. Perhaps the him dangling the man from the high rise, because by now we know that it’s a post-prison Dae-su who is in fact the man from the opening film snippet.

Dae-su’s imprisonment begins in 1988, the last year of the rule of Chun Doo-hwan, a brutal and murderous military dictator who ruled South Korea with the help of a secret police force, intimidation, indoctrination, and all the tools of a modern authoritarian state. Dae-su has a television set in his cell, so he is able to watch political developments more or less as they occur. But they come at him in the weird, leveling flood typical of TV images. The return of political dissident (and future president) Kim Dae-jung, for example, is given no more (and no less) emphasis than the wedding and subsequence death of Princess Diana. Dae-su’s greatest television fixation is reserved for a young singer he seems to regard as his lover, but most of the time he flicks from channel to channel. Politics and sex, both a factor of imprisonment, get all mixed up in the gently pulsating beam.

Politics – particularly as its understood as the control of one group (even if it’s a group of one) by another – sex, and imprisonment are really what Oldboy is about. You could schematize those three elements by arguing that Park presents us with a South Korea that still hasn’t thrown off the imprisoning mind-set of its authoritarian past, if for no other reason that too many of the capitalists who got rich under the likes of Chun are still in charge. For doing the bidding of the owning class, the South Korean middle class is paid off with a comfortable living; but they’re locked in. Even when they’re literally released from a cell, there are social and political strictures that prevent them from doing what they want. These internalized rules distort normal desire, leading to….

That kind of analysis leads us away from Oldboy’s status as a movie, of which it is a hellacious example. Park’s mastery of form is so nonpareil that it would take ours to recapitulate his sequences in words.

Let’s just say that Dae-su is, after 15 years, released from his prison and wanders into a sushi bar where he meets Mido (Kang Hye-jeong), an 18-year-old sushi chef with whom he soon takes up. During this middle section, Dae-su is contacted over a cell phone he’s slipped – and, eventually, through email – by the mysterious man who paid for his imprisonment. Dae-su also tracks down the prison’s location and wreaks a little revenge of his own on his hired jailers.

This middle section is, at times, extremely violent, though the physical violence seems perfectly appropriate when you match it up to the psychic violence. Also, Park throughout the film, has employed distancing devices. He’ll use a medium shot instead of a close-up whenever he can, a long-shot instead of a medium shot. His camera movements aren’t virtuosic to the point of being annoying, but just stately enough to remind us we’re watching a movie. The movie’s big fight scene – during which Dae-su pummels a platoon of pole-wielding thugs with a hammer (and wins) – is filmed in a beautiful, long, Godardian parallel track. Just before the fight begins, when Dae-su holds his hammer over the head of his first victim, a dotted line suddenly appears on screen tracing the path the hammer will take to the man’s pate.

Park’s visual language can be lovely, as well. In his cell, Dae-su had been susceptible to hallucinations in which ants had crawled all over his face and arms and under his skin. Mido, who reads about it in his journals, tells him she feels bad for him; she’s read that people who dream about ants are lonely. To show the idea of loneliness and ants as Mido imagines it, Park uses a computer trick to have an oncoming subway car cross the frame from upper right to lower left; whether intentional or not, it mimics the motion of the engine in the Lumiere brothers’ 19th-century L’Arrivée d’un train en gare de la Ciotat. When he cuts to the inside of a train car, it’s empty but for Mido in one corner, all alone, and a placid-looking giant ant all alone in another. It’s an antique moment, strangely serene, odd, and wholly different from Dae-su’s experience.

The middle portion of Oldboy belongs to Dae-su and Mido, their burgeoning relationship and how it tries to take hold under what turns out to be the surveillance of Dae-su’s foe. The final third belongs to Dae-su and that foe who, by then, has openly revealed himself and prodded Dae-su to discover the source of his enmity.

We live in an era of revenge movies, just as the English under James I lived in an era of revenge dramas. For the most part, our movies play out their hunts for bloodthirsty vengeance blindly, never questioning the ends they pursue or the spurs that set them in motion.

Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy delivers a package of filmed vengeance that is steeped in rage and violence. But it’s also a rigorously introspective movie, of the times but also for the times.

NB: Just to confess a personal interest: I was paid to write the American press notes for this film.