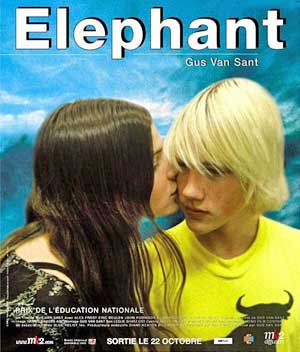

With Elephant, Gus Van Sant returns to the unabashedly personal expression of his first and third films, Mala Noche (1985) and My Own Private Idaho (1991), fashioning a morbidly romantic erotic reverie around his fascination with teenage boys.

With Elephant, Gus Van Sant returns to the unabashedly personal expression of his first and third films, Mala Noche (1985) and My Own Private Idaho (1991), fashioning a morbidly romantic erotic reverie around his fascination with teenage boys.

Van Sant’s pre-opening statements and the movie’s apparent premise notwithstanding, the film is not about the Columbine High School shooting deaths, at least not beyond a nominal point and certainly not in any empathetic, or even sympathetic, way. True, Van Sant shot Elephant in a Portland, Oregon suburban area high school that features the same general style of blandly modern school architecture that fits the Columbine type. He imposes subtitled dates on the action that correspond with the actual dates of the killings. He gives names to the characters that match up with real people, or at least with the two adolescent killers. He copies the actual course of two school days, in general terms, and the exact routes and individual murders committed by the two boys, in specific terms.

But the chill that hangs over Elephant belies Van Sant’s public assertion that he wanted to recreate the actions of the day without any glib sociological or psychological explanations for an inexplicable horror. On the contrary, the filmmaker has converted bloody incident completely to his own private use as an evocation of erotic attraction and death, converting the Romantic Decadent femme fatale into a belle Andy Hardy sans merci.

This is apparent immediately from the action’s flat tones. The same gestures and interactions are often repeated from several viewpoints that though they, no doubt deliberately, fail to expand our understanding of them, do lend them the air of ritual. Van Sant’s use of digital video recording emphasizes the technology’s persistent electronic hum, a visual equivalent of white noise that drives a wedge between the viewer and whatever is happening on the screen, prohibiting any sense of identification with the unearthly looking figures on it (anyone who actually encounters teenaged boys on a regular basis will realize how unreal Van Sant’s figures are).

For 80 minutes, Van Sant mostly dotes on four different boys: John (John Robinson), the son of an alcoholic father; Eli (Elias McConnell), a photographer; Nate (Nathan Tyson), a football player; and Alex (Alex Frost), one of the two killers. These may sound like thumbnail descriptions, but they are only as far as the movie is willing to go in describing them. Van Sant’s presentation of them is almost entirely sculptural, with the shape of an ear garnering far more of his attention than any other aspect of the boys. In that vein, the movie’s central feature is a long, hand-held shot that follows Nathan from the football field into a school building.

Van Sant’s interest in Elephant’s women is contrastingly clarifying. The only one who gets much attention on her own, Michelle (Kristen Hicks), is defined almost entirely by the fact that she’s not physically attractive. A student named Carrie (Carrie Finklea) is there to be Nathan’s girlfriend. And a trio of girls – Brittany (Brittany Mountain), Jordan (Jordan Taylor), and Nicole (Nicole George) – who are never individualized but always shown together, seem to have been presented only to depict what Van Sant must consider the shallow hatefulness of adolescent women.

To get at what’s at the root of Elephant, it’s useful to turn to the Italian critic Mario Praz, and his 1933 study, The Romantic Agony. In it, Praz traced the theme of sadism, the longing for death, and self-mortification through various Romantic figures, especially French writers and poets. But what he wrote about the French symbolist painter Gustave Moreau has an eerie application to Van Sant.

Praz wrote of “…such painting, at the same time sexless and lascivious,” a description that could apply to Elephant – or indeed to Van Sant’s previous effort, Gerry. And, as with Van Sant’s boys, “…[Moreau’s] figures have exactly the suggestion of the abstract and epicene which is characteristic of the childish imagination.”

Van Sant is drawn to the figures he has put on the screen, but he can’t quite imagine them as real. He’s like Moreau, a second-rate artist who was merely confounded by this imagery. Praz felt the poet Moreau’s superior contemporary, the poet Mallarmé was able to define this hypnotic as “the figure of the narcissist-virgin…”

That would explain why of all the characters in the movie, Van Sant ultimately settles on the killer Alex as his ultimate object of fascination. He plays the role in Elephant that Helen of Troy, Salome, and the Sphinx played in Moreau’s childishly lewd paintings, “…Fatality…Evil and Death incarnate in female beauty.”

Elephant’s final image is Alex as the embodiment of death and sexuality, the only character left alive in the film who has dealt with – or out – both of these events. But it doesn’t mean very much. Or not any more than it meant in Moreau’s silly paintings. There are, to be sure, profound and mysterious bonds between sexuality and mortality, but those bonds become attenuated as they become attached to those two stout fellow’s cousins: Lust and desire, on the one hand, and murder and suicide on the other. The first two are fundamental conditions of life. The others, at least in Elephant, are mere gestures.