One destroys, the other doesn't - well, let’s hold on a minute. It’s oversimplifying to say that within the partnership of director Spike Jonze and screenwriter Charlie Kaufman, that Jonze handles all the destruction and Kaufman all the creation. But in the yin/yang of artistic production, it’s Jonze’s enthusiasm for mayhem that counteracts Kaufman’s queasiness in the face of the necessary wrecking ball.

One destroys, the other doesn't - well, let’s hold on a minute. It’s oversimplifying to say that within the partnership of director Spike Jonze and screenwriter Charlie Kaufman, that Jonze handles all the destruction and Kaufman all the creation. But in the yin/yang of artistic production, it’s Jonze’s enthusiasm for mayhem that counteracts Kaufman’s queasiness in the face of the necessary wrecking ball.That tension was the vitality that ran like an underground torrent beneath Being John Malkovich. In Adaptation, it bursts through the surface and becomes the overt subject. Or nearly anyway.

On the face of it, Adaptation appears to be a semi-autobiographical account by Kaufman about his struggles to adapt "The Orchid Thief" to the screen. "Thief" was a book-length version of an article written for The New Yorker by the highly gifted and stylish writer Susan Orlean (confession: I used to know the enchanting Ms. Orlean when we both worked at the Boston Phoenix a decade and a half ago). The article and book were centered on John Laroche, a colorful Floridian who snuck into state and national wildlife reservations to steal protected and but highly valuable orchids. But Orlean used Laroche and orchids as a jumping off point for other stories and some personal musings.

In real and reel life, Kaufman was hired to adapt it for the screen, but ran into trouble after he realized that the book’s discursive style didn’t readily lend itself to screen treatment.

The crucial point about the movie is that it "appears" to be semi-autobiographical. It starts in what looks like a pretty realistic manner: Over the opening credits, we hear "Charlie Kaufman’s" voice (actually the voice of Nicolas Cage, who plays Kaufman), berating himself neurotically for his slovenly eating habits, work habits, his big fat ass, and various other faults. We see Charlie dissed on the set of Malkovich. From there, we cut to a Hollywood restaurant where Charlie is coming to an agreement with an amiable executive (Tilda Swinton) to make the film.

The realistic tone continues with Charlie’s conscious failures to pick up on romantic hints from his girlfriend (Cara Seymour), a turn of events which increases his self-loathing; with encounters with his outgoing but intellectually dense twin Donald (Cage again), who has decided to become a screenwriter himself; and with frustratingly unsuccessful attempts to begin writing.

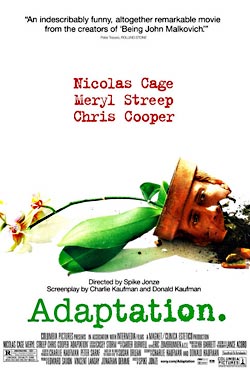

Interspersed with these scenes are flashback sequences from "The Orchid Thief" starring Meryl Streep as Orlean and Chris Cooper as Laroche. These take place three years earlier than the main action, and show John making a foray into a swamp, getting busted, and meeting up with Orlean for the first time. For all the stress Charlie is encountering at the typewriter, these scenes seem perfectly natural and engrossing. Yet, whenever we cut back to the "present," when Charlie is insisting to someone that just including action like that would be superficial. It wouldn’t get to the heart of the book, which lay in Orlean’s asides and tangential musings.

Generally, this set-up will be altered by two large movements and one overwhelming fear. The two apparently segregated storylines, that is, the Charlie-adaptation struggle-Hollywood story and the Orlean-Laroche-Florida tale, will merge and become one narrative. The relationship between the brothers will become ever more complicated as Donald writes a successful action-film screenplay that Charlie loaths, but which Donald sells for a small fortune. Donald insists Charlie go to a seminar led by his "guru," the real-life Robert McKee (played in the movie by an explosive Brian Cox), a figure Charlie holds in great distaste, to say the least.

The great fear is Charlie’s. He’s afraid that in adapting Orlean’s book to the screen, he’ll fail to do justice to it. That in creating one piece of art, he’ll destroy another. The inevitable create/destroy cycle terrifies him – or at least immobilizes him.

It’s not clear that anyone connected with the film actually chose this as a theme. There’s an awful lot of talking in the movie about the different types of adaptation. There’s the natural type of adaptation, as in the way different types of orchids and insects have adapted in ways that insure each other’s survival. How the book must be adapted to the screen. How Charlie must adapt to Hollywood and how he must adapt to his girlfriend’s sexual expectations if he’s ever going to have an adult relationship.

Of course, the movie’s called Adaptation, so it’s fair to think that Jonze and Kaufman were determined to make all sorts of Statements with Irony and Self-Reference. There’s certainly self-reference. The film’s opening credits announce that the movie is written by Charlie Kaufman and Donald Kaufman, but in reality there is no Donald Kaufman. When Donald describes his action movie to Charlie, the latter sputters over its lack of plausibility. For one thing, it involves a character with multiple personalities who plays three different main characters in the movie. How, Charlie asks, could such a character manage to be in different places at the same time in different guises at crucial passages in the plot? But of course, that’s just what John Cusack’s character was able to do in Being John Malkovich. Donald also mentions the benefits of trick photography, and the visual tricks in Adaptation that put Cage together with himself in the same shot are mind-bogglingly persuasive to the eye.

So Charlie has done just what he snickers at Donald for attempting, but Charlie is Donald anyway. But what does that amount to, aside from an in-joke? How many people in the audience are going to get the reference anyway? For that matter, how many people are going to know that while the movie Charlie excoriates himself for being fat, the real Charlie is skinny?

Are these in-jokes, or are these ways Kaufman had of reminding himself that he was writing fiction, not autobiography. Splitting himself in half, and altering his physique, could be handy writer’s tricks, ways of harnessing the imaginative part of his brain.

We could also look at the film from another angle. All these interpretations assume that everything about Adaptation was a matter of intention. Filmmakers, perhaps because so much preparation is involved in getting a production underway, are more certain than any other creators, that what they’ve done has been done "on purpose." But the purpose of finishing a movie is not the same as the intention of creating a piece of art. One you can control; the other you can’t.

To take in all of Adaptation, we have to look at the 600 pound gorilla who never gets mentioned, director Spike Jonze. A director’s contributions can be as elusive as the nature of film itself, but they are just as determinative, too: Pace, vision, scale – things of life. And Adaptation is a movie about life. Yes, it’s about adaptation, but it’s also about creation, and about how you must destroy before you can create.

John Laroche destroys various selves (turtle collector, mirror collector) before he fashions his modern self (orchid thief). Susan Orlean destroys Laroche as a person in order to resurrect him as a journalistic peg for thoughts on life. Charlie has to kill off Susan Orlean as a thoughtful writer in order to make her a suitable heroine for a movie about swamps, guns and midnight thievery.

Of all these people, it’s only Jonze, standing above them all, who has to, and who does, relish the job of destruction. Because he has to begin the movie be destroying Charlie, but setting him up as a foolish person with his camera, with his staging, with his direction of Cage. Jonze has to bring verve to the action sequences, an unrelenting enthusiasm to anything remotely resembling destruction, even if it’s a cutting remark at a dinner table. Without this continual destructive drive, the film can’t even begin to move towards a resolution.

Though Charlie Kaufman created a mirror image for himself in Donald, Jonze is better reflection for the writer – that is, the same but all turned around. There’s an inside joke in that that I wonder if the two thought of. Jonze’s real name is Spiegel, which is the German word for mirror. What do you know about that?