In the summer of 1977 or 1978 (in any case, sometime after Star Wars came out, as becomes obvious as you read through), I drove out to Los Angeles from Chicago. At the time I was either enrolled or in the process of dropping out at the University of Chicago, where my major intellectual interest was Doc Films, at the time still one of the country’s intellectual centers of auteurism. It was a center bereft of a journal, though, and I was thinking of reviving Focus, a long-folded publication Doc had once put out.

In the summer of 1977 or 1978 (in any case, sometime after Star Wars came out, as becomes obvious as you read through), I drove out to Los Angeles from Chicago. At the time I was either enrolled or in the process of dropping out at the University of Chicago, where my major intellectual interest was Doc Films, at the time still one of the country’s intellectual centers of auteurism. It was a center bereft of a journal, though, and I was thinking of reviving Focus, a long-folded publication Doc had once put out. At the same time, I had developed a critical fascination with Vincente Minnelli, an American director who suffered from woeful indifference from most – though certainly not all – American critics. Although his films were almost equally divided among melodramas, comedies and musicals, only Minnelli’s musicals attracted any attention. General intolerance of melodrama had left Minnelli’s best films (Some Came Running, Home From the Hill and, especially, The Bad and The Beautiful) languishing. They still languish for that matter. Minnelli’s melodramas haven’t achieved anything like that stature of Douglas Sirk’s, perhaps because Minnelli’s are Mediterranean and Freudian whereas Sirk’s are Northern European and Marxist. Unfortunately for Minnelli, American and English critics don’t like their melodramas to be too melodramatic. Anyway, back in the Seventies, Minnelli’s lesser musicals (An American in Paris) tended to be overprized, while his stylish and emotionally complex bits of perfection (The Band Wagon, Cabin in the Sky, even, believe it or not, Meet Me in St. Louis) were semi-forgotten. (That situation has at least markedly improved). As for the comedies (Father of the Bride, Designing Woman), well, forget it.

Maybe it was that Minnelli managed to spend more than two decades at MGM without major problems. MGM had a deserved reputation for being an artistic strait-jacket, but that reputation applied largely to the years 1924-1949. Minnelli’s years (1940-1943 as musical number specialist; 1943-1963 as director) overlapped those briefly, but while he was assigned to his share of studio dreck, the vast majority of his important projects (regardless of budget), proceeded unhindered by corporate malfeasance (and much less than they would in today’s Hollywood). If Minnelli could be happy at MGM for so long, so conventional American critical thinking went, he must be a hack.

To heroic me, in my very early 20s, this was an outrage. Using a mobile camera in a way that consistently reflected a character’s state of mind, Minnelli had spent years building a cinema of neurotic obsession. But it wasn’t a cinema of stasis, but of crisis and growth. The tension in a Minnelli film is dynamically jagged or, if you prefer, jaggedly dynamic. This seemed an obvious conclusion to me and, as I soon discovered, to others as well. The American critic Stuart Byron, had used On a Clear Day You Can See Forever as the starting point for a brilliant essay exploring Minnelli’s themes. The critics and filmmakers surrounding Cahiers du Cinema had connected with Minnelli starting in the Fifties. While no one critic’s interpretations coincided directly, all agreed on the way Minnelli’s films began with characters who had succumbed, or were succumbing, to an imprisoning neurosis (which could be very, very funny, or quite tragic or sexually frustrating) and then found their way to a cathartic liberation.

An interview with Minnelli, who was in his mid-70s at the time of my Los Angeles trip, seemed perfect. And getting in touch with him was easy. I simply went to the Directors Guild, paid $5 dollars for its directory, and there, under the "Ms", with a list of his credits, was "Vincente Minnelli", his home phone number, and his address. I called him right away and a voice, which I recognized instantly as his (I had seen Minnelli make an appearance at th Chicago Film Festival two years earlier) answered the phone. A minute later, I had an appointment to interview him at his house, catty-corner from the Beverly Hills Hotel.

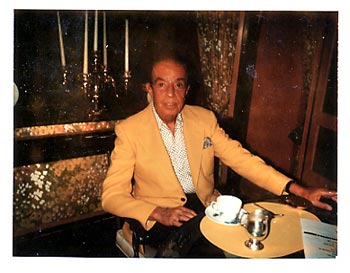

Minnelli’s home was a relatively modest, mission-style house. The front room, I remember, was painted a kind of overwhelming yellow, not particularly bright, but of a shade I now recognize as omnipresent in so-called Southwest design. But what was mostly impressive is that nearly every surface – couches, tables, piano – was covered with framed photographs and art books. Minnelli came down dressed as you see him in the picture and was extraordinary kind and gracious to an unknown and somewhat scruffy (I did my best but it was the Seventies, I was in my early 20s – you know) young man with an unhealthy interest in film.

I’ve decided to print the entire interview in transcript form for a few reasons. First of all, this is the internet, and it’s supposed to have the room to get out all kinds of raw information unedited. Maybe later I’ll cut it down.

But also, this was the first interview of any kind whatsoever I’d ever conducted and I really stunk at it. I was never really sure when Minnelli was going to ask me to leave; it was clear from the way he dressed and the cars parked in his driveway that he probably had a fairly busy social life. I had a lot of movies I wanted to get to, and once we got halfway into something, I thought maybe we should skip onto something else before we run out of time.

