So, there’s these three guys, an old man and his two middle-aged sons, see. The geezer had three wives, but he wants to search for the first; one of the sons has six wives and has an eye out for a seventh; and the second, well, he’s never had any and who knows what he’s looking for.

So, there’s these three guys, an old man and his two middle-aged sons, see. The geezer had three wives, but he wants to search for the first; one of the sons has six wives and has an eye out for a seventh; and the second, well, he’s never had any and who knows what he’s looking for.

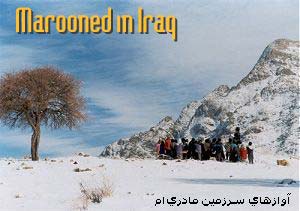

If Bahman Ghobadi’s new film, Marooned in Iraq, starts off sounding like an elaborate joke, that’s the point. Moving forward from the grindingly harsh reportage of his first feature, A Time for Drunken Horses, the Kurdish filmmaker – and for now, we do mean the Kurdish filmmaker – has decided to look at life through the all-seeing, but forgiving lens of comedy.

It’s not that the harsh Kurdish life isn’t represented. The characters must navigate the snow-clad peaks that are the salient geological feature of northeast Kurdistan. Worse, it’s 1991, and though our heroes are at least nominally safe on the Iranian side of the border, tens of thousands of Kurds from the Iraqi side are pouring over the invisible frontier between the two nations. They’re fleeing the vengeance of Saddam Hussein after rebelling at the instigation of Bush 41 and then being left out on a quickly snapping limb.

Ghobadi turns away from none of this – on the contrary, he often highlights it – but he’s more determined to show how life goes on. His main vehicle for that, is a famed singer named Barat (Faegh Mohammadi, a musician who, like nearly everyone else in the cast, is an unprofessional actor), who finds that a nagging family can tug at you even more insistently than history.

Ghobadi displays what will turn out to be a typically cheeky wit in introducing Barat, initially showing him at the steering bars of his motorcycle, then revealing that driver and bike are riding on the rear of a flatbed truck. These bang-bang introductions run like rhythmic backfires all through the movie. A few minutes later, it’s Barat’s brother’s turn. Audeh (Allah-Morad Rashtian), the guy with six wives, turns out to be a homely, braying barge, complaining at the top of his voice as soon as Barat hies into view and literally charging out of an outdoor shower to chase his brother as he put-puts his motorcycle into park.

Audeh’s chief complaint is that their father, the aged Mirza (Shahab Ebrahimi), wants to go to the Kurd refugee camps along the Iraq-Iran border and search for his first wife, Hanareh. Mirza and Hanareh, along with their friend, Seyed, had been part of an almost legendary musical group until it broke up, apparently over sexual tension. Hanareh, at least, had ended up married to Seyed. Now, Mirza is claiming that he never properly divorced Hanareh, that the family honor is thus compromised (an extraordinarily serious problem), and that he must go find her and divorce her. That Hanareh may be caring for victims of gas attacks is mentioned almost as an aside.

Even by this time, which is essentially only the picture’s set-up, Ghobadi has swerved right and left to net offbeat characters or fatten his main characters. Barat especially emerges as what a Western audience can only presume is an exemplary model of some sort of Kurdish manhood. He’s strong, but kind. He’s also riven by anxiety, too conservative for a woman he falls in love with, and too impulsive for his own good. Yet, he’s capable of self-analysis and change.

In other words, he’s a perfect candidate to hold together a picaresque tale, which Marooned in Iraq quickly becomes. As in any such tale, the travelers are robbed, meet up with people worse off than they are, are captured by local chieftains, and, in Barat’s case, is seduced by an unseen woman’s beautiful voice.

Internally, the trio provides comedy and music. The comedy comes largely through non-stop bickering, most of it provided by Audeh who, out of deference to his father, redirects his ire to his long-suffering brother. The music, which comes is relatively short doses, is magnificently strong. Audeh plays a drum called a daff and Barat a reed instrument and they both sing together as the audience claps or dances along. It can be tremendously exciting even when, as in a wedding sequence, they do it under armed threat.

As the three move westward, Hanareh continues to elude them; at the movie’s midpoint, they cross into Iraq and the devastation and human suffering begins to move towards the forefront. Even then, Ghobadi manages to wring humor from a situation. Audeh has been looking for a seventh wife because none of his other ones have been able to give birth to a son. At an orphanage, standing in the middle of dozens of parentless boys, he proposes to a pair of beautiful young women, who give him the "are-you-kidding?" treatment in what could have been one of the movie’s funniest scenes. Yet, the issue of the orphans militates against laughs in what comes to be an increasing surge of tragedy and bitterness into the film.

In the end, Ghobadi finds a way for love to offer a ration of redemption. But it’s not the All-Clear that we’re used to. Almost literally, each of the heroes manages to snatch a life away from the graveyard, a graveyard which may have been too full anyway.