The second Lord of the Rings film, The Two Towers, is opening with the quiet dignity of a Saturday night beer blast, reserving for itself all the Hollywood hoopla that used to spread itself out over several films every Yuletide.

The second Lord of the Rings film, The Two Towers, is opening with the quiet dignity of a Saturday night beer blast, reserving for itself all the Hollywood hoopla that used to spread itself out over several films every Yuletide.

Well, good for Peter Jackson. The still-young (41) New Zealander took on a difficult project that he’s made practically in his backyard and done a very good job of it. Unfortunately, if you say "very good job" instead of "breathtaking masterpiece," you will sometimes find yourself at the mercy of savage Tolkien-ites who accuse you of desecrating their beloved tale by underestimating both the original books and Jackson’s unsullied adaptations.

My wife is an emotionally reasonable, but intellectually committed fan of both the books and the movies and has an unbridled enthusiasm for Two Towers. She called it "great," a word I’ve never heard her direct with such fervor towards a movie. And playing Van Helsing to my Dracula, she warded off my criticisms with the declaration, "I suspect the movie doesn’t stand on its own but I don’t care.’’

Fine. But what about those of us who do care? We sat through the first movie and were informed that the trilogy was an allegorical quest based on the efforts of Frodo (Elijah Wood), a Hobbit, to throw a powerful, magical, but character-distorting ring into a volcano, lest it fall into the hands of evil, destructive forces. Now the second movie turns out to be a three-hour detour during which Frodo’s band, the Fellowship of the Ring, is broken up into thirds, each going off to have separate adventures.

Frodo and his aide-de-camp, the Hobbit Sam (Sean Astin), run into a peculiar, goblin-like creature called Gollum (a combination of Andy Serkis and incredible CGI work that advances the technology at least one generation and pumps enormous life into the movie). Gollum once possessed the ring, and his physical, mental, spiritual and emotional deterioration (he’s a pathetic babbler who exists solely to get the ring back), is both a danger and an example to Frodo. Gollum promises to take Frodo and Sam to the belly of the beast, so to speak, the tower at the fortress of the "dark lord" Sauron, in the land of Mordor.

Two other Hobbits, Merry (Dominic Monaghan) and Pippin (Billy Boyd), end up in a forest with a walking, talking old tree named Treebeard. Another superb effect that blossoms into a spectacle at the end of the movie, this portion of the film is the repository of is gentler feelings.

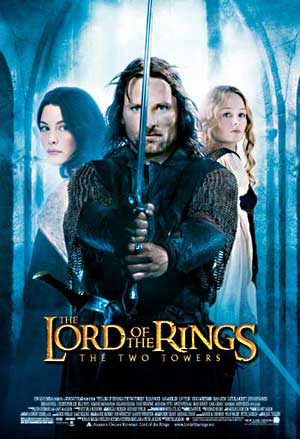

Finally, the action-filled and longest sequences feature the human Aragorn (Viggo Mortensen), the Elf archer Legolas (Orlando Bloom), and Gimli the Dwarf (John Rhys-Davies). They end up in the kingdom of Rohan, whose king, Theoden (Bernard Hill), has been bewitched by an evil advisor, Wormtongue (Brad Dourif). Wormtongue is an agent of Saruman (Christopher Lee), an evil wizard working with Sauron, from his own evil fortress, the tower at Isengard (now we got our two towers).

Allying with the king’s beautiful niece Eowyn (Miranda Otto) and her brother Eomer (Karl Urban), Aragorn and company break the spell over the king and prepare for a huge showdown against Saruman’s massed forces. The enormous siege-and-resistance battle between the Saruman’s armies and the Rohans at the latter’s castle, which is intercut with a massed trees’ charge at the end of the Merry/Pippin sequence, compose the movie’s climactic spectacle. The "wow" factor is very, very high.

