Johnnie To, just as frequently credited as Johnny To or Johnnie To Kei-Fung, or perhaps even Du Qifeng, has been making the most interesting gangster films to come out of Hong Kong for at least the last six years. Unfortunately, almost none of these movies have been shown in the United States. The Mission (1999) has been shown at film festivals, but the extraordinary A Hero Never Dies (1998) and the deft Running Out of Time (1999) have been only available on import DVDs, and then fitfully. The problem has been alleviated somewhat with Palm Pictures’s release of the delirious Fulltime Killer, a 2001 feature To directed along with his usual directing and producing partner, Wai Ka Fai. These four films are reviewed elsewhere on this site in a piece entitled "4 X To." (online soon)

Johnnie To, just as frequently credited as Johnny To or Johnnie To Kei-Fung, or perhaps even Du Qifeng, has been making the most interesting gangster films to come out of Hong Kong for at least the last six years. Unfortunately, almost none of these movies have been shown in the United States. The Mission (1999) has been shown at film festivals, but the extraordinary A Hero Never Dies (1998) and the deft Running Out of Time (1999) have been only available on import DVDs, and then fitfully. The problem has been alleviated somewhat with Palm Pictures’s release of the delirious Fulltime Killer, a 2001 feature To directed along with his usual directing and producing partner, Wai Ka Fai. These four films are reviewed elsewhere on this site in a piece entitled "4 X To." (online soon)The following interview with To (whose name rhymes with row and is pronounced with a soft "t"), took place on the morning of March 12, 2003, at the Los Angeles office of To and Palm Pictures’s publicists. To (who was born in 1955) arrived in a gray suit, a very reserved man though polite and, by the end of the interview, fairly friendly. Not trusting his own English, To used a translator, Sean Ding, who turned out to be a great help. Rather than pretend I have To’s exact words to work from, I’ve decided just to provide a transcript of my questions and Ding’s translations.

A few notes. Aside from the gangster movies, the interview refers to two other To films. One is Wu Yen (2001), a period ghost comedy, which at least used to be a favorite Hong Kong genre, though this one has a lot of gender switching. Longtime star Anita Mui stars as an emperor of China who gets mixed up with a jealous spirit and an otherwise beautiful mountain girl with a scar. The other is My Left Eye Sees Ghosts (2002), starring Hong Kong singing star Sammi Cheng as a young woman who - well the title says most of it; add some romance and you’ll get an idea.

During the discussion of the music in Fulltime Killer, To gives the ending away. You may want to skip that until after you’ve seen the movie.

Q. Because his background is not yet widely known in the United States, could Mr. To begin by sketching it out?

A. In 1973, Mr. To joined the TVB television network, one of the big television channels in Hong Kong. His first job was as a messenger. As he got more exposed to the things going on there, he wanted to be involved with production. So over the next four years, he was gradually made assistant director in the TV production department; in 1977 he became a TV director officially. In 1978 he made his directorial debut with a movie called The Enigmatic Case. Having completed that movie, he felt that he wasn’t qualified or experienced to be a real film director so he went back to the TV station and also worked on some side projects – assistant on some film production things. It was not until 1986 until he shot his second movie, Happy Ghost 3. From 1986 until the early ‘90s he made a lot of commercial movies for Cinema City, which was the most successful film company of that time. But it was in the early ‘90s that Mr. To thought of exploring films in his own style, rather than making basically blockbuster commercial movies – even though that’s not a very easy thing to do, of course, for most people. He wanted to explore his own direction. He started his company Milkyway Image and in 1994-95 he did a movie called Loving You, and that’s really the beginning of Johnny To making "Johnnie To movies."

Q. Did you deliberately enter into making gangster movies with the intention of doing them in a different style, of changing the genre in some way?

A. In Hong Kong there were trends, obviously, in the late ‘80s; John Woo’s movies started a series of action movies. After that there were the "Gamblers" movies, all of them involving gangsters. After that it there was the "Young and Restless" series, also involving gangsters, but young gangsters. For Mr. To, of course, it’s kind of weird, why would he would to tackle this genre in the late 1990s? In a way, he wanted to do something different. The rules set by the gangster-hero movies in the late ‘80s were very clear cut between black and white. There’s always a theme of restoring justice or of revenge, making the traitor pay.

