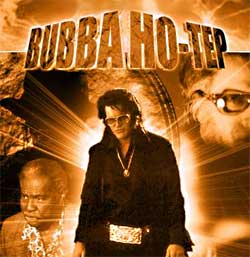

Don Coscarelli’s Bubba Ho-Tep is nominally a horror comedy about an aged Elvis Presley, alive in an East Texas nursing home, who, with the help of an equally elderly old man who claims to be JFK (despite his black skin), tangles with a soul-sucking mummy who stalks the night wearing a cowboy hat and boots.

Don Coscarelli’s Bubba Ho-Tep is nominally a horror comedy about an aged Elvis Presley, alive in an East Texas nursing home, who, with the help of an equally elderly old man who claims to be JFK (despite his black skin), tangles with a soul-sucking mummy who stalks the night wearing a cowboy hat and boots.

But silly fun though it may be – and when it comes to laughs, it’s a blast – this strange movie operates on a myriad of mind-blowing levels. Far from a simple send-up of pop culture, it carefully avoids mere camp humor and ordinary parodies of Elvisania and horror conventions. Instead, it uses its gently bizarre sense of humor to plumb questions of identity, both as experienced personally by characters in the movie and then by members of the audience as participants in an on-going drama of popular culture. At the same time, and with equal sensitivity, it insists on treating the process of aging in a remarkably serious, if frequently hilarious, way. It can merge the laughs and poignancy because Coscarelli, (who besides directing, wrote the screenplay based on an award-winning short story by Joe R. Lansdale) knows that dismay over seeing life reduced to basic bodily functions goes hand-in-hand with sorrow over life’s missed chances.

The movie’s unique tone is set immediately by an opening tracking shot into the room where an overweight Elvis, a thinning pompadour still intact, lies in a semi-light that marks his institutional days. Right away, we hear Elvis on voice-over, a device that continues throughout the film. Normally a risky maneuver, it works here thanks to the screenplay and to Bruce Campbell who plays Elvis, not just with an effective impersonation, but as an authentic character. That voice is slowed and haunted, overtaken by sighs, its sentences hinged on regrets.

But funny. For Elvis’s musing on the vicissitudes of old age is focused on a penile growth that, somehow or another, is going to have to be flattened or cut in the near future. But serious. For those musings soon grow from the physical to the emotional, as the infirmity of his love-making equipment leads to recollections of the infirmities of his love, and his grief over the way he squandered the affections of his wife and daughter. But funny because, for soon the nurse shows up and… Well, you get the idea.

The horror plot spends most of its time on the back burner as Coscarelli opens with a long and playful investigation of identity. While we first assume that Elvis is Elvis, the nursing home staff insists that he’s Sebastian Haff, an Elvis impersonator who fell into a 20-year-coma after falling off a stage. Elvis has an explanation; fed up with his life of drugs and dissipation, he had sought out Haff and exchanged lives with him. Thanks to his voice-over and flashback scenes, we tend to believe him, despite whole volumes of modern cinema that instruct us to distrust narrators (see Godard’s Masculin/Feminin). But Coscarelli cleverly uses our need for the hero of his movie to be Elvis as bait. Whether we’re fans or just want to see a hero possess an identity he believes in, we seize upon the flashbacks as "proof," even though they’re mere narrative devices within a fiction.

This is only the beginning of the identity game. Elvis himself is skeptical of claims made by other residents. He declares the African-American JFK (Ossie Davis), to be "certifiable." While that case settles into a comfortable ambiguity, there’s a third peripheral character, an old man who now believes he’s a Lone Ranger-type character who everyone knew when he was just a nice old guy. Here we have three iconic identities in different stages of development. The movie, to be sure, nudging us towards judgments over their relative veracities, to the point where we can’t really say they’re all open-ended. But compared to the sealed, bonded narratives of the vast majority of most contemporary films, it’s a riotous masquerade.

Even then, Coscarelli – whose cinematic high-water mark had previously been the 1979 horror film Phantasm (and not the mediocre sequels) – has another layer to add. When Elvis is watching his movies on television, he comments on how bad they became as he stayed in Hollywood and how he should have fired his manager, Col. Parker. Of course, if he had stayed in Hollywood till his old age, he would have appeared in just the kind of cheesy horror film that would feature a cowboy mummy sucking souls at an old folks home in East Texas.

My, my.

Naturally, at some point Elvis and JFK have to go out there and drill that mummy, and they do. Nothing ever gets scary, of course. The final confrontation begins with Elvis marching behind his walker and JFK buzzing in his electric wheelchair, all duded up in their most well-known duds. Still, Coscarelli has spent enough time on the low-budget fright front that he knows what to do, and he does it. Jaws do gape, bandages do burn.

While Bubba Ho-Tep’s low budget look helps it to a certain extent, Coscarelli doesn’t fetishize it. His set-ups are intelligent and always angled to the emotional heart of the matter. What he’s come up with his one of the most improbable marriages of silliness and pop-cult introspection ever attempted and certainly ever accomplished.

What a blast.