David Gordon Green’s first feature, George Washington, left the young director pegged as a disciple of fellow Texan Terrence Malick, a tag likely to stick thanks to his second film, All the Real Girls. Clearly, this bucolic tale of love and break-up, though radically different in tone and mood, evokes comparisons with Days of Heaven.

David Gordon Green’s first feature, George Washington, left the young director pegged as a disciple of fellow Texan Terrence Malick, a tag likely to stick thanks to his second film, All the Real Girls. Clearly, this bucolic tale of love and break-up, though radically different in tone and mood, evokes comparisons with Days of Heaven.

There are deeper questions over the resemblances Green’s newest bears to other films from other eras, but let’s not let his film get lost in the meantime, because All the Real Girls is a highly distinctive, and nearly distinguished movie. It’s a contemporary rural romance, rich in atmosphere, canny though quiet in its social delineations, and necessarily eccentric in its forms of characterization and speech.

That eccentricity is crucial because the movie’s classic narrative might nudge an audience into prejudice. All the Real Girls tells a familiar story of a country lothario who falls for a girl who has come home from the big city – or a boarding school, anyway. She returns his affection but, out on a brief weekend jaunt, sleeps with a new acquaintance. Horrified that she would break the chaste bond between them, the young man, previously a love-‘em-and-leave-‘em sort, recoils from her, and demands that somehow she repair their soiled love.

Green wrote the movie’s screenplay with Paul Schneider, who plays Paul, the 22-year-old reformed playboy of a small, rusted-out North Carolina mill town. While the movie’s enormous achievements lie in its images and performances, there’s no doubt that most audiences are going to get hung up on the dialogue. Green and Schneider have cobbled excessively ingenuous lines that continuously startle the listener into readjusting his or her ears.

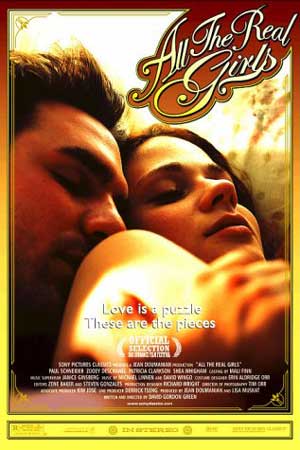

The movie’s opening image, for example, is a beautiful widescreen composition of Paul and his 18-year-old love, Noel (Zooey Deschanel – more about her soon), in semi-silhouette and loose embrace, standing in a ramshackle backyard transformed by the night into a romantic envelopment. Paul and Noel are cooing at each other, but in slightly exalted, semi-lyrical way. Paul asks Noel what she’s thinking, and she replies that she’s looking at a wooden bucket, thinking of how it reminds her of how full her heart is of love for him.

We can take a lot from that image beside the dialogue, although typically aurally-inclined audiences to disregard what they see for what they hear. And that slightly weird lyricism continues throughout the film. Paul’s romance with Noel becomes an issue between him and his best friend Tip (Shea Whigham). Tip’s also Noel’s older brother, and he is sure that Noel’s destined to become just another notch on Paul’s six-shooter. They fight, and as Tip stalks away, he cries out that Paul’s not his best friend anymore, "not even top ten." It’s a strangely childish-sounding line for a young man to sound.

The contrived tic is difficult to fathom. Green and Schneider may well consider it a form of rural naturalism. Or, it could have been a way of keeping the actors from slipping into routine caricatures of country folk, the kind of accent-mongering that afflicts Hollywood-driven projects about the South.

It feels similar to the juxtaposition between the extraordinary imagistic eloquence of silent films and the crude utilitarianism of their intertitles, particularly when those titles are supposed to articulate the voices of country folk.

Green’s whole project does summon memories of bucolic romances of the1920s, as does Malick’s Days of Heaven. But if the older filmmaker’s work suggests a more downbeat Sunrise, complete with the Murnau-ian Manichean contrasts of night and day, All the Real Girls is suffused with a brighter, more Borzagean optimism. It’s not that Green is making a specific reference to Frank Borzage or any other silent filmmaker. But consciously or not, he has appropriated a way of looking at, and hence feeling about, life, that recalls an unalienated viewpoint of an earlier era. If you look at his film, with its images of an encompassing landscape, its integration of homes (and garages and rusted factories) with countryside, grace notes of water and flora or of growth and decay, and the easy presence of people within every environment, you get the sense of a detachment without separation. There’s a deep bond between Green and his characters and their world, even though he knows its their world and not his.

The movie’s old-new feel is embodied by its beautiful leading lady, Deschanel. For the film’s first half, she wears her brown hair long and thick, and together with her big eyes, they suggest a timelessness. We catch her and Paul after they’ve already begun their romance, so we take it as natural. But when she leaves him for the fateful brief trip away, several things conspire to shake our faith in their privileged naturalness.

One of them is simply a telephone. Noel is at party at a modern woodsy hideaway, a chic timbered lodge where her boarding school education makes her comfortable in a way her hometown friends never could be. She’s talking, in close-up, on the phone to Paul and the sight of a modern telephone receiver in her hand is jarring, a sudden intrusion of brand-new modernity that reminds us she’s been hanging out in the land of the old and second-hand.

These differences continue when Noel gets her hair cut short, which radically changes her appearance, though not her out-of-time beauty (Deschanel has a kohl-eyed look). Tresses and beauty is what’s carrying All the Real Girls along: Deschanel’s hair, her eyes, her midriff in one scene. Not just because of their beauty, but because of the drama that Green’s direction gives to that beauty and all the beauty in the movie.

Green makes a huge emotional investment in his second film, an investment he hedged somewhat by dealing with children in George Washington. His expanded that investment with shrewd collaborators – Schneider and Deschanel – as well as a large cast that expertly, but vulnerably follows his lead. Sometimes the movie trips over its own tongue, but it’s still a fascinating venture.