For Mr. To, having seen in Western cinema an evolution of the gangster genre from the ‘30s and the Capone movies to The Godfather, and a change of style and themes, he thought it would be interesting to do something for the Hong Kong gangster genre. So for movies like A Hero Never Dies or [1998’s] The Longest Nite [To and Wai Ka-Fai produced only; Patrick Yau Tat-Chi directed] or the other movies, what he wanted to do was introduce new themes into the genre. An emphasis on fate and destiny. Or emphasis on characters; qualities of different characters, anti-heroes or [different] senses of hero. That’s what he wants to bring to these movies since the mid-‘90s.

Q. The movies explore very big variations on these themes. Especially the ones with two main characters. For example, A Hero Never Dies is very wrought up, almost a painful film, with a very strange relationship between the two characters – though they try to kill each other, they have the most honest relationship in the movie. Then you have Running Out of Time, which is like a caper film, almost lighthearted. And in Fulltime Killer, Mr. To pushes two types – the cool professional killer on the one hand and the psychotic killer on the other – to extremes. Is he having fun? Exploring how many varieties of relationships there can be between two killers or action rivals?

A. For Mr. To, there are infinite possibilities in all of the movies. For him, these pairings will never repeat. Today he’ll make a movie about this particular pair, but someday later will make something very different. For him this play off between the two characters in each pairing is a mixture of hostility versus respect for each other, this relationship where in a way they’re very close but in a way they’re so different, is for him a very romantic kind of a world. Even though the pairing is a recurring design in his movies, there’s a lot of different possibilities to play off from that. For him, even in the future, if it’s possible, he’d want to continue this pattern. But to introduce two other types of characters to play off each other.

Maybe the reason he likes this kind of a pairing is – you’ve heard him mention the titles of movies – The Sundance Kid, Borsalino – these are the movies [To breaks in and reminds Ding that he also said Babylon] – and Babylon, these are the movies he grew up on, these are the movies that he’s fond of. Maybe that’s why today he likes to continue the theme.

Q. The action scenes are so unique. Of course they have a lot of action, a lot of gunplay. But there’s – I can’t think of another word for it – a calm, a steadiness to them. The best example I can think of is the gunfight in The Mission in the shopping mall. The people are just standing there while they’re shooting. We’ll often see this in his films; it’s exciting but there’s this steadiness, as if something larger going on. I’d like to know how he achieved this control of tone.

A. He’ll answer your question based on The Mission. The shopping mall scene. Mr. To will walk you through the way he designed that particular scene. First of all, he wanted to present the characters in that scene as dancers, as almost a stage. He wanted a stage-like presentation and therefore he shot them only in still so you could see where each dancer belonged, in his position. But on more of a dramatic level, thematic level, what he wanted to communicate is really that the five bodyguards, the killers, they each had their position to guard. That’s their duty, that’s what they’re not moving. That’s the story. They need to work together, they need to protect their own position in order to make the whole team function they way it should. When he was making the movie the actors also asked the same question, why they would be standing in the same position. But when he completed the picture, everyone understood. Because each one, by holding his own ground, made up the whole for the entire team. That’s what it’s really about, these five killers might not agree with each other, they may argue at times, but when they’re put under the kind of situation that tests their job duty, they function like an efficient whole.

So basically, when he designs a scene, for Mr. To it’s not really about how to achieve a visual look. First it’s to think about what he wants to express. And for this particular scene it’s really about unity, about how these five hitmen function together. That’s how he was able to think of a visual presentation for that. It’s not about putting them together so they look nice.

Q. Still, though, Mr. To achieves great stylistic - flourishes isn’t a good enough word – high style. Fulltime Killer begins with a descending crane shot in a cemetery. Then the next scene, in the train station, begins with a descending crane shot. And the scene after that in Thailand, when we first see Andy Lau, also begins with a descending crane shot.

