Don't make an occupation out of your preoccupations. That's a lesson to be drawn from David Cronenberg's Eastern Promises, the disappointing, if not wholly unexpected, successor to the masterful A History of Violence. It was foreseeable because over his career, Cronenberg has often let his fascination with the power of spontaneous (or at least sudden) mutation in human beings overwhelm character, story and structure. This isn't a new phenomenon; it stretches all the way back to 1979's The Brood which despite its horror elements and occasions of suspense was almost a term paper.

Don't make an occupation out of your preoccupations. That's a lesson to be drawn from David Cronenberg's Eastern Promises, the disappointing, if not wholly unexpected, successor to the masterful A History of Violence. It was foreseeable because over his career, Cronenberg has often let his fascination with the power of spontaneous (or at least sudden) mutation in human beings overwhelm character, story and structure. This isn't a new phenomenon; it stretches all the way back to 1979's The Brood which despite its horror elements and occasions of suspense was almost a term paper.Even the bravura, brutal sequences in Eastern Promises have their visceral strengths undermined by a schematic conception that insists on - rather than demonstrates - the human capacity for radical, simultaneously physical and psychological change. The movie is so disjointed that the drama of ramification that so illuminated A History of Violence (and Shivers, Scanners, The Fly, inter alia) dies aborning.

When a Russian-speaking, pregnant young woman collapses in a London store, she's rushed to a hospital where midwife Anna (Naomi Watts) helps to save the life of the baby even as the young woman expires. Anna, who puts the sickly baby under her special care, discovers the young woman's diary which, of course, is written in Russian, a language Anna doesn't understand despite having Russian relatives. When her uncle, after reading the diary, refuses to tell her what it says and discourages her from finding out, Anna drops into a Russian restaurant where she asks the owner-manager, Semyon (Armin Mueller-Stahl) to translate a photocopy she brings along. Though outwardly charming, Semyon evinces an intense interest as to the whereabouts of the diary itself; Anna's knowing uncle tells his skeptical niece that Semyon has to be a criminal mixed up with drugs, prostitution, and sexual slavery.

Obviously, Anna has walked into the jaws of a massive coincidence and a world where no one is who they appear. Actually, that's not exactly true. She stumbles into a world where no one is SUPPOSED to be what they appear but who, to the audience at least, is exactly who they appear to be under their flimsy masquerades.

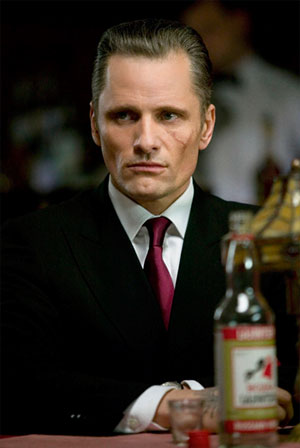

That includes Nikolai (Viggo Mortensen), the driver, bodyguard, and paid companion to Semyon's self-indulgent, alcoholic son, Kirill (Vincent Cassel). Cronenberg spends almost no time letting Nikolai keep up his pretense to the audience, though he manages to keep on fooling his supposed partners in crime.

You might assume that the prime candidate for one of Cronenberg's mutation processes would be Anna. She is, after all, a sweet person, but one susceptible to metamorphosis: After meeting Semyon, she's ready to investigate her Russian heritage but, even more importantly, her increasingly fierce attachment to the baby, sews a potential for protective rage within her. And rage, along with sexual desire, is the seed of violent, radical change in Cronenberg's movies.

But it's Nikolai who becomes the subject of perverse evolution. Eastern Promises's screenplay is credited to Steve Knight and you have to wonder how it looked before Cronenberg saw it. The plot has the outlines of a relative common crime thriller subgenre, about undercover cops who become the gangsters they're imitating.

Cronenberg revs this material up with typical élan. The movie's centerpiece is an assault on Nikolai by two beefy, fully-dressed Chechen mobsters while he's naked in a public bath. And that's naked, not nude. Cronenberg doesn't photograph Nikolai's body as an alluring deployment of flesh. Rather, Nikolai's undressed body is exposed, vulnerable, and uncontrolled. As it's beaten, Nikolai's body becomes covered with open, bleeding wounds.

Aside from being an exceptionally well-made and original depiction of violence, this scene is supposed to mark the moment that Nikolai begins his physical and psychological makeover.

But Cronenberg has Anna hanging around the periphery, trying to figure out what to do now that her behavior has been subordinated to Nikolai's. So a half-sketched relationship sputters briefly to life between the two, though it never amounts to much more than a couple of life-saving kindnesses by Nikolai and some affection from Anna that softens the Russian up a bit.

As it turns out, the beating in the baths is not just the movie's making, it's its undoing. As great an action sequence as it is, it's also a ritual evocation of a Cronenbergian transformation. But there's no plausibility attached to the ensuing behavior, a glaring shortcoming that contrasts so sharply with the enormously convincing A History of Violence.

Cronenberg has taken a modest genre fable and, instead of pumping it up, has worn it down with the weight of his professional thematic scheme.