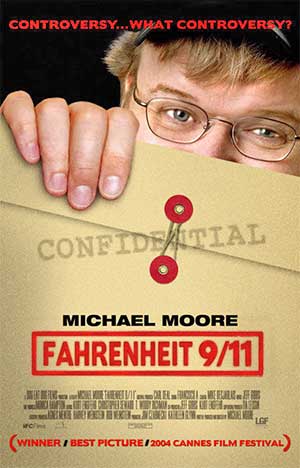

Determined to prove that there’s no such thing as bad publicity, Jack Valenti, the head of the Motion Picture Association of America, has prevailed upon the distributors of Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11 to change a quote in the movie’s ad. The quote, as it happens, is from Richard Roeper, and read in its original form, “Everybody should see this movie.”

Determined to prove that there’s no such thing as bad publicity, Jack Valenti, the head of the Motion Picture Association of America, has prevailed upon the distributors of Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11 to change a quote in the movie’s ad. The quote, as it happens, is from Richard Roeper, and read in its original form, “Everybody should see this movie.”Valenti, as head honcho of the organization that doles out the film ratings, says the quote was inappropriate given that Fahrenheit 9/11 was rated R. Not everybody could see the movie, according to this risible argument, unless they were over 16 or accompanied by a parent or guardian. The distributors acquiesced and the quote has been altered to read, “See this movie.”

See this movie, indeed. It’s interesting to note that the R rating came about for two reasons. One, the ratings board found the salty language used by some characters (mostly soldiers) offensive for young ears and, two, the images of dead and wounded Iraqis, most of them women and children, were considered too raw for young eyes.

Of course, teenagers are exactly the people most likely to trade in obscene banter; never try to out curse an adolescent, because he/she could have your ears steaming in minutes. Likewise, with their air of inviolability, teenagers are notoriously immune to images of others’ suffering. I remember sitting with two classes of Catholic schoolboys watching Alain Resnais’s remorselessly painful study of the Nazi death camps, Night and Fog, and the general response being unstudied indifference. I’m not saying that there wasn’t any boys who were affected, or that all the boys weren’t affected in some dim, distant orbit of their souls. But no one turned away from the screen in shock, as, now grown men, they might each do today.

Valenti and the MPAA, however, don’t seem to want Moore’s film to touch even the unlit recesses of the adolescent consciousness. If we put the issue of “bad” language aside, we’d have to consider this the most overt sort of political censorship, as there is no war footage in Fahrenheit 9/11 that is any more terrible than what was on the nightly news during the Vietnam War.

Of course, two different Bush administrations have gone to an awful lot of trouble to make sure that the nightly news never broadcast any such imagery from the Middle East. After Bush I came in for criticism for being too heavy-handed in its policy of news control during the war in Kuwait, Bush II came up with its brilliant replacement strategy: Embedding. Reporters (most using the grand titles “journalists” and, my favorite, “correspondents,” even though they don’t correspond) thought that by being forced to travel with a specific company of soldiers they were actually getting the real story, when in fact they were being controlled and, if anything, kept from the story. There were no shots of dead or wounded Iraqis because newsmen and women were kept from them – as they happily admitted.

Moore, in an almost literal way, is wandering “off reservation” by finding this footage and putting it in his film, alongside interviews with American soldiers that don’t make them look bad (only human), but don’t follow the Pentagon line, either.

Fahrenheit 9/11 is not the sort of film I particularly enjoy reviewing and, since no one pays me to run this website, I don’t. It’s not a film whose style or technique requires elucidation; it’s themes lie plainly on its surface and do not resonate below. Mostly, though, it’s the sort of movie everyone seems to have an opinion of and it hardly seems worth adding another one to the pile. I thought Roger & Me was a bad film and Bowling for Columbine a somewhat better one that seriously overreached and, like its predecessor, was fatally condescending to its subjects.

What’s remarkable about Fahrenheit 9/11, though, is how much people want to shut it up, effectively by keeping people away from it. To do so, they use the same tactics they accuse Moore of using, i.e., trying to string together a few stray facts into a large tapestry.

The only time Moore takes a flyer in the film is when he implies that because of years-long business ties with the Saudis, the Bushes father and son tanked on the terrorism front. The business ties themselves are well-known by this point and were described, for example, in Republican writer Kevin Phillips’s book, American Dynasty. Fahrenheit 9/11 spins a theoretical conspiracy out of those facts, but it’s the only section of a several-segment film that uses that technique.

A lot of the movie is savagely satirical, as Moore depicts what he considers the inadequate intelligence and leadership qualities of George W. Bush and the pusillanimity of the Democratic leadership. The movie reaches an emotional climax when Moore examines the social and ethnic backgrounds of the vast majority of soldiers, spends some time with veterans, and meets up with the mother of a soldier who has served in Iraq.

You have to wonder what has caused all the hyperventilating over the movie. I keep coming back to the pictures of the women and children killed by missiles and bombs. There is nothing for sheer horror as the sight of a little limb with a tiny bone sticking out from a gash, or a young woman’s sheared-off leg. Watching those images, we have no choice but to associate ourselves with them; those acts were done in our name, even if they were done against our wills. You can either accept that association, or rebel against it. To rebel against it means, in part, to keep down the numbers of those who accept it.

Louis Althusser said, “Ideology has very little to do with ‘consciousness’ – it is profoundly unconscious.” No doubt objecting to the word “everybody” doesn’t seem like an ideological act. But surely it is the most profound sort of one.