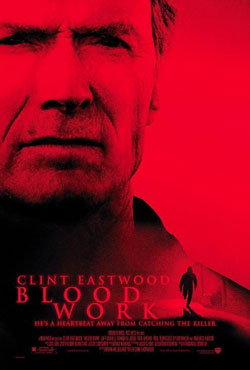

With Blood Work, actor-director Clint Eastwood continues an extraordinarily reflective part of his career, extraordinary not just for himself, but for any American filmmaker of the last 25 years. A rich and critical variation on two Harry Callahan policiers, the Don Siegel-directed Dirty Harry (1971) and Eastwood’s own Sudden Impact (1983), Blood Work could just as easily be bracketed with True Crime (1999), thanks to its rueful, laconic reflections on aging and mortality.

With Blood Work, actor-director Clint Eastwood continues an extraordinarily reflective part of his career, extraordinary not just for himself, but for any American filmmaker of the last 25 years. A rich and critical variation on two Harry Callahan policiers, the Don Siegel-directed Dirty Harry (1971) and Eastwood’s own Sudden Impact (1983), Blood Work could just as easily be bracketed with True Crime (1999), thanks to its rueful, laconic reflections on aging and mortality.

Eastwood completed Blood Work when he was 71 (and, at 72, is currently finishing up work on his next film, Mystic River). Only the most strong-willed American filmmakers make it that far: John Ford was 71 when he made 7 Women (1965); Howard Hawks directed Rio Lobo (1970) when he was 73; and Alfred Hitchcock’s Family Plot (1977) came out when the grand master was 77.

But the very next generation of filmmakers suffered a significantly different fate. Take Don Siegel. In 1976, following a string of successes with Eastwood, the 64-year-old filmmaker was riding high enough to land directing job for what would be John Wayne’s last film, The Shootist. But a mere three years later, it’s not clear whether his dream project, Escape from Alcatraz (1979), would have even gotten of the ground without Eastwood’s participation. Probably not, because Siegel’s last two films, Rough Cut (1980) and Jinxed (1982), were disasters because second-rate producers or stars rode roughshod over a leading American filmmaker. And Orson Welles’s fate is legendary, confined to a restaurant table as young filmmakers gloried in his company while he languished, unaided, in their industry.

Merely as an act of creative survival then, Eastwood’s longevity is inspiring.

But Eastwood does more than merely survive, as even a cursory viewing of Blood Work shows; he stretches his talent and enlarges his palette. The structural resemblance of the new film to Dirty Harry and Sudden Impact is striking. Once again, Eastwood plays an independent-minded cop, this time FBI agent Terry McCaleb (a name nicely reminiscent of "Harry Callahan"). The movie opens with McCaleb on the trail of a serial killer, "The Code Killer," who’s been taunting McCaleb with clues left with the agent specifically in mind. This mano-a-mano chase irks local cop bureaucracy (embodied by LAPD detectives play by Paul Rodriguez and Dylan Walsh), though McCaleb (typically for Eastwood’s cop characters) does turn out to have inside ally, an L.A. Sheriff’s detective (a sexualized character this time, played by Tina Lifford).

At the end of the movie’s first sequence, McCaleb spies the Code Killer, gives chase and, in the process, suffers a massive heart attack, though not before getting off a few rounds and at least winging the killer (whose face remains unseen). The film dissolves to two years later, when McCaleb is accosted by Graciela Rivers (Wanda De Jesus). McCaleb has just had a heart transplant and Rivers declares that it’s her murdered sister’s organ ticking away in the now retired agent’s chest. Because of that, she says, McCaleb has incurred a debt: The LAPD has stopped working on her sister’s case, and McCaleb must take it up.

The vengeance-seeking sister, of course, is right out of Sudden Impact, where she was played by Sondra Locke. That’s not the only similarity, though, between that nearly surreal, crime thriller and Eastwood’s newest variation. Sudden Impact used ocean water as a backdrop nearly whenever Locke’s character appeared, a harbinger of uncertainty and loss of control, with its violent climax finally set on a long amusement pier.