Mostly, though, at the time I sat down with the filmmaker, I had something I wanted to prove: That Minnelli had an artistic preoccupation with psychoanalytic theory. Of course, I was the preoccupied one in this situation, preoccupied with proving my theories about Minnelli to Minnelli himself. I want the questions to show this. It was an extremely important side to the bullish – not to say mulish – way I conducted the interview.

For the most part, Minnelli responded to these clumsy thrusts as did most members of his filmmaking generation. Reflexively, he’d assert that Hollywood filmmaking was a collaborative process and that he always depended on the contributions of writers, cameramen, designers, etc. Yet, Minnelli was quick to say that he would con writers into re-writes, demand particular cinematographers for particular jobs, or fight with art directors over design. And when I’d suggest that over the years he had depended on the contributions of particular writers (Alan Jay Lerner) or cinematographers (Harry Stradling), Minnelli would dismiss the suggestion almost out of hand as overstating their creative importance.

Most satisfying is that, in the middle of discussing something else, Minnelli would suddenly declare his devotion to both Freud and surrealism. In keeping with that general attitude, Minnelli talked with some ambivalence about Yolanda and the Thief, his most blatantly bizarre, dreamy movie. The significance of his ambivalence is that, in every other forum I know of in which he’s mentioned the movie, it’s been to dismiss it as a mistake altogether. Clearly, the film is more important to him than he generally admitted.

Finally, a note about the lack of plot synopses. The interview and this introduction are long enough. If you are curious about the movies, you can rent nearly all of them, if not all. If you want a quick plot summation, you can always turn to "Leonard Maltin’s Movie & Video Guide."

Oh, yeah. I never did get Focus going again. So no one has ever read the interview until this internet posting, about 25 years on. Minnelli died in 1986 at the age of 83 and the obituaries largely referred to him as the director of An American in Paris and Gigi. No shame in that. But it’s time to start engraving his name on the Pantheon.

Q. [tape starts up] "more general questions about general themes in your films and then maybe get to more specific"

A. Sure, okay fine, just ask the questions [laughs].

Q. Your films seem very psychoanalytically oriented, in that the main character, at least after a certain point, is in a position of neurotic obsession he has to work his way through. This seems very consistent from The Cobweb (1955) forward. I’m sure it’s very conscious, but I was wondering why this became so particular at this time. Or did it?

A. I don’t know. It’s intuitional, I guess. It’s the story that counts. I work with the writer on the story. Having started as a designer I have a lot to do with settings and costumes, because I think they relate to the story and character, explain it.

Q. Your films do rely much more on visuals than dialogue. You say you rely on the writer. You’ve worked with Alan Jay Lerner [1918-1986] many times. I’m interested that On a Clear Day You Can See Forever (1970) is so different as a film than as a play. One of Daisy’s personas, the American one, was dropped, and the movie depends on the persona Melinda. Was Lerner at the point where he knew what you wanted?

A. Yes. We worked carefully on that. I felt that was what was wrong with the play. It was white wigs and writing with feathers which gets to be very boring. I wanted to make it Regency, because the world was more inviting. That’s particularly why we changed it. Then I wanted to come in on a climax where she didn’t know what was happening and it was explained later on. Whereas it couldn’t matter less in the play.

Are you sure you won’t have coffee? I always have coffee without sugar, you know. Just cream. Barbra Streisand didn’t take sugar towards the end [of production]. Then she saw in an antique store a tray and coffee pot and a few mugs, but no sugar [bowl], it was missing [laughs]. So she inscribed it with, "You’re the cream in my coffee."

Q. On a Clear Day seems like such a very personal film of yours, and I was wondering if you would consider it one of your more personal projects, one that you were happier with from the beginning,

A. It was mystical and Lerner has been interested in that since he was a child. He was trying to say something, I dug into the story and that was what came out.

Q. In your autobiography [I Remember It Well, 1974] you mention that one of the films you were interested in doing but unhappy in the way it was presented was Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1962)…

A. Yes, I preferred to have it in the original war [World War I] because times were different then. Argentina was very Nazi. With the Second World War, all you could do was have [the protagonist] as someone who blows up bridges.

Q. Well, it seems if you’d been developing the theme where an individual must develop a free will, then you do place it in a political context for the first time, or a pronounced political context for the first time. The whole film seems to be concerned with what is a free will worth without a political context.

A. Yes, well, he starts out as a playboy and couldn’t care less about politics – he gets involved because of a woman. From then on he’s part of the action.

Q. Another film I’d like to talk about is a very early one, Madame Bovary (1949). If some films can be regarded as a summing up, this one seems to be an anticipation. There’s really no liberation for Madame Bovary…

A. No! She fantasized everything! Her dreams were so much more realistic than reality. She dreamed so big and wanted everything to be beautiful. And everything was hideous, starting with the farm, the convent and all that. Disillusion about her husband.

Q. In your autobiography again, when you talk about Home From the Hill (1960), you talk about the operatic sense of the boar hunt. That operatic sense also seems present in the ballroom scene in Madame Bovary, almost a building hysteria.

Q. In your autobiography again, when you talk about Home From the Hill (1960), you talk about the operatic sense of the boar hunt. That operatic sense also seems present in the ballroom scene in Madame Bovary, almost a building hysteria.

A. Yes, that’s the one time that the dream came up to the reality. She saw herself as wanted and beautiful; the belle of the ball, so to speak. Then it ended bitterly. Illusion.