That’s a lot of plot, but it’s not all that much story. You would think that anyone – even an Elf or a Hobbit, never mind a human – would emerge from such adventures not just bloodied and bruised, but affected in spirit. Aragorn in particular ought to endure some emotional twists and turns. For he’s not only fought a huge battle against overwhelming odds, but he’s fallen for Eowyn. His new love must vie with his old, for his memory keeps summoning promises made to his old flame, the Elf Arwen (Liv Tyler), from a-way back in the first movie.

But Aragorn is the same guy at the end of these adventures that he was at the beginning: Determined, short-tempered, but otherwise a bit bland. The same could be said for all the heroes except for Frodo, who undergoes quite a bit of agonizing on his via dolorosa. But Frodo is being worked upon by an external force, the ring. The pervasive stasis reaches a comic zenith (or nadir) in the good wizard Gandalf (Ian McKellan), who actually dies at the end of the first movie and comes back to life in this one, largely unchanged as a result of the experience.

Pleading the case that The Lord of the Rings is an allegory and so doesn’t require its characters to weather anything so vulgar as shifts in personality doesn’t fly. The hero of Pilgrim’s Progress endures plenty of them, so there’s nothing prohibitive inherent in the form.

Moreover, there’s internal evidence in Two Towers that Tolkien and Jackson approve of psychological movement when it suits them.

Only twice do characters judge others on what we would call their merits. Ethics and morality are usually left up to some moral code that various races and nations throughout the book live by. The first time comes when Frodo spares Gollum’s life out of pity and a "feeling" that he’s basically a good PERSON.

He’s right. Gollum is by far the most malleable, and hence, in real terms, the most human character in Two Towers (the movie). Since he constantly talks to himself, we can hear his mind at work, and since he’s neurotically insecure, he’s constantly reassessing his situation. A large twist in the plot depends on the second judgment, Gollum’s assessment of Frodo’s moral make-up. Gollum’s makes a mistake, and he turns vengeful and selfish as a result, but these are sins of weakness, not evil. Again, humanity stakes a rare claim on a character.

Jackson also reserves a certain kind of close-up for Gollum. Altogether, the director stays away from too many close-ups and when he does use them, they tend to be somewhat loose and action-oriented. That is, we go in close on a face so we can see how, say, Aragorn has just seen something that will cause him to act a certain way. His looking is part of a series of external actions: Someone moves, Aragorn sees him, he lifts his sword.

Jackson doesn’t use many tight close-ups that are meant to explore internal states. That is someone feels something, his face changes expression, his feelings change, his expressions changes again. But he does with Gollum. He can do that – and once you see that movie, you’ll see that this doesn’t bear enough repeating – because Gollum is such a miraculous creation. He has, simply, the most expressive facial features of any of the movie’s characters.

But he also has the most active emotional life, loaded with internal conflicts that in some films play themselves out best across the battleground of the face. Gollum’s visage is the scene for this spiritual warfare even more than Frodo’s. And despite all the those titanic slaughters featuring walking trees and resurrected wizards, Gollum’s struggles are far more plaintive and individually soulful than any others.

They’re also more cinematic. What? What! A single character’s face more cinematic that a wide screen’s worth of battle? Yes, if that character’s face carries an emotional truth that the battle lacks, or lacks in such measure. As my wife explains it to me, fans of the trilogy need the battle of Rohan to find its important, dramatic place on the screen because of the place it has in the second book.

Books can be discursive by nature and perhaps Tolkien even felt he needed to be discursive in this case. A new nation, a great battle scene, the separation of a group of characters, all help to spread the dramatic vista, enliven the action, and individualize a growing mob of characters.

But movies don’t need that because of the immediacy and physicality. The vista is there before you, the action is ever-present because the characters are always animated, and every characters is individualized through speech, size, gesture, gait, costume, etc.

So perhaps The Two Towers exists really just to please the fans of the book and to present movie fans with an entertaining entr’acte. Except that here in the noise and the clutter we find pathetic Gollum, a twisted, gray chatterbox, untrustworthy, full of bad judgment, and unforgettably human.