In Blood Work, seawater plays a prominent role again. This time, McCaleb himself lives on a boat docked at a Long Beach (CA) marina – and again, ocean water will feature even more prominently in the final violent confrontation. The ground under McCaleb’s feet is literally never steady underneath him.

That would be a glib metaphor is it was in fact a metaphor at all, but it’s not. It’s part of an entire vision. Blood Work is built around the whole idea of non-distinction, that is, the lack of obvious measuring sticks, physical or moral. The hint of a rolling sea under McCaleb’s feet is merely a note in a chord that begins with the movie’s first shot, a helicopter view of a Los Angeles neighborhood at night. The point isn’t that it’s Los Angeles, or a neighborhood, or that it’s even night, so much as that right from the start, the darkness prevents the image from forming into the usual pattern of vertical, horizontal, or diagonal patterns. There’s no frame of reference because, as we look at the screen, there’s practically no frame at all up there, just darkness punctuated by a few random points of light.

As he investigates Gloria’s murder, McCaleb finds himself running into variations of this dark or watery non-distinctiveness again and again. The movie – which is based on a novel by Michael Connelly and has a script by Brian Helgeland – is set throughout Los Angeles, in nooks where lots of people live, but where movies are rarely shot. There’s a factory in Canoga Park in the north San Fernando Valley. Eastwood shoots the action there so that the industrial plant never gets situated in any larger context; all we see are driveways, offices and shop floors that don’t seem to lead anywhere in particular. When McCaleb visits a potential witness in the desert, the screen doesn’t fill with a picturesque, colorful vastness. Instead, we get at what the inhabitants of the northern Antelope Valley live with, asphalt roads that twist through hills of scrub, and dusty hills that close off and potential vistas. Even the distinction of isolation is denied in Blood Work.

This lack of distinction is at the heart of the movie’s moral drama. McCaleb may be a cop, he may hang out with cops, but the two people he most closely connects with – by his own admission – are Grace’s killer and, to a lesser extent, Graciela. All three of them are willing to kill and the only thing that separates them, the tiny little distinction, is his or her reason for it. Grace’s killer is psychotic or evil, depending on how we see the world; Graciela is moved or deranged by grief, again according to our worldview. But what moves McCaleb to the point where he would be willing to kill – and kill in a world where there are no obvious distinctions, where even the ground under his feet sways with every borrowed breath he takes? That’s why the climax, when it finally comes, occurs with the sea and the darkness obliterating every external measure and the very notion of stability.

There’s some hoo-ha in the movie involving McCaleb’s semi-mystical empathy with Gloria, a brief vision in which he sees the dead woman’s last moments. This may or may not be residue from the book, but it’s played way down. So for that matter, is the technical end of McCaleb’s heart transplant. The retired cop does have to go in to a clinic for treatment and we do see the ugly scar on his chest now and then.

But Eastwood play’s McCaleb’s physical ailments less as post-operative crises than as the ineluctable consequences of aging. Mostly, McCaleb is on the verge of exhaustion all the time, he’s forgetful, apologetic, and upset to discover that he’s more confused about life no than he’s every been.

This is what links Blood Work with True Crime. The earlier film, though it was nominally a suspense film, recalled Hawks’s El Dorado (1967), with its frequently comic emphasis on physical ailments and late-afternoon romance. Then, too, Eastwood’s newspaperman, aside from wanting to save an innocent man on death row, was also worried about his dwindling status in what was recognized as a man – a husband, a father, and a professional.

Blood Work takes all that a step farther. Its tone isn’t mournful; it has that tight-lipped drumbeat of action and suspense we associate with Eastwood’s detective movies. But the shadows of life continue to lengthen and so does Eastwood’s gaze. Luckily – for us – he’s got a camera to bring to bring along with him.