Q. Your camera style has always been – and you mention this right off when you talk about Cabin in the Sky (1943) in your autobiography – is you went for a very fluid camera that moved a great deal. This seems linked to your thematic preoccupations; it’s a peering style.

A. I was very influenced by the movies of Max Ophüls, who moved the camera all the time. That made much more sense to me than to catch each composition as it appeared.

Q. Did you ever meet Ophüls?

A. No, by the time I got over there, he was quite sick and died shortly thereafter.

Q. Well, since we’re on the subject right now, would you feel any empathy, as opposed to just admiration, for any other directors?

A. Von Stroheim. I lived in New York, so I saw the European movies much more than the domestic ones. I was influenced by them a great deal.

Q. You mentioned [dir. Jacques Feyder’s] Carnival in Flanders [La Kermesse heroique] (1935) and [cinematographer] Harry Stradling (1902-1970)…

A. He just happened to be there…

Q. In France at the time…

A. He was an American. He happened to be in France. He got his start in France and England. When I came to work with him – I describe that in the book – he didn’t have any artistic sense about him. He would stumble through the thing; he’d say, "Anyone up there? It’s dark down here." I’d think, "Oh, Christ." But when I saw the rushes, they were fantastic.

Q. You must have developed quite a relationship, since you worked until quite recently [On a Clear Day You Can See Forever].

A. Oh, yes.

Q. You also worked with John Alton, who must have been quite different to work with.

A. Oh, yes. I got Metro to let me use him on Father of the Bride (1950). Up till that time he’d just done B movies off the lot. The cameramen hated him. I don’t wonder, because he was so egotistical. He didn’t mean to be. When I was on the sequel, Father’s Little Dividend (1951), we hadn’t shot the ballet yet, and I insisted on him shooting it, because he would take chances. It needed somebody who would take enormous chances and do things that were crazy.

Q. You seem to take many chances in the painterly aspects of your films, even when it comes to the aspect ratios you use. You’ve mentioned the Flemish influences on the interiors in Brigadoon (1954) and the time you spent on copying Sem in Gigi (1958).

A. Colette (1873-1954) had written about actual people in Gigi. She considered it one of her minor things, not to be compared to Vagabond or Cheri. It’s had a life of its own.

Q. Gigi was another collaboration with Lerner…

A. That was written for the screen.

Q. There was a play, but you didn’t like it.

A. The play went to farce. It used the mother. [Colette] had worked on the French movie [Gigi, dir. Jacqueline Audry, 1948 or '49] and that was a farce also. But she created the character, Honoré, Chevalier [would] play [in the Minnelli version]. It was right to use Chevalier.

Q. In terms of your themes, Gaston (Louis Jourdan) is the figure undergoing the most change. In a way, he’s the protagonist and Gigi is the goal he works towards. It’s been suggested that you look upon Gigi and Brigadoon as perhaps fairy tales or wish-fulfillments with happy endings.

A. That [the ending of Gigi] is supposed to be quite abrupt, because he’s the last man to marry anybody. But in Brigadoon it’s a surprise that he goes back to Brigadoon, reach back into his consciousness and create it all over again out of time.

Q. In your comedies, with a few exceptions, people seem drawn to their antitheses. In The Reluctant Debutante (1958), an upper class girl to a jazz drummer; in Designing Woman (1957) the sportswriter and the designer; in Goodbye Charlie (1964), well,…

A. That’s a real fairy tale!

Q. It’s not only the lady killer becoming a lady but becoming attracted to a former friend, I wondered, do you depend on this structure to build your comedy?

A. No. I seem to be drawn to things that actually happen. For instance, Meet Me in St. Louis (1944), Sally Benson was writing about her own family in St. Louis at the time. The Long, Long Trailer (1954) actually happened and the man wrote a book about it. Father of the Bride, same thing; a banker wrote that who had never written anything else. Designing Woman was written for the screen. I just got back from Deauville and Greg [Peck] was there. He sat behind me and they ran an early picture of his, To Kill a Mockingbird (1962). He leaned over and said, "Why don’t we run Designing Woman and get a few laughs in here! This is a dour subject!"

Q. You mention in the autobiography that he was an under-player but you brought out his lighter quality.

A. He sparkled.

Q. I’d like to discuss The Bad and The Beautiful (1952). In the book you seem, with good reason, to be puzzled by the reaction, which was so mixed. You quote Bosley Crowther as complimenting it and then saying it just didn’t seem to turn out that well.

A. It was very successful. Mostly I liked the picture very much. But it was the point of view of three people. When I wanted to do this picture, instead of Lili [dir Charles Walters, 1953; musical set in France starring Leslie Caron], which I’d already done [referring to just completed An American in Paris] Dore Schary [head of production at MGM, 1948-1956] said, "What do you want to do that for?" Even my agent said, "That’s the story of a heel." Ahh, I didn’t think so. He’s got to have an awful lot of charm. He just is crazy about movies; he’d kill his mother to make a good movie. He’d have to have such charm. Well, Kirk Douglas has strength, you know. It doesn’t have to be there, it’s there. So he played it completely for charm. When he came off a scene he’d say to me, "I was very charming in that scene!" We played it completely for charm when he stepped on people’s necks. But he was always correct. The director wasn’t ready to do that fine picture, but he was with the producer’s help. The writer’s wife was driving the writer crazy. So he was correct in all those things. But he had the strength to go through with it and hurt the people he loved.

