The clergy tell us to condemn the sin and excuse the sinner, a practice which may make for fine piety, but not a compelling or persuasive film. Or so it seems from Auto Focus, the latest from cinema’s most persistent Calvinist, Paul Schrader. Based on a true-crime book, Schrader’s latest simply depicts an uninterrupted, downward arc of sinfulness ending in a violent death in a Phoenix motel room, a site Schrader unmistakably suggests (perhaps rightly), is the Gateway to Hell.

The clergy tell us to condemn the sin and excuse the sinner, a practice which may make for fine piety, but not a compelling or persuasive film. Or so it seems from Auto Focus, the latest from cinema’s most persistent Calvinist, Paul Schrader. Based on a true-crime book, Schrader’s latest simply depicts an uninterrupted, downward arc of sinfulness ending in a violent death in a Phoenix motel room, a site Schrader unmistakably suggests (perhaps rightly), is the Gateway to Hell.

Describing the movie’s ending doesn’t ruin any surprises since the it’s based on the well-known, scandalous, and unsolved murder of TV star Robert Crane. A former disc jockey who achieved popularity in "Hogan’s Heroes," an unlikely sitcom set in a World War II German POW, Crane was found shot to death in the aforementioned Arizona motel room surrounded by evidence suggesting a wild sex life. As it turned out, Crane, along with a friend named John Carpenter, had for years been videotaping sexual encounters with scores of women he met as he toured the western half of the country with a dinner theater production. Carpenter had been as sales rep for companies pioneering the lightweight video cameras that would in a decade or so, become fixtures in the homes of American families. But, when he started pressing them into the hands of celebrities in the late 1960s and early ‘70s – with the blessings of his employers – they were still novelties.

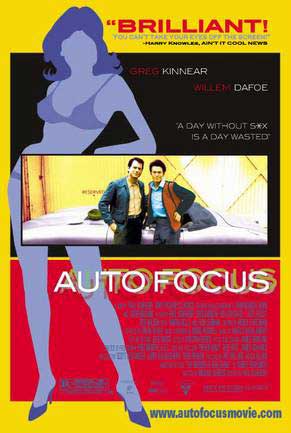

Schrader, as you might imagine from the director of American Gigolo, Patty Hearst, The Comfort of Strangers and Light Sleeper, disapproves. All these movies are, to one extent or another, cautionary tales about the danger of falling in with bad company, as is Auto Focus. The unworthy companion is Carpenter, played by Willem Dafoe at first with a smidgen of self-control, which is gradually overtaken by a facial, if not vocal, satanic burlesque.

But Carpenter is a minor Mephistopheles skirting the edges of the frame, crooked fingers reaching out to snag his companion and escort him to the underworld. The central focus is the man keeping the bad company, Crane. In Auto Focus, Schrader goes one Calvinist step beyond presenting us with his usual naïf who has fallen, spiritually unprepared, into the mire of sinful circumstance. He paints Crane, who is played by the glib former television host Greg Kinnear, as nearly conscienceless and consciousnessless. Furthermore, the implications of the title – with its evocation of preset visions, and perhaps futures – are born out by Crane’s actions, which never deviate from a mechanistic, or foreordained path. Watching the movie, there’s no reason to think that we’re watching anything but the progress of one of John Calvin’s un-elect, one those hapless humans overlooked by their creator (or Creator), untouched by grace, and doomed from the cradle to the jaws of hell.

This is a remarkable formula for drama: All powers of self-determination haven’t even been wrested from mankind. They’ve never existed in the first place. Only Schrader’s God can determine the future of his characters, and he seems to have done that a long time ago, but he’s certainly not in the movie anywhere.

Some observers have made much of the fact that Schrader has two lighting schemes for the movie, one sunny and one dark. The sunny bits are reserved for Crane’s supposedly "nice" side, his home life especially, while the dark sequences are reserved for the bachelor pads and motel rooms where his sinful assignations occur. This is an insult to Schrader, who while philosophically offensive, is a better filmmaker than that.

The essential element of his style is the rigidity of his frame, an approach that at least has the virtue of backing up his vice, the obsession with predestination. That rigidity makes itself felt not just in the firmness of the frame lines, but all through the compositions, horizontals and verticals, and in many elements of the set design. It certainly is present in his sunny home, where he lives with his first wife, Anne Crane, and their children.

Crane’s relationship with Anne, and with a second wife, Patricia (who played a character on "Hogan"), might suggest to some that perhaps Schrader isn’t all about predestination. After all, their argument might run, both these women try to pull their husband back from the brink. Isn’t this a suggestion that free will and predestination, or fate, coexist? Not really. Take, for example, a priest the Roman Catholic Crane asks for help during a late-night cup of coffee at an LA restaurant. Shocked when Crane confesses he’s been playing drums after hours in strip clubs, the priest quickly invites to join a church combo and then flees the scene. At best, the clergyman has no answers; at worst, he abdicates his responsibilities.

The wives are no better. The first Mrs. Crane is a shrew. When she discovers her husband’s substantial collection of pornography, she only berates him. Rita Wilson, who plays Anne Crane, acts out these scenes so harshly, and is made up and costumed in such an exaggerated manner, that she looks clownish. Obviously, she’s failing her husband, probably by not giving him the type of sex that would keep him happy. Similarly Patricia Crane (Maria Bello), was once her husband’s adulterous lover; she can’t make any claims on his morality once he starts cheating on her.

Nearly all the women in Auto Focus look terrible. Period clothes, hair styles, and make-up are heightened to the limits of grotesquerie. There aren’t that many sex scenes and the swift cutting keeps physical exposure to a minimum, but Schrader doesn’t need that much time to make sex appear odious in the extreme. Watching his brief scenes of couplings, the word "rutting" comes irresistibly to mind. Equally irresistibly comes the thought that the filmmaker regards women as an occasion of sin.

But somehow poor Bob Crane was fated to have these people around him. The movie leaves us no other choice but to assume that long ago God put them all in his path deliberately and then forgot about it. Crane is locked in – literally in Schrader’s tight boxes – and can’t get out. No divinity remembers him, no mercy exists in the universe to pardon him. There’s no murder mystery here. There’s no mystery at all. Schrader’s God done him in.