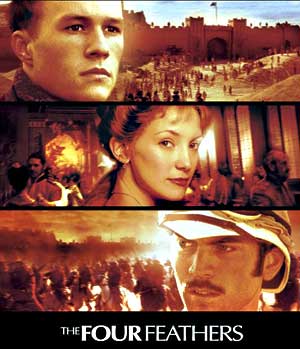

What in heaven’s name is boy actor Heath Ledger doing parading around monumental English estates in British scarlet or stumbling down cascading sand dunes in North African mufti? If you listen to the hap-hap-happy drumbeat of the Hollywood publicity machine and its thrumming echo in the popular press, you would think that the professionally stalwart youth was starring in a remake of A.E.W. Mason’s imperialistic potboiler, Four Feathers.

What in heaven’s name is boy actor Heath Ledger doing parading around monumental English estates in British scarlet or stumbling down cascading sand dunes in North African mufti? If you listen to the hap-hap-happy drumbeat of the Hollywood publicity machine and its thrumming echo in the popular press, you would think that the professionally stalwart youth was starring in a remake of A.E.W. Mason’s imperialistic potboiler, Four Feathers.

After playing various sons (Mel Gibson’s in The Patriot, Billy Bob Thornton’s in Monster’s Ball) and lovers (10 Things I Hate About You, A Knight’s Tale), Ledger gets to play a legitimate lead this time, a young English aristocrat of 1885 who refuses to ship out to the Sudan with his regiment. Tarred as a coward by his friends and girlfriend Ethne (Kate Hudson) – each gives him a white feather to signify this view – Ledger’s character, Harry Favesham, travels to the Sudan incognito, where he performs daring feats that save his friends’ lives, not to mention the empire’s stake in North Africa, and proves himself a hero.

Mason’s book – which hardly a man who’s now alive has ever read – was adapted into an equally enthusiastic imperialistic yarn by producer and impresario Alexander Korda (a former Communist cultural minister in post WWI Hungary, if you can believe it) in 1939. His Four Feathers, which was directed by his brother Zoltan and designed by another brother Vincent, is fun if you can stomach the racism (it actually has a title referring to the black residents of the Sudan as "fuzzie-wuzzies"). More importantly, it has the virtue of expressing a world view through its imagery, a world view that is imperialist and, yes, repulsively racist, but which is at least coherent.

Shot in Egypt and the Sudan, the Korda picture was quite an undertaking for the time, but it was an adventure, not an epic. Of course, we don’t have mere adventures nowadays, and the sight of all the sand in the new Four Feathers has set off the epic alarm bells. This adaptation, which, for the record, was directed by Shekhar Kapur, does occasionally go for the giant vista, the big ballroom dance, the climactic cavalry charge, but it is no epic and all of these ornaments turn out to be the cinematic equivalents of velvet tiger painting.

At first glance, coherence – not to mention craftsmanship and acting (this is perhaps the worst acted movie of the year) – would appear to be a major problem with this new Four Feathers. Harry moves from grand ballroom to barracks to teeming marketplaces to desert outposts and stifling mahdist prisons, but never with any sense of internal drive. We’re not riding waves of adventure round the British empire, just the cast and crew bus to different locations.

The movie’s climax – and you only realize it is the climax after it is over because suddenly the movie’s action ends – is a fight in the desert between Harry and a former warder. Harry has escaped a desert prison camp with the help of a mysterious, but highly lethal friend, an African named Abou Fatma (Djimon Hounsou, the former model who starred in Amistad). The beefy, enormously strong, and very, very angry head guard (his whole family was wiped out by the British) has caught up with the emaciated, thirsty, and guilt-ridden Harry and they have a big fight that looks for all the world like a professional wrestling match. Am I giving away the ending by telling you that Harry wins? And he does so not only at the last second, but because it is the last second.

This whole sequence has nothing to do with anything else in the movie. It’s just a variation on the gunfight-in-the-saloon scene; it establishes Harry’s bona fides as a tough guy. Strike that; not Harry’s, but Heath’s. And here we get to the heart of the matter, the source of the movie’s coherence. There should be no need for director Kapur, who shot the entire movie as if through a telescope, to argue with screenwriters Michael Schiffer and Hossein Amini (and God knows how many others) over the true authorship of this Four Feathers.

No, the decisive creative hands – manicured, French-cuffed – most likely belong to Ledger’s managers and agents and to the executives at Paramount who think they may have a hot little blond property on their hands. It is time, this bunch must agree, to escort young Ledger from the shoals of adolescence to the shores of adulthood and the delights of big money. Keep that in mind, and suddenly, Four Feathers doesn’t look quite so stupid.

For example, wherever they go, whatever they do, Heath/Harry and his buddies wear their scarlet dress uniforms. Heath/Harry, of course, bails on his regiment before they get to the Sudan, but his friends, including one played by another potential leading man, Wes Bentley, wear scarlet all through a desert campaign. Never once does anyone change into his tan campaign uniform because then, of course, the boys wouldn’t look their best for the camera and thus for the young ladies in the audience, for the movie clips on the interview shows and the review shows, etc., etc.

Now that’s a minor failing. For years, actresses have been stepping out of shipwrecks in unruffled evening wear. Kate Hudson, for example, never wrinkles a single formal gown no matter where she steps. But there is another discontinuity in the movie that shows how the managerial focus on Ledger’s image has shaped the film. Of the actual four feathers Harry receives, three are from his friends and one is from Ethne. The Korda version has a fairly long scene in which the complexities of love and the demands of a warrior society are resolved in the disgrace of the white feather.

But this modern Four Feathers simply elides the moment altogether. There is a moment when Heath/Harry speaks of the moment when Ethne gave him the feather, accompanied by a flashback of her climbing the stairs to his flat, but we never see her actually deliver the feather.

Why? Well, there could be a practical answer. As they show again and again during the movie, Ledger and Hudson are such terrible actors they might just be incapable of impersonating two upper-class Victorians enduring a wrenching moment (at least without provoking laughter). But, also, it is bad for Ledger’s image for him to be seen getting dressed down by a woman. Better for him to just disappear and go off on a sulk, perform great feats that prove everybody wrong, and then come back and do a little moral swaggering.

That’s the Mel Gibson approach. Gibson has been making hits based on that structural formula for seven or eight years. One hundred-fifty years ago, Americans considered that to be a laughable attitude. Mark Twain lampooned it with the Tom Sawyer funeral gag: The fantasy in which you pretend you’re dead and show up at your own funeral just to make everyone feel bad about not appreciating you when you were alive.

Today, moral narcissism runs rampant. It is the Hollywood leading man way, hatched by managers, agents and executives who, one assumes, take this attitude for maturity themselves. Losing the imperialism and racism reflected in the original Four Feathers was certainly good. Too bad this childish nonsense takes its place.