George Romero’s zombies have come a long way since we got a first ghastly look at them in 1968’s Night of the Living Dead. Literally, of course, they’ve only made it from rural western Pennsylvania to Pittsburgh – though that’s not so bad for creatures who drift about randomly and slowly, hoping to run into human meat on the hoof.

George Romero’s zombies have come a long way since we got a first ghastly look at them in 1968’s Night of the Living Dead. Literally, of course, they’ve only made it from rural western Pennsylvania to Pittsburgh – though that’s not so bad for creatures who drift about randomly and slowly, hoping to run into human meat on the hoof.

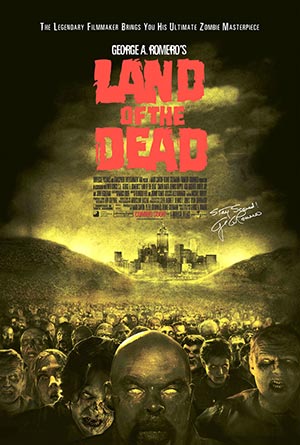

But in Land of the Dead, the fourth installment of Romero’s ongoing epic of the living and the dead, the walking corpses form the beginning of an actual social group. Under the growling, howling direction of a dead gas station attendant (Eugene Baker), a group of zombies begin to make their organized way from the suburbs to the city. Most of the countryside has been ceded by the surviving living to the dead, but many cities – including Pittsburgh (Toronto doing a lot of subbing for same) – have barricaded themselves with electrified fences and army units.

These islands on the land are not havens of democracy. While most of Pittsburgh’s streets are filled with people in various states of deprivation, a towering shopping mall and condo building named Fiddler’s Green houses the privileged hundreds. Rather than a president, an entrepreneur, Kaufman (Dennis Hopper in, surprise, an effectively restrained performance) rules the roost, providing amenities, security, and a closely-guarded waiting list in return for fat fees.

To keep his people well-fed, Kaufman sends out raiding parties of specialized fighters, daredevils who drive into small towns at night and, risking infection or worse from resident living dead, carry off food supplies. The boss of the force is Riley (Simon Baker), a thoughtful type who, when the action starts, is leading his last raid. Tired of butchering the dead for the comfort of the pampered, he’s heading out for northern climes where there are neither zombies nor people. In contrast to Riley is Cholo (John Leguizamo), an enthusiastic zombie-killer whose dream is to make enough money to move into Fiddler’s Green and become a member of the ruling elite.

Probably the most salient feature of Land of the Dead is how it demonstrates Romero’s ability to stay ahead of the moviemaking pack. Now 66 years old, the director has construed a maelstrom of action that young filmmakers can only dream about. It’s fascinating to recall how Romero’s technique has developed over the years, with a style originally tailored to a bare-bones budget now supplemented, but not replaced by, a less budgetary-conscious approach.

When Romero made Night of the Living Dead 37 years ago, he didn’t have the money for either the expressive lighting effects associated with horror films or for a lot of different set-ups. He chose, instead, to film documentary-style, with long, black-and-white shots. Less a mere reaction than an enriching technique of its own, the approach provided some of the most profoundly creepy images in the history of horror filmmaking. Even now, for example, the initial shot of a corpse staggering in the deep background towards the brother and sister visiting a cemetery retains its iconic power.

Aside from the power of effects, the use of shots which emphasized shared space and time gave the film its substantial psychological edge. The time we spend with the dead – or, more precisely, the time we try not to spend with the dead – is the visceral revulsion at the core of all four films. The eerie suspense that these long, depth-of-focus shots would then climax with space-shattering shock cuts or intrusions into the frame, the two techniques combined in the powerful, memory-haunting images of the zombie arms crashing through boarded-up windows.

In Land of the Dead (which had a $15 million budget, modest by any measure except for Romero’s), the director deploys the shock-cut style to dizzying, occasionally giddy extremes. Deliberately playing off the audience’s fear and self-consciously trying to top himself, Romero doesn’t let a window, door or closet pass by that isn’t harboring a zombie or six or 12. Elaborating on this deceptively simple editing style, Romero will have a character occupy a large, dark, apparently empty space (a shack, a warehouse) for relatively long periods of times before allowing a member of the walking dead to, not suddenly, but still frighteningly, shamble out of the dark.

The director plays an even richer variation on the temporally extended shots. In the earlier films those were used solely to embrace the living and dead within the same time and space, i.e. the same world – and Romero continues that use in Land. But now those shots are increasingly used just to show all the dead together. The intent is to show us the gruesome flesh-eaters’ dawning intelligence, as they begin to react to orders (from the pump jockey) and cooperate as a group. But they also demonstrate that one of the human impulses that survives death – along with appetite – is the tendency for group’s to break down into classes. Just as the living populate different areas of Pittsburgh according to their social and financial status, so too, much more crudely, are there privileged leaders and anonymous followers among the dead.

The dead of Land, then, continue to do what the animated corpses of Dawn of the Dead did, which was to hold up a distorted mirror to the living. What’s new in Land is that the mirror doesn’t need to distort all that much. The organized dead, for example, don’t know what they’re after until they reach the outskirts of Pittsburgh and they gaze up at the luminescent Fiddler’s Green. From the moment they see it, they strive to reach it, obviously to commit cannibalistic mayhem (and how!), but also to reach some sort of dimly apprehended sanctuary.

This is the exact same ambition held by Cholo, the profane, careless, and violent raider. Characters like Cholo usually go one of two ways: Appealingly roguish or merely criminal. Although Leguizamo gives a somewhat charismatic performance, Romero definitely shades Cholo to the greedhead side. Still, the character’s dream of the high life is oddly ennobling, as if his thought of life without struggle was somehow something more than material.

So it isn’t just the fact that Cholo is a low character that makes him like the zombies. Not that Romero doesn’t identify mankind’s baser appetites with the living dead’s: There’s a scene in an after-hours pleasure dome where, among other sideshows, a woman (Asia Argento, who goes on to play a major role) is placed in a cage with two unchained zombies to fight for her life. Who are the monsters, indeed.

But Romero does find something to grab onto, some shred of humanity, in both Cholo and the zombies (Kaufman, too, to get down to it). This is what makes Land of the Dead, and the other three living dead films, so much more than mere shockers (though they are sublime shockers). Romero finds humanity both distasteful and irreducibly salvageable. We may be little more than zombies in our daily lives, but we still look at the stars.