If you’re an LA resident or just someone interested in California’s largest sprawl, and don’t read website LA Observed (www.laobserved.com), you should. It’s a fascinating digest of breaking Los Angelesiana, journalism news, and footnotes overseen by the site’s creator, the estimable Kevin Roderick (estimable because, among other things, he’s linked to these pages).

If you’re an LA resident or just someone interested in California’s largest sprawl, and don’t read website LA Observed (www.laobserved.com), you should. It’s a fascinating digest of breaking Los Angelesiana, journalism news, and footnotes overseen by the site’s creator, the estimable Kevin Roderick (estimable because, among other things, he’s linked to these pages).

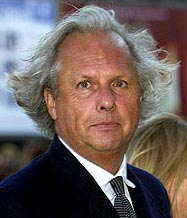

Over the weekend of May 14, Roderick posted several links. The first of them involved an article by LA Weekly show biz expert Nikki Finke, who reported that both the New York Times and LA Times were rushing to get competing stories into print. The stories concerned the relationship of Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter to Hollywood, specifically how the editor has received financial payments from a Hollywood bigwig. This on top of social perks he gleans from his mag’s Oscar party, even as he continues to oversee its gushy, pseudo-sophisticated coverage of movie-making. Roderick later posted to the early stories the papers ran on the weekend, stories that highlighted a $100,000 payment Carter received from Brian Grazer, producer of A Beautiful Mind, a payment that sounds out of whack compared to Carter’s contribution to the movie. Apparently the editor suggested the original book, which was serialized in Vanity Fair, would make a good movie (not that it did).

Although we’re used to reading about millions, tens of millions, and even hundreds of millions of dollars when we read about the movie industry, that shouldn’t deter us from regarding $100,000 for what it is: An enormous amount of money. How many Americans make even half of that in a year? In most parts of the country, it’s enough money to buy a nice house outright. You can put a child through – or mostly through – a four-year private college for that much. And it’s more cash than most people retire with. And we’re just talking about the U.S.A.; heaven only knows what it would buy – or how much good it would do – in other parts of the world.

Moreover, there’s the question of what the payment is for. No doubt there was an absence of a direct quid pro quo. Carter didn’t run story A because he got payment B (at least that sounds like too crude, and too blatant, an arrangement). But he did tighten the binds that already connected him and his magazine to businessmen who see access to the magazine’s pages and covers as avenues to riches.

Don’t make the mistake of assessing Vanity Fair coverage solely for its impact on movie ticket sales. Measured in those terms, its influence is minimal. But Vanity Fair decides what’s hip for a many of the people who inhabit Hollywood. And what’s hip in these circles is necessarily what’s for sale. So if an actor appears on the cover, his/her price might go up. If an Academy member reads a movie is “important” in Vanity Fair’s pages, they might be more likely to vote for it at Oscar time.

That Carter could be unaffected by his swell relationship with people who cut him $100,000 checks beggars belief. It’s not as if Vanity Fair star and movie profiles aren’t already compromised before they even appear. A phalanx of publicists stand guard over stars and productions. To pass them by, one has to prove oneself “trustworthy,” i.e., committed not to air dirty laundry. Naturally, entertainment journalism isn’t investigative reporting, but even a personality profile can be done candidly. Look back at the movie coverage in Esquire and Rolling Stone back in the early 1970s, before those publications went journalistically belly-up in the manner of a chastised dog.

Carter doesn’t have to interfere with his writers to earn his money. I, for example, give treats to my dog even when I don’t expect him to perform some trick in return. I’m just rewarding him for his general good behavior. Carter only has to make sure that his magazine keeps up what it’s doing and no doubt there will be more checks in the future.

Some people (see the comments section at LA Observed) are trying to pass off the Carter payment as somehow trivial, as beside the point in an area of journalistic and business ethics that’s already mottled gray. Baloney.

Of all the untrustworthy attitudes (cool, fashionable, radical, etc.), that one can affect, the most self-destructive and false is cynicism. Self-destructive because it demands that one minimize immoral behavior as “the way of the world.” False because it is usually born, not of vast experience, but of fear of an expansive grasp of life.

One cannot compartmentalize the part of oneself that makes or accepts dubious payments from the rest of one’s moral self. In Thomas De Quincy’s famous formulation, committing murder puts you on a slippery slope that will invariably end with bad manners. One can’t trust a businessman who raids the larder to pay off an editor and one can’t trust an editor who accepts, or requests, the money.

It’s a sign of the times that this point needs reaffirming.