And he did get the after-film blues. It’s a let-down. "What the hell is so important about that

?" We work so hard, and then suddenly it stops.

Q. To talk about The Bad and the Beautiful almost inevitably brings up Two Weeks in Another Town (1962). I saw you in Chicago two years ago at the film festival and you mentioned that the final cut of the picture was not…

A. No the man that was in charge of Metro in New York recut the picture. He took two whole sections out. He ruined the orgy and took out a long scene that Cyd [Charisse] had with a reporter in a bar in a hotel. She explained why she was the way she was. Without those scenes, the picture was ruined. [Producer John] Houseman was in Europe at the time so I immediately wired him and talked to him on the phone. He came rushing over but it was too late. The negative had been cut. There were too many prints in the theaters.

Q. Is there any way at all to see your cut?

A. No. I don’t think so. Too much water has gone under the bridge at Metro.

Q. The car scene, where the character Jack Andrus, Kirk Douglas, drives down the hill reliving the experiences of the past, recalls Lana Turner’s in The Bad and the Beautiful…

A. Yes.

Q. Stuart Byron wrote a long essay on On a Clear Day You Can See Forever, I don’t know if you ever saw it…

A. No! I didn’t!

Q. He says this is an example of the cathartic scene you can find in so many of your pictures. Now, structurally, do you look for this to put this in your pictures.

A. No, no. It’s always the story that interests me.

Q. How much…

A. What does the story mean, how do the characters fit into it, how are they eloquent enough to talk about it in the way it should be talked about.

Q. When you’re presented with a story when a project begins to develop, do you go in for extensive re-writing.

A. Yes, we work together, the writer and I. I con him or charm in into re-writing an awful lot.

Q. You seemed to have a brief problem with writers during The Pirate (1948), when they wanted to reverse the situation, and make Gene Kelly a pirate who wanted to be a good actor rather than an actor pretending to be a pirate.

A. [Loud laughter] Well, that wasn’t a problem because everybody was surprised by that! We couldn’t wait to see what they had done, they said, "Look at this, it’s so funny, so terribly funny." We sat there with gloom on our faces and the next day we hired someone else.

Q. That is one of the most beautiful pictures I have ever seen. How much trouble do you have to go through to achieve…

A. It’s exotic. That happened on an island in the West Indies in the 1830s. In those times the islands were free ports, so you had a mixture of Creoles, Spanish, Chinese, French, and so forth. So it was a natural to be exotic.

Q. Do you allow for improvisation.

A. I prepare as much as possible. I allow an area for improvisation because the chemical things actors bring to stories make it not work. So it has to be worked upon. Lust for Life (1956) was completely done over while in Europe. Fortunately, John Houseman is a marvelous writer and he sat in on so many story conferences. He worked with Welles, you know, and he’s a marvelous man.

Q. I’d like to ask about Lust for Life. Is that picture presented the way you cut it and finished it.

A. Oh, yes.

Q. There was no interference.

A. It follows the pattern of his life absolutely.

Q. In the essay that Byron wrote, he uses a phrase in describing the end of Van Gogh, "the joyful suicide of release." Do you see it as that?

A. No. It was very sad, because his madness caught up with him and he couldn’t go on. Just couldn’t go on.

Q. So you would say he didn’t achieve a breakthrough in his personality?

A. He sold only one painting and for something like 35 francs. And his brother was an art dealer. The big reward came after he died.

Q. You don’t feel that in the sanitarium he achieved tranquility.

A. When we went to that sanitarium, which was the actual one he was incarcerated in, the man read – very literally and very straight – [unintelligible] he’d had a bad time. I glommed on to that. I said, "John, we have to write it that way."

Q. I would like to talk a little bit about Yolanda and the Thief (1945). First of all, how did the studio react to surreal sequences? Did it stand them on their heads?

A. Well - yes. It wasn’t successful with the audiences. It got its money back and showed a small profit, but any picture did in those days. [MGM production unit head and producer Arthur] Freed (1894-1973) did that and Freed brought me together with [Madeleine author Ludwig] Bemelmans (1898-1962). It was the kind of thing that Bemelmans would write: A con man posing as a guardian angel – which shocked most of the critics at the time. Nowadays it wouldn’t matter if he were a murderer.

But surrealism is present in most of my pictures.

Q. Would you care to elaborate?

A. Sure. In the Thirties, when I was in New York, I did the first surrealistic ballet in a show of mine. The choreography was done by Balanchine. Dali was the great painter then and surrealism was a way of life.

It followed a long time later – Freud, dreams, the inconsistency of dreams. It struck me that it was the sensation of life. I used it whenever I could.

Q. In Yolanda, the whole film has an airy, dream-like quality where you’d be willing to believe, or that it is not illogical to believe, that Fred Astaire could be, a guardian angel.

A. She was raised in a convent with nuns and so forth and didn’t know how to take care of her vast wealth and prayed to her guardian angel for guidance. And he [the con man] overheard her.

Q. How did Astaire react to the exoticism.

A. He was marvelous about it. He liked it very much.

Q. In An American in Paris, you would say the surrealism came in the end.

A. Well, that’s a ballet of emotions. He had lost his girl and that mattered terribly, he was a painter. It was all mixed up together.

