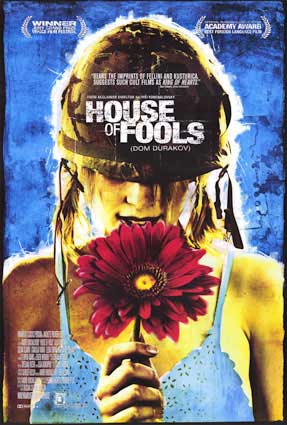

Having watched House of Fools, one can only pray that the this won’t be the last film of 65-year-old Andrei Konchalovsky. The movie is on such a wretchedly hackneyed conception – the madhouse in wartime – that it would be a shame if it were to be the capstone on a sometimes distinguished career.

Having watched House of Fools, one can only pray that the this won’t be the last film of 65-year-old Andrei Konchalovsky. The movie is on such a wretchedly hackneyed conception – the madhouse in wartime – that it would be a shame if it were to be the capstone on a sometimes distinguished career.

Konchalovsky director has had a unique, one might almost say peculiar record, beginning in his native Russia where established his reputation with the likes of Uncle Vanya, a delicate adaptation that was a prize winner at San Sebastian in 1971.

Konchalovsky had run into trouble with the Communist Party just a few years earlier, in 1967, when they banned his second feature, Asya’s Happiness (a ban which lasted till the end of the party’s dominance, in 1988). In an interview I conducted with Konchalovsky in 1987, explained the dilemma he and his peers were likely to fall into: "The Communist Party has no interest in what you have to say as an artist, but a great deal of interest in what you have to say as a citizen." Yet, he didn’t fall entirely into a period of poltical quiescence, for after his success with what seemed like apolitical dramas, he turned out the politically-inflected quasi-epic – and internationally successful -- Siberiade in 1979.

Konchalovsky accepted an invitation to make films in the United States, a move that met with. Artistically, there’s no question that Maria’s Lovers (1985), Runaway Train (1985), and Shy People (1987) were all superb movies, among the director’s best. Unfortunately, all three were under or mis-appreciated to some extent or another, particularly Shy People. Konchalovsky’s last two American films were a little strange, the bizarre but intriguing Homer and Eddie and the purely commercial Tango and Cash (1989) (Konchalovsky meets Stallone).

Whether it was because he returned to an economically and perhaps emotionally depressed Russia, or that he just can’t shake off the slump that began during his last year in the U.S., Konchalovsky has just turned up with his biggest clunker. You would think a filmmaker whose greatest strength has always been his sense of the concrete (even when dealing with such an obvious symbol as the locomotive in Runaway Train), would know enough not to descend to the depths of, shudder, moral allegory.

For once it might be nice to see a movie where soldiers invade an asylum and discover that they are saner than the inmates, by our made Andrei hasn’t made it. Set during one of the flare-ups in the ongoing wars between Russian and Chechnya, the movie’s mental hospital is just over the Chechen border in the Russian Federation Republic of Ingushetia.

To this Westerner, the exact ethnic make-up of much of the cast seemed fuzzy. Nearly all the dialogue is in Russian and subtitled, though when Chechen soldiers show up and speak Chechen, there are no subtitles; on the other hand, they speak Russian most of the time, even to each other. One of the main characters is described in the notes as Chechen, though she speaks only Russian and doesn’t seem to understand Chechen. On the other hand, the notes also describe Ingushetia as a village, so what the hey. American can hardly complain. In Hollywood films, everyone speaks English, only with an accent if they’re from a "foreign country," though we tend to know which is the country in question.

The concept is so basic and crude that it is largely resistant to individual variation, though for the record, here is Konchalovsky’s. Janna (Julia Vysotsky) is a young woman with what might be described as a sever nervous condition and a delusion that she’s the fiancée of pop singer Bryan Adams (who appears throughout the film as a fantasy figure). She’s also an accordion player whose performance of single polka is frequently enough to quell outbreaks of collective agitation among her fellow inmates.

Inevitably, the place is occupied by a military force, Chechens as it happens, though in reality it might as well be Serbians, Somalians, or Sri Lankans. Janna transfers her affections to a soldier who is initially opportunistic, then non-plussed, and finally abashed. The soldiers sing sad songs of their homeland. Russians show up, and wouldn’t you know it, the contending commanders are old comrades. The Chechens flee, the Russian occupy the madhouse and - well, you get the picture. And of course, the peaceable inmates appear more sane than the warriors.

Depending on your point of view, either the redemption or the shame of the movie is that Konchalovsky’s pure directorial skills are as sharp as ever. House of Fools has a sharp dynamism and sensible structure that sustains at least the illusion that a real drama is occurring. And Konchalovsky even manages to make the soldier Janna falls for almost rise to the level of an actual character.

But this is no way for the director of Siberiade and Maria’s Lovers to end up. Let’s have at least one more Konchalovsky effort, please.