A. To reflect the theme of this movie. Fulltime Killer presents a world of romanticized killers. It’s not meant to be taken for real. The use of these crane shots in the movie – not just in the scenes you mentioned, but also, for example, in Singapore, these really crazy, wild crane shots… There is a standard film language where if you shoot two people you would use a specific lens so it would look real and balanced, for example. But he really went for this motion and feel, to have this really elaborate movement. In this way, it’s detached from reality. It’s not a normal perspective. He wanted everything to be moving the whole time, the mise-en-scene and everything, that eventually the movie itself detaches itself from reality and everything is almost floating by. It gives you a world that is not so real but more make-believe. That’s the kind of world he wants to put forth in this movie.

In The Mission, you know the world is a romanticized world but that’s the only movie that he does not move the camera. It still offers a stylized world. It’s really not about camera movement itself, it’s really about the movement of the entire movie… It’s really about the overall design of the movies rather than just camera movement alone.

Q. It seems that every director who is, say, an artist, has an instinctive choice of lens. Mr. To’s choice appears to be a shallow, wide lens to go for the widest viewpoint possible. Does he agree?

Q. It seems that every director who is, say, an artist, has an instinctive choice of lens. Mr. To’s choice appears to be a shallow, wide lens to go for the widest viewpoint possible. Does he agree?

A. Mr. To of course tends to what you said, the wide-angle lens. But for him, the odyssey is to create new things and try to be different. In future projects he would like to use tighter lenses given the appropriate subject matter. He wants to use lens at the opposite end of the wide-angle lenses and do something different so he doesn’t repeat himself.

Q. Back to Fulltime Killer, I’d like to talk about the use of "Largo al factotum" and Beethoven’s Ninth. Of course, they work as distancing devices, but they’re also exciting. What’s behind their use?

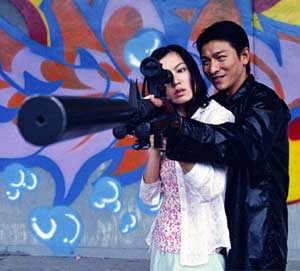

A. For Mr. To, of course, the music creates a detached, distancing effect. But more than that. The music accompanies Andy Lau’s character, the flamboyant killer, and his tragic life and career. In a way, what happens to the Andy Lau character as the failed Olympic shooter and a failed assassin at the end, is a very tragic thing. And he chose this music because to turn Andy Lau’s character and what he goes through into a real tragedy. And the music itself takes you into the past, it takes you away from the moment of now, when it’s kind of tragic. That gives the tragic life of Andy Lau’s character a more stylized and more romanticized kind of tribute. Accompanied by the fireworks at the end, for example, even though Andy Lau’s character slowly dies, but the fireworks accompanied by the music brings out something of Andy Lau’s character where for a brief moment he has seized that glory that he’s always been after. That something that does not happen, he gets a brief taste of it at the end. That music is meant to bring out that part, almost a glorification of his tragic death.

Again, the music, most importantly, is because he does not want anyone to think of anything as real, but as a world detached from reality. A stylized world.

Q. To talk about his actors for a minute, they give very precise performances. I’m thinking of in The Mission, Francis Ng; he makes very subtle facial changes. And we see over a number of films, when we see how different his performances are, Lau Ching Wan, he’s actually giving quiet differences in performances, as well as big ones. So I was wondering how Mr. To works with actors, to what extent he dictates small movements, to what extent he leaves it up to the actors.

A. For Mr. To, there are two kinds of actors and two ways of working with them. The first kind are very creative, whose acting skills are very established. [This actor] knows how to figure out his own performance. With this kind of actor, Mr. To will not ask him to deliver a performance, but rather just explain to the actor the mood for a situation and what he wants to characters to convey through the camera. Then he will leave it up to the actors to figure out their performance. For the other kind of actors, who are less experienced, whose performances may not be very stable, then Mr. To will give very specific orders of what to do. For example, "Hold a gun, look left, look right." He will very specific on what he wants. So those guys can deliver the kind of performance the director wants.

But most importantly, whether its group A or group B, what Mr. To wants from an actor is somebody who is committed to the project. Somebody who can be a part of this project. Somebody involved. He wants everybody to be involved in the creative process.