Q. You mentioned Freud. Have you read a great deal by him?

A. Yes.

Q. When working with a writer do you bring up Freudian interpretations and motivations.

A. No, I stick to the point of the story.

Q. In the films with Gene Kelly, did he choreograph all his dances?

A. Yes. The ballet was a collaboration with both of us. I seemed to be the moving factor in that. But sometimes he would be. So it went. I did many films with him and we always got along wonderfully because we both knew there 20 ways to do a scene.

Q. Do you mean one of you say, block out a scene and the other would…

A. No, it would be more specific. We’d be more specific. We’d say, "Get the crowd over there and do that little…" While he was blocking out the choreography of the first part, for instance, I took the assistants and got the running through the traffic. The camera is doing this and so forth and the light is changing.

The Pirate is surrealism and so, in a curious way, is Father of the Bride.

Q. I love the walk down the [church] aisle.

A. It all stuck to what had happened the night before in that miserable scene in the rain. His walking down the aisle is his inability to get there.

Q. You have such a personal interest in the set design, your sensibility of it. Did you find yourself having much trouble with [department chief] Cedric Gibbons of the [MGM] art department.

A. No. Cedric Gibbons was the grand cardinal of the art department. He would be in meetings. And not with the designers themselves, because they were great art directors. But with the interpretation of Cedric, because finally he did things a certain way and I insisted on not doing it that way. Finally he let me alone.

Q. But there was a little working out for a while.

Q. But there was a little working out for a while.

A. Yes. Naturally on Cabin in the Sky (1943).

Q. Do you have the idea for the sepia tones on that film?

A. No, that was Arthur Freed’s idea. Have you seen it that way?

Q. Yes.

A. I haven’t seen it that way in a long time.

Q. Just briefly, the musicals. Musicals are "supposed" to be joyous, bouncy, exciting and brash but a lot of yours seem meditative. The beginning of The Band Wagon (1953), for example, when Astaire gets off the train all by himself.

A. He was such a sport to do that and play the part of a man whose career was dying, when his was never better. What was the question again?

Q. Instead of being happy and bouncy, it starts…

A. Well, I consider, that those things – even farce – should be played for blood. Then it’s funny. But not if you’re going to poke the audience in the ribs and say, "Watch this." It’s got to be real.

Q. Jack Buchanan made so few films, I was wondering how he came to appear in The Band Wagon.

A. That was a very difficult thing to do. The character was obviously Orson Welles and the kind of people who do the things he does – Shakespeare one night, "Oedipus Rex" the next, then a farce by Oscar Wilde. We had a hard time deciding on who to do it, and thank God we got Jack Buchanan because he was marvelous.

Q. Do you know if Welles ever saw it?

A. I know Welles but I never talked to him about it.

Q. Would you care to talk about the conditions under which you did Tea and Sympathy (1956)? Was that something you very much wanted to do or was it a project that just came by.

A. It was the first film on homosexuality, but it wasn’t real homosexuality, it was the way a boy [John Kerr] thought people looked on him. We had great trouble with the Johnson Office [de facto industry censor]; they kept looking over our shoulder and worrying about it and biting their nails. They made [Robert] Anderson, who wrote the play as well as the screenplay, put on the prologue as well as the epilogue, where she [character played memorably by Deborah Kerr] had died to atone for her sin. He hated to do it.

Q. What kind of pressure would the studio use to accomplish that? Just say, "You do it or we’ll get someone else to"?

A. Oh, no, no. They’d knew we’d have a lot of trouble with the Johnson Office and they let us alone. Our troubles were all with the Johnson Office.

Q. Tea and Sympathy is very compressed. The scenes are very charged, there’s a lot of movement even in dialogue scenes. Did you emphasize that on purpose?

A. Noooo… I learn new things all the time.

Q. Again, what I mentioned before about progression through illusions. I’m referring to the scene with the town whore, where he can’t make it with her.

A. Oh, yes, yes.

Q. He’s unhappy with the image he presents, he’s trying to abandon it for another one that’s equally false…

A. But he’s in love with Laura [Deborah Kerr] at that point. He can’t make it with the whore because the cheapness of her, the squalor bothers him. That scene was not in the play.

Q. Yes, I read the play. Whose idea was it?

A. Partly mine. I had a hard time convincing Sherwood. But then he became adjusted to it and fought like hell for it.

Q. Even when you deal with a specific framework like the Caribbean in the 1830s or the France of Flaubert – and this is a description you used about Brigadoon – "you enveloped it all with romantic mist." [About Brigadoon composer Frederick] Lowe said how if he didn’t Scottish music he relied on Brahms. Even though you draw on these historical realities, let’s say, you tend to place it in, not a dream world, but your own very personal world. Do you just look at these historical situations as inspiration?

A. I tried my best to make that look as if it happened in Scotland in the days when the Scottish people were very primitive.

Q. How do you feel about never having done Green Mansions after all the work you seem to have put into it? [The movie, a fantasy about an enchanted bird girl and a hunter, was eventually directed by Mel Ferrer starring Audrey Hepburn and released in 1959].

A. I’m terribly glad now. When you have a girl who dresses in spider web clothing – which is woven by a spider – and sits in trees and talks bird languages, you aren’t sitting pretty, you know? But I went down to Venezuela and spend a few weeks going through jungles. It’s fantastic looking.

