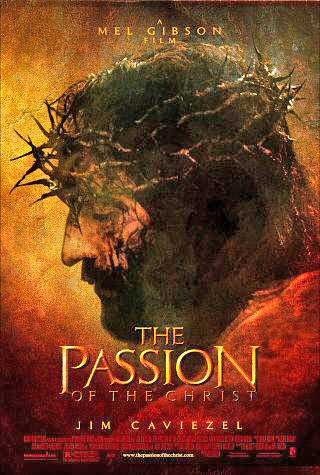

What did Mel Gibson miss about the Passion that gives the lie to his claims of fundamental truth? Specifically, for pre-Vatican Council II truth? For that, we must step into a time machine and travel back, back, back to the 1960s, a few years before the council meets…

What did Mel Gibson miss about the Passion that gives the lie to his claims of fundamental truth? Specifically, for pre-Vatican Council II truth? For that, we must step into a time machine and travel back, back, back to the 1960s, a few years before the council meets…

As you walked into Sacred Heart School, where your correspondent spent his grammar school years, you were met by a statue of the Risen Christ on top of a pedestal. Bent over so that it looked down on the smallest little boys and girls who came through the front door, it was, base and all, probably only an un-unnerving eye-level to the school’s high school students (Sacred Heart was 1-12). The figure had a peaceful visage and a hand half raised in a blessing, both meant as a welcoming gesture. As we trooped by it on our way in and out of school, pupils, as we were known, acknowledged the statue with a thoughtlessly tossed-off sign of the cross meant not to honor the statue (as was drummed into our heads), but the miracle of salvation it symbolized. The statue and the ritual became daily commonplaces, as extraordinary as tying your shoes and less likely to interrupt the lees of a recess conversation.

A non-Catholic adult visiting the school for the first time might have not noticed the face or hand, but been drawn to another of the figure’s features. Worn on, rather than resting inside, the chest was a bulging red heart, entwined and gorily pierced with a ring of thorns and bleeding large drops of blood. Any student – excuse me, pupil – in the school could have rattled off the symbolism that overlay the tortured organ (“God the father out of his love for Man sent his son Jesus into the world who suffered and died on the cross and rose from the dead three days later” all without drawing a breath). But no doubt, the statue and its grotesque image, as well as a few that rivaled it in the church next door, would raise eyebrows among adherents to religions less given to the Baroque.

There is nothing quite like the impassivity of the six-year-old’s gaze, though (unless it’s the five-year-old’s or infant’s), and that unbiased but judgmental look was perfectly able to encompass both Jesus’s kindly look and his bleeding heart. The statue, Jesus, his face and his heart all existed on different planes of varying realities, but still somehow in the same world in which we lived. Some we could touch now, some we couldn’t, some we could when we got to heaven. It was our simultaneous introduction to religion and to art.

This all from a plaster pile that most adults, with some justification, would call kitsch. But it’s kitsch with a pedigree. Christ is smiling not because he’s thrilled at the sight of smudgy boys and girls clambering up the steps (well, not only because), but because he’s the Risen Christ, now fulfilled in the promise of his father. He is beyond death, beyond suffering, and ready to establish his Church. Nevertheless, the bleeding heart, and most particularly the thorns with their obvious reference to the crown of thorns worn during Jesus’s passage along his via dolorosa, refer at the same time to death, to Jesus’s human suffering and death on the cross. Easter and Good Friday. Good Friday and Easter. One with the other and never one without the other.

This is a tradition that goes back throughout Christian art and, after Martin Luther and his greater emphasis on Christ’s death on the cross, Catholic art after that. Christ’s crucifixion is but part of a process that gains its glorious ending with the triumph (over sin and death) on Easter, when Mary and her companions come to anoint Jesus’s body and find the rock rolled away and the tomb empty.

Great Christian art can contain these two impulses even when depicting only one of the events. There is a mosaic of the crucifixion at the Byzantine church at Daphni in Greece which was executed around 1100 A.D., the Middle Ages. While Christ has blood spouting from the wound on his side, the artist has depicted Christ’s body as anatomically ennobled and recumbent rather than scourged and slack, and his face peaceful. Although Mary and John the Baptist look anguished beneath him, Christ’s appearance looks forward to his Resurrection.

Over 450 years later, during the Renaissance, Tintoretto would paint his massive Crucifixion for the Scuola di S. Rocco, which takes in a vast panorama of the activities of Christ’s death. All the lamentation, pain and death associated with Good Friday are present, but at the apex of it all, the artist puts the crucified Christ’s head and his halo, so high that the top of the cross disappears out of the painting. Rays from the head spread out over all the action, encompassing it, foretelling the time – not three days off – when Christ would triumph over the grave.

For his Resurrection of Christ, Giovanni Bellini nearly divided his painting in half. Above, against a sky of emerging blue and clouds lit pink by the rising sun, Christ rises from his grave, a breeze ruffling his burial loincloth as if blowing away the last dust of the tomb. Below him, though, is a dark, more complicated landscape, with the open tomb itself and the Roman guards – who once jeered at Christ on the cross – either stunned or in anguish. One of them is, like Christ, clothed only in a discreetly place white cloth. His body -- shadowed, curled and tightened -- is in marked contrast to resurrected figure above. Clearly, the depiction of the painting’s lower half not only captures the scene around the grave at the moment of Christ’s exit, but also echoes, at least in general terms, the suffering of Good Friday.

The desire of so many Renaissance artists to capture both the sorrows of Good Friday and the promise of Easter may account for both the large number and widespread excellence of Pietàs. A Pietà depicts the moment when Mary cradles the broken body of her son, Jesus, just as it has been taken down from the cross. Compared to the epic dramas of the Crucifixion and the Resurrection, it’s a relatively quiet moment, but still one pregnant with meaning.

Obviously, the subject offers many challenges for the artist, psychologically and formally. But to look at perhaps the greatest Pietà, Michelangelo’s sculpture in St. Peter’s, is to realize the achievement is spiritual. In fact, both Michelangelo and Titian tried to sculpt or paint Pietàs for their own tombs, but failed to beat death to the finish line.

For us, who live in an age that has reduced irony to mere sarcasm, it may be difficult to realize that the power of the Pietà rests in dramatic irony. Mary cradles her son, distraught over his suffering and death, miserably confident of her loss. But Jesus’s face is peaceful, sometimes even with the trace of a smile, as if finally assured that his Passion has been successfully completed and that only the glory of god is to follow.

Easter is not a coda, an epilogue, a denouement, to Good Friday. It is implicit in Good Friday or Good Friday makes no sense. The statue in the hallway of Sacred Heart School may have been emphasizing the reciprocal thesis – that Good Friday, in the shape of the bleeding heart, is implicit in Easter and the Risen Christ – but these are two sides of the same coin.

Whatever workshop turned out that kitschy-looking statue that day – and however many more – its busy craftsmen understood an underlying truth with greater clarity than Mel Gibson clearly has. So that leaves the question, just who exactly has made the worse piece of art?