Q. Is Lam Suet someone who is in a lot of his movies?

A. Yes, of course.

Q. A favorite actor?

A. I’ll give you a little background information first about Lam Suet, he has a very interesting history. He actually has been working with Mr. To for more than 10 years. He used to be a set runner, a unit manager, he was somebody who worked behind the scenes. It was in the mid-1990s he graduated to become a leading man under Mr. To’s direct choice. He was in movies like [1999’s] Where a Good Man Goes and, of course, The Mission. Today, we’re happy to say, he’s a professional actor in Hong Kong. He’s no longer a set runner or anything.

For Mr. To, he thinks Lam Suet is not a creative actor. But he is committed, he is dedicated to acting. When the director tells him what to do, he will do his best to achieve that result. So he’s obviously somebody Mr. To is used to working with.

Q. Is there a star he has a particular affinity for? It’s fairly obvious, but I’d like him to say it.

A. It’s Lau Ching Wan.

Q. He’s an excellent actor. As you know, Hong Kong movies are very popular with a group of people in the U.S., but I don’t think he’s well known with that group.

A. [Sean Ding for himself] Unfortunate, but maybe soon.

Q. Why have you made a ghost comedy, Wu Yen, and a ghost romance, My Left Eye Sees Ghosts, lately?

A. For Wu Yen, in terms of casting, there’s not many movies in Hong Kong that give female actors a good chance to show off their talent. And after Heroic Trio, Mr. To thought it would be interesting to do an ensemble piece to test the market. Of course, Heroic Trio didn’t do very well in Hong Kong. Wu Yen is a comedy and is a more commercial movie and would have done better than Heroic Trio. In terms of story, it’s more of a fairy tale. It’s using a fairy tale to reflect a modern mentality: In Hong Kong, there are people who go to China have a secret mistress. So it’s a satire [Johnny To breaks in: It’s very common!] But also to reflect the traditional position of women in China.

As for My Left Eye Sees Ghosts, first of all casting-wise, Sammi Cheng has done a lot of movies with Mr. To and other filmmakers, movies about office workers; urban, white collar comedies. It was really time, commercially speaking, to do something different, to change her persona. At that time in Hong Kong movies about ghosts were quite popular. At the same time, Mr. To really wanted to tell a moving love story, not like Ghost, but hopefully with the same power.

Q. What is the condition filmmaking in Hong Kong right now? The last I heard, the financial structure was not good.

A. The Hong Kong film market is obviously not in its boom days any longer. Right now, you can say the Hong Kong film industry is in recession. In the past there were foreign markets in Korea, Taiwan and other places. Today these markets have been taken over by Korean films. Hong Kong films just don’t have the appeal they had in the past. Because of the diminishing markets obviously investors are now more cautious when it comes to putting money into films. But at the same time, Hong Kong movies have, at least for now, have gotten through the worst phase in its history. 1998-99 were probably the worst; a very difficult time for filmmaking. Now things are picking up slowly. It’s not like Hong Kong’s recession has passed. When Bruce Lee passed away in the ‘70s, Hong Kong films for a while didn’t have a sense of direction; many films were not being made.

But right now, the optimistic side of things is that sometime within the next year or two, the mainland market will open up. Because right now Hong Kong films are still considered "import films." In the future the mainland will open up as a local market. That’s where the potential lies.

Q. A huge domestic market.

A. Huge, huge.

Q. Like here.

A. [Johnnie To directly] Yes.

[Sean Ding] In the last two months a lot of good Hong Kong movies did very well at the box office. Movies like Infernal Affairs, Golden Chicken and Hero did much better than their foreign competitors, so we see support for Hong Kong movies and they may very well do well in China in the future.

Q. You mentioned Heroic Trio [laughter from Johnny To and Sean Ding] and you know, this is a huge cult film in the United States and it’s in Irma Vep. You say 1995 is the starting date for "Johnnie To movies" and Heroic Trio was made in 1992. Is it a millstone round your neck; would you rather never hear of it again?

A. Mr. To likes the film, he enjoyed making the film. The regret is that unfortunately the box office in Hong Kong was not so good, so he was a little bit upset with that. But it’s a movie that he enjoyed a lot.