Q. Home From the Hill (1960) and Some Came Running (1959) seem to go together in that they examine American society very closely. Both are concerned with the individual, one with the artist. In both there really has to be a killing. Shirley MacLaine must die and Wade seems to have to die. In Home From the Hill, I wonder if you consider there’s a homoerotic relationship between George Peppard and George Hamilton.

A. No, it never occurred to me. Because they were, as far Hamilton was concerned, they were brothers, and he wanted the other recognized. And Peppard was used to it [a lack of recognition] and didn’t care.

Q. What would you consider your most personal films, the ones that you were able to bring the most to, the ones you had to adapt yourself least to.

A. I always liked the Van Gogh story because I was terribly involved in that. We shot that in all the real places where Van Gogh worked. His letters are reflected in that, the five volumes of letters he wrote to Theo. He was eloquent and discursive on a subject in the affirmative and then he would turn right around and knock it down in the negative. And that character is like Emma Bovary. That’s the type of character I like the best.

Q. Now the mirrors in the Madame Bovary ballroom scene; those must be very consciously placed to emphasize her narcissism.

A. Yes. She looks up and sees herself with men and officers asking her to dance. That is the dream she recognizes. I use mirrors all through that. The cracked mirror in the horrible establishment she rents in Rouen. The thing she looks into to put her make-up on in the last scene. In the convent. People don’t realize how many mirrors there are in that.

Q. Same for Gigi.

A. No. Madame Bovary is where I started out to use them to help the story.

Q. You use, particularly in Brigadoon and On a Clear Day, blue sky a lot. Particularly at the end On a Clear Day they’ve been inside for the whole film almost, then all of a sudden, there’s the blue sky. Then there’s such a contrast between the smoke-filled bar Gene Kelly leaves to return to Brigadoon. You hold back on the use of exteriors purposely?

A. Not particularly. It’s just the way the story goes.

Q. In Yves Montand’s office, are you focusing on the window in his office in any particular way in developing the scenes in any particular way – in terms of having it opened and closed in human relation terms.

A, Not consciously.

Q. It’s almost cliché right now to say in your films that the décor reflects the personality? [I was going to say of the characters, but Minnellli cuts in]

A. Yes, but people don’t realize that the décor, what they hold and the surroundings, tell an awful lot about the character. That’s what I’m concerned with, the character.

Q. In Band Wagon at one point, we’re in a house. One room is red, another room blue, another room is green – there’s a monochromatic effect. Is that a stylistic shock?

A. No, no. I use colors to bring fine points of story and character. It’s intuitional there.

Q. You’d much rather work in color than black-and-white.

A. Oh, yes.

Q. Do you feel like you’re restricted in terms of depth of focus in color or that you can more than make up for it with the color itself and its shadings.

A. Color can do anything that black-and-white can.

Q. On a Clear Day You Can See Forever seems such a summing-up and such a change from other films – say Some Came Running, where the Frank Sinatra character doesn’t want to place himself above his friends, yet doesn’t want to be trapped by them. And this whole conflict of who he and trying to work himself out. And it takes someone else’s death – as in so many of your films it seems…

A. Well, originally, Frank was killed in that. It was his idea to kill Shirley, which I thought was marvelous.

Q. Do actors frequently contribute that much?

A. Oh, yes. I listen to them very carefully. And if they’re wrong, I tell them they’re wrong. We discuss that an awful lot.

Q. Robert Mitchum must bring an lot more than he cares to admit.

A. He’s a dream to work with. He’s so helpful. He worked with George Hamilton. It was only his third picture. He’d made Crime and Punishment U.S.A., which was an arty picture, so he needed a lot of work.

Q. Once Sinatra works his problems out in Some Came Running or Kirk Douglas does in Two Weeks in Another Town, they’ve done it more or less by themselves and mostly through observation. But in On a Clear Day, the doctor and Daisy work together, unconsciously. It’s the first time two characters achieve liberation mutually in one of your films.

A. Don’t forget that she’s unconscious when she makes those statements and he has to draw it out of her. And he’s amazed at how many lives she’s lived.

Q. You put that picture of Einstein sticking his tongue out on his desk.

A. That was Yves Montand’s favorite picture!

Q. It seems you're mocking him, saying he has a mock scientific objectivity, that he can’t deal with people as people. In his classroom, when he talks about people he has a diagram of the brain, he’s reduced it to such cold facts.

A. That’s a good observation, but he’s a wonderful doctor. That’s one approach.

Q. As far as Daisy being unconscious, there’s the great line Streisand gets to deliver, "He wasn’t interested in me, he was interested in me." When she does realize this, when she does begin to accept her ESP, this whole mystical thing, the whole film seems maybe allegorical or almost on the level of a parable. The way they’re going to be married in 2038 in their next lives. Do you feel this was a conscious moving away [on your part].

A. No, it was the way it was written. Lerner had read all these books and followed the fantasy as he saw it completely. I didn’t subscribe to it, not at all.

Q. Lerner and you must think a great deal alike or share world views.

A. Well, I appreciate Lerner, he has such a wonderful mind. We argue, trying to convince each other.

Q. The ending of Four Horsemen is almost apocalyptic and it seems like the whole world is being destroyed. Is that the impression you were trying to convey?

A. Yes, the senselessness of war.

Q. You have Julio in such personal situation at the beginning of the film when everything just concerns the family. Then it moves towards a more political context, then, at the end, the political context has been brought back down to a personal level again.

