Even those of us who admire many of Lars von Trier’s films, are undaunted by his vaunted anti-Americanism (indeed, find it more advertised than present), and enjoy his Dogme dogmatism for the artistic lark that it is, can occasionally be exasperated by his woeful self-indulgence and a moral obtuseness of Brobdingnagian proportions.

Even those of us who admire many of Lars von Trier’s films, are undaunted by his vaunted anti-Americanism (indeed, find it more advertised than present), and enjoy his Dogme dogmatism for the artistic lark that it is, can occasionally be exasperated by his woeful self-indulgence and a moral obtuseness of Brobdingnagian proportions.

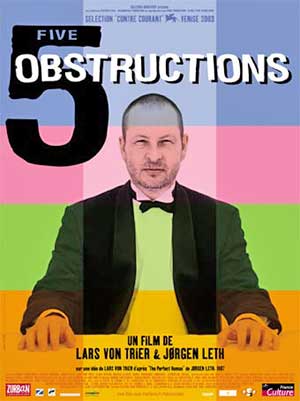

The Five Obstructions is a case study of Von Trier’s serious shortcomings, a self-constructed autopsy made in collaboration with fellow Dane Jørgen Leth. According to the notes provided with the film, Leth is a “revered cultural figure” in Denmark, a producer, novelist, poet and television commentator. OK. What he certainly is is the director of a 17-minute film shot in 1967 called The Perfect Human.

The Perfect Human’s style seems to be influenced by the Jean-Luc Godard of the Masculin/Feminin era and animated by a mild rebelliousness against the norms of Danish social democracy. Perhaps. In any event, it shows a man and woman in semi-formal dress performing everyday functions – dancing, eating, sleeping – while Leth provides faux anthropological commentary on the soundtrack. It’s a film designed to fit the phrase “small potatoes.”

In 2000, Von Trier challenged Leth to remake the film under a series of limitations – the obstructions – invented by Von Trier. He wouldn’t remake the film in its entirety five times, but take a portion of the movie – the eating, the dancing, the love-making – and reinvent it.

The two begin with the first, dancing segment of The Perfect Human, which sends Leth to Cuba. We don’t just get Leth’s finished product at first; but also get to watch him setting up his movie behind the scenes, a peek of production that produces remarkably little in the way of insight. Leth does figure out that one of the obstructions that Von Trier sets for the dancing sequence, that no shot last more than 12 seconds, is actually meaningless. The fact that you have to cut every 12 seconds in no way effects continuity or even rhythm if the filmmaker doesn’t want it to.

The film Leth ends up with is a mildly entertaining divertissement though there is a hint of what’s to come. The “revered” Danish artist includes a shot of a Cuban woman naked from the waist up. There is no nudity, partial or otherwise, in his original film, whether because of Danish mores at the time of because his actress refused to undress. Of course, in Cuba today, Leth is able to peel dollar after dollar (or whatever currency he uses), off his bankroll to cajole a poor woman from a poor country to peel off her shirt in order to give his film a “sensual” cast.

Back in Denmark, Leth and Von Trier have a good laugh over how Leth has easily surmounted the first set of obstructions. So Von Trier comes up with what he himself says is a diabolical plan. The recreate the eating scene, Leth must go to a sire of the most extreme human misery and film himself eating a sumptuous meal. Ah, this is truly diabolical, Leth agrees. The two Danish artists also agree that they will not indulge themselves with phony liberal guilt. That has nothing to do with real morality, after all.

For his site of misery, Leth picks Falkland Road in Bombay, which he has visited before. Falkland Road is a red light district but nothing like, say, the relatively clean, respectable prostitution district of Amsterdam. Falkland Road is rife with AIDS. Most of the prostitutes are children who have been forced into prostitution, who have their virginity auctioned off, who are worked to death. The depravity and perversion are unspeakable, a disgrace to humanity.

This is where, dressed in a tuxedo, Leth films himself preparing and eating a fancy meal to the music of Verdi (who would have been shocked). The ethical violation is appalling. Later in the film, Leth will recount how he tossed and turned in his hotel room for two whole sleepless nights afterwards. Poor baby. No wonder he is revered in Denmark, having such a rarified sense of morality.

Von Trier himself is unhappy with the film. He had told Leth to shoot with a plain white backdrop so that we would see nothing of the poor and oppressed. But Leth had used a semi-translucent screen as background, which allowed a few members of the “suffering masses” to press parts of their body into sight on thus into consciousness. Go back and shoot again. What an exquisite sense of artistry! But, Leth says, he cannot. He is too shaken by the experience to repeat it. What an exquisite conscience! We are indeed blessed that a country as small as Denmark has produced such a pair of towering, er, somethings.

A viewer would notice that of all the obstructions he lists, Von Trier never tells Leth to go out and actually make a movie. And, indeed, no one connected with this project ever does. The Five Obstructions is more an advertisement for the whiter-than-white sensibilities of the two principles than a film. As another critic once said of another movie, it belongs to the history of publicity, not the history of cinema.