A. In which way does it come to the personal?

Q. When there are just two of them in the room and the Nazi character says to Julio, "You did this? You?"

A. He asks because he’s only known him as a playboy.

Q. Not to dwell on Four Horsemen too much, but you dwell on the figures riding through the sky a great deal.

A. They were there in the original.

Q. Is that a source of worry to you, though, that people might not be able to accept those images, that they want more naturalism?

A. That’s the reason I had the andirons in the fire with the same figures. Otherwise Julio wouldn’t be able to have seen them.

Q. Now Goodbye Charlie; was that your first picture away from MGM?

A. Yes.

Q. What were the circumstances?

A. At first I didn’t want to do it because I thought the idea was vulgar. But the idea of a man being killed during an episode of love and coming back as a woman started to impress me more and more and more.

Q. The casting – Debbie Reynolds has that kind of…

A. I thought [Tony] Curtis was wonderful. It should be Marilyn Monroe, a woman with all that charm. And a man who was a he-man, a man who was now burdened with all those things he had always loved.

Q. Did George Axelrod [who wrote the source play] write the screenplay?

A. No, Harry Kurnitz.

Q. Axelrod wasn’t involved?

A. No.

Q. Now, Cabin in the Sky(1943). How in the Forties did someone go about making a [Hollywood] picture that was all-Black.

A. The only picture that had been all-Black was made about 15 years before that, [King Vidor’s] Hallelujah. It was a wonderful story, the Devil and an angel of the Lord fighting over a man’s soul. It was beautiful on the stage and I had seen it on the stage before I came out [to Hollywood]. So I loved it immediately.

Q. It’s so non-condescending, say compared to Green Pastures (1939). But you wonder why more didn’t come of it. Why Lena Horne didn’t become a bigger star, for instance.

A. According to her book [Horne wrote two memoirs, In Person (1951) and Lena (1965)], I did the first numbers before I became a director. They were carefully so they could be taken out bodily in the South. I think the time hadn’t come when the Blacks were stars.

Q. Just a social condition.

A. Yes.

Q. I’m sure you’ve read the Cahiers du Cinema group’s analyses and the way they’ve said your characters are continually making a choice between a fantasy world and a real world in your films.

A. Yes [laughs] – I don’t know why!

Q. So you would disagree with that assessment.

A. Well, it’s marvelous that they… When I first went over, it was during Lust for Life, I was surprised to find out there was a Cahiers du Cinema, when they gave a luncheon for me. Lo and behold they’d written about me every so often. I felt that when a picture was through it was through.

Q. How do you feel about Godard’s tribute in which he mimics the scene from Some Came Running of Dean Martin in the bath with his hat on?

A. I wasn’t conscious of it.

Q. Have you seen many Godard films?

A. Oh yes, I love him! I think he’s marvelous.

Q. They also say that the café dance scene in Godard’s Band a Part (1964) is a tribute to you.

A. Oh! I didn’t see that picture. I was so busy out here and many of those pictures didn’t play here. But most of Godard’s did and I saw them.

Q. Do you follow the critical waves, the emphasis these days, which is fairly recent in America, on the director, the auteur school…

A. No…

Q. Do you agree that the director would be the most important author of the picture?

A. No. I agree to this extent. Somebody said, if you give a script to five different famous directors, you’d get five different pictures. And I believe that. But as far as the actual [production], it’s a culminative [sic] arrangement. I depends on the writer, the cameraman, the art director and so forth.

Q. If someone did – and I think I do see – common threads running through all your films. And what I said, the Freudian interpretation of obsession working through to liberation, you would say that would still be unconscious.

A. Yes, it would still be according to the story and they way it’s done. The way it’s felt.

Q. So you would say you’re giving shades of emphasis.

A. Yes. If anybody reads a story in a magazine or book, different pictures compete in their minds.

Q. For various reasons, I wasn’t able to see A Matter of Time (1976), so I can’t ask any intelligent questions about it. But I wondered if there’s anything you’d like to say about it.

A. I’ve given it up, disclaimed it. It’s a completely different story than what I shot.

Q. It was recut?

A. Recut? A completely different story! I had an epilogue about [star] Liza [Minnelli] becoming a star, which was unimportant; it was in the [source] book. But they put it on the beginning. That made everything tend to make her a movie star. That was Warner Brothers 1903 or something. This was the story a real person Ingrid Bergman played. She gave parties and was a character – enormously successful. The little chambermaid is obsessed with her and does everything the way she would do it. That’s the story as Maurice Druon wrote it.

Q. What studio did it by the way?

A. AIP, and they had an Italian partner. There’s been an awful lot of trouble at AIP, which I didn’t know. How they would deliberately sink their own picture, I don’t know.

Q. You work with the same performers more than once, besides just Astaire and Kelly. There’s Charles Boyer, Kirk Douglas.

A. I made three films with Douglas, two with Charles Boyer. I’ve worked with an awful lot of people. Katy Hepburn, Spencer Tracy.

Q. Tracy seems so natural an actor…

A. Oh, my God, he’s marvelous…

Q. Did he just walk on and turn it on?

A. Just like that [snaps fingers]. But he arrived at the school of acting – when he ended up he was the antithesis of Marlon Brando. He never had an acting lesson. He just acted.

Q. It seemed so easy for him. You see other people sweat at it. Mitchum also.

A. Yes.

Q. I know that Stradling is the cinematographer you prefer to work with…

A. No, there are many cinematographers. In the MGM days they had them all, they had the best. If one was busy on another picture, you looked down the list and picked the one who was more reasonably connected with the picture.

Q. These would be conditions that you just couldn’t duplicate today.

A. No, no. You go after a person. You have to be a producer nowadays. You have to find the subject, find the writer, find the cameraman, cast it, and then you go to a producer.

Q. After Mayer left MGM, I guess it was Dore Schary and then Sol Siegel as head of production?

A. Yes. I made two films with Siegel.

Q. They both had a reputation for interference I believe.

A. Not as far as I was concerned.

Q. Not even Schary?

A. No. In fact, I made the last picture that Schary did, Designing Woman, and I met him in Europe shortly afterwards.

Q. If you don’t want to name names I understand, but who was the someone in New York that tampered with Two Weeks?

A. Oh, yes, I can never think of his name. But the awful thing is that three weeks later, he was out! I don’t mind naming him.

Q. You enjoyed MGM very much.

A. I was there 26 years and during that time I had no other home. I gave myself completely because they kept so busy.

Q. I guess it was much different there in the Fifties there than it was in the Forties after the divestiture agreement [ed note: the studios sold their theaters, reducing their financial clout].

A. Yes, or the Sixties.

Q. Are you happy with the industry now, would you like to return to any one of those periods?

A. Nowadays the audience has changed. No one can anticipate the audience. They’re absolutely different. They’re so gutted with entertainment on TV and stage and so forth. And violence and sex and so forth. And Star Wars – everyone is trying to get a Star Wars.

Q. You mentioned before talking about surrealism as a movement, how it influenced you, and how Freud influenced everybody in terms of mindset. Do you see yourself as part of a larger artistic movement perhaps in the way a painter in 19th century France might have?

A. I started out to be a painter and was born into the theater. I had given up the theater and everything propelled me into entertainment. And I didn’t resist it.

Q. How do you see the American film historically?

A. American films are terribly popular all over the world and American movie stars are terribly important. I don’t know why. I see wonderful films by Bertolucci, Visconti, and Fellini.

Q. Visconti has a different sensibility from yours but one that’s as acute.

A. He has an enormous attention to detail, the same as I do. But I don’t compare myself to anybody. I don’t consciously do that. It isn’t my nature. No sense of that. A job is a job to me and when I get a story I become involved in it immediately.

Q. Are they any dream projects you haven’t done you’d like to get to?

A. No, I’m open to anything. I’ve worked on so many things that haven’t come off. The life of Bessie Smith, the life of Modigliani; they’ve fallen through.

Q. Again, On a Clear Day, as Stuart Byron wrote, if you wanted to show someone from Mars a typical musical, you wouldn’t show them that one because there isn’t any dancing and no singing for the first half hour. Why isn’t there any singing?

A. It’s the construction. She sings one song at the very opening and it’s just laid out that way.

Q. Does it reflect the repression of the characters perhaps, or at least of Daisy?

A. No. It’s told as a dramatic story, to set it up.

Q. I think your melodramas are as important and as good as your musicals. I don’t mean to overemphasize the musicals. But I would say that if there’s anybody that knows about them, it’s you. Do you think there is a future for them?

A. The five shows I did in New York [before going to Hollywood] were musicals, so I was accustomed to musicals so, I agree, I was essentially a musical director. And a songwriter [producer Freed was a former songwriter] brought me out. But I grew [sic] every kind of story. My imagination works that way.

But I think musicals are going to have to deal with important subjects. Cabaret was important, with the MC as the Hitler character. West Side Story was terribly important because of the style of the dancing and the gangs of New York. That’s what I think musicals will come to. No backstage stories, nothing of that sort.

Q. I was wondering what your taste in music ran to.

A. All kinds.

Q. It’s just that you mentioned West Side Story.

A. That’s a marvelous score. But Rosamund makes another kind of marvelous score. Incidentally, the waltz from Madame Bovary, which is so important in the book – I got a chance to work for the first time with [composer Miklos] Rozsa before the event. I went up with a stopwatch and told him what Van Heflin was doing in the other room [while Jennifer Jones was dancing in the ballroom]. Three times I went back and forth, back and forth, back and forth. It was recorded and we shot to that. Usually, in a dramatic story or comedy, the composer is brought in at the last moment when they see the rough cut. And they have work terribly hard to do it in that time.

Q. How do you determine the rhythms of your scenes generally.

A. That’s intuitional, too. I approach each sequence as if it’s completely different according to the sequence.

Q. Are you working on anything right now.

A. Yes, three things, but I’m not at liberty to say which three things.

Q. I’ve never seen I Dood It (1943).

A. They had shot several numbers which I didn’t agree with. I was rather disappointed in getting that assignment because it was Buster Keaton, who had been worked over. And it was a terrible script. But they gave me two writers and I ended up liking it very much. With the exception of those several numbers.

Q. In famous interviews John Ford and Howard Hawks have disclaimed any attempt to impose any kind of world view on all the films they’ve done. I’d like to ask if you see yourself as a self-conscious artist or an instigator or active agent.

A. No, I only like whether I like the story or not, essentially see something in it that isn’t completely there. I’m sure that’s the way John Ford and Howard Hawks worked. Then I work very, very hard to bring that drive, to make it like no other picture.

Q. Is it easier or more difficult to make a picture today?

A. Much more difficult. Because you don’t have the people to chose from. They don’t get together automatically.