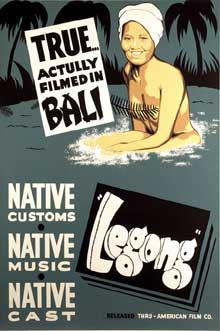

From the mid 1920s well into the 1930s, American and European audiences had a well nigh insatiable appetite for films set in the South Seas – whether they be features, documentaries, or travelogues. One of the most outstanding examples turns out to be a recent rediscovery, Legong: Dance of the Virgins, made by the French adventurer and international socialite, the Marquis Henry de la Falaise. The Marquis shot the film in Bali in 1933, when he was married to the movie star Constance Bennett, and when the island was a favorite vacation spot for the international party set to which the pair belonged.

From the mid 1920s well into the 1930s, American and European audiences had a well nigh insatiable appetite for films set in the South Seas – whether they be features, documentaries, or travelogues. One of the most outstanding examples turns out to be a recent rediscovery, Legong: Dance of the Virgins, made by the French adventurer and international socialite, the Marquis Henry de la Falaise. The Marquis shot the film in Bali in 1933, when he was married to the movie star Constance Bennett, and when the island was a favorite vacation spot for the international party set to which the pair belonged.

Yet, despite the potential for dilettantism that would seem to threaten the production, the 55-miinute Legong is a fascinating and rewarding production for two reasons. First of all, it is a superior example of the island romance, paying close heed to several aspects of Balinese culture while telling a solid, if extremely familiar tale. Secondly – and probably more significantly – it tells us what appealed to people back in 1933 about Balinese life or at least what they took Balinese life to be.

Before anything else, Legong is a significant technical achievement. One of the last silent films to be commercially released, it incorporates dance, subtle pantomime, and the peculiar nature of silent-film editing into an all-encompassing narrative whole. It is also one of the last films to be shot in two-strip Technicolor. Briefly, Technicolor is – or was and, I believe, is again – a dye transfer process, not merely a photochemical one. For two-strip Technicolor, only red and green dyes were used, which, in the case of Legong results in a film that is predominantly green, brown and orange. The coloration is experienced less as a lack than as a suitably exotic accompaniment to the film’s setting. We can enjoy this experience thanks to the UCLA Film and Television Archive, which sought out various incomplete versions of Legong in three different countries, put them together in a complete version, and preserved it.

The life is, as most South Sea films presented at the time, inherently edenic. The weather is always balmy and the natives, who walk around stripped to the waist, mostly young and beautiful. This is De la Falaise’s first cultural intrusion; not the climate (though he may be overlooking a rainy season for all I know), but in the age and appearance of the Balinese. Aside from a couple of old-women gossips (a prejudice in itself) and a courtly old man or two, De la Falaise keeps anyone over, say 25 years away from his camera. All the people who get within sight of his lens are young and good-looking, Adams and Eves as it were.

Cultural activities are similarly segregated, though we do get to see a lot more of them than we do of the people. As you’d assume, we see their houses and other constructions (a footbridge over a towering river gorge is particularly impressive). We get a look at the board games people play in the leisure time; how they go about buying palm wine. We see them carrying four to ten-foot high baskets of temple offerings on their heads. We see a woman pounding rice, but – aside from a panning shot that briefly glimpses what could be tiered rice paddies, we don’t see where the rice comes from.

Indeed, we don’t see any farming nor any fishing. Some cattle move about in the background and we see a cock fight; at the end of the movie, a boat puts out to sea. So we can assume all these subsistence activities occur. But never on the screen.

Showing the Balinese actually having to wrest their existence from the soil and sea would disturb the impression that they are living in a paradise. De la Falaise’s Balinese toil not.

Every paradise must have its serpent, though, and Legong gives us a peek at its in its opening title, which recounts a Balinese saying aimed at young maidens (I don’t vouch for its authenticity): “Should love enter thine eyes and go to they heart, beware. For should he whom thou choosest not return thy love, thy gods will frown and disgrace will befall thee.”

The plot, enacted by an all-native cast, follows the romantic travails of Poutou, a “chaste temple maiden” and dancer, who falls for Nyong, a newcomer to her village. Nyong is a player in the gamelan (more on this marvelous musical instrument later) and at first seems to return Poutou’s affections. But, one day, he meets Poutou’s younger half-sister, Saplak, on the road, and falls for her, a development that leads directly to Poutou’s unbearable humiliation.

Poutou’s status as a dancer is part of Legong’s chief interest, which is Balinese dance; in fact, the title refers to a dance that Poutou, who has just learned of Nyong’s romantic defection, performs under strenuous emotional strain. Aside from that climactic performance, the movie features other performances, including a narrative dance about a witch, a prince she turns into a lion, and the royal retainers who attempt to free him from the spell. Aside from their precise steps, hand movements and postures, these dances also feature ornate – sometimes fantastically ornate – costumes that are in marked contrast to the casual dress, or undress, of everyday Balinese life. And while it’s true that De la Falaise tries to impose “extra” (plot) meaning on the legong dance, every one of them is inherently beautiful, well photographed, and respected.

The other native art displayed in Legong is the gamelan, which is sort of like a Balinese xylophone or, rather, a collection of xylophone-like instruments, lined up and in rows, and including cymbals (I’m going by what I could see in the movie). Some number of musicians play the gamelan at the same time so that strange, ringing, metallic harmonies result.

Of course, since Legong is a silent film, we can’t hear the gamelan in the movie. But an alternate sound track (alternate to the movie’s conventional period score) let’s us hear a gamelan very nicely. The Club Foot Orchestra, known for accompanying silent films in San Francisco and Los Angeles, has combined with the Gamelan Sekar Jaya to produce an exceptionally beautiful score that combines largely strings and clarinet, on the one hand, and gamelan, on the other. The combination is much smoother than you might expect and hauntingly evocative.

Back to Poutous unhappy fate, though. Legong is far from the only South Seas romance to smite its own paradise with self-imposed tragedy. It’s far more common than otherwise. De la Falaise simply can’t bring himself to imagine a group of people living outside the strictures of his own psychosexual world. If people enjoy a life of leisure and near nudity, then, the movie insists, infelicitous coupling is nearly bound to happen. It will be so common, in fact, that it will find its way into the local folklore.

This isn’t to totally devalue Legong, either as a film or as a window on Balinese life. But (aside from making one want to take Margaret Mead’s side of things), it does remind us that there’s a double perspective that attaches to any work of cultural “observation.”

The DVD package of Legong also comes with a “B side,” Kliou (The Killer), which De la Falaise shot in Vietnam in 1934. Set among the Moi tribes people in the country’s Annan region, Kliou wears its biases much more openly; the opening titles refer to the Moi as “barbaric” for example. De la Falaise himself appears in a framing device as himself, a great white hunter, who returns to a French outpost where he tells an officer the story that takes up the film to follow.

This time out, the tale itself – a villager’s hunt of a man-eating (the movie’s description) tiger – takes up nearly all the film, with almost no time spent on the cultural life of the Moi. Clearly, this is because De la Falaise feels they don’t have much of a culture and he valorizes the young man, Bhat, who goes after the tiger as the only hunter among a village full of farmers.

This is a nice little complication, of course. As we all know from school, agricultural production represented a step up the ladder of civilization from hunting and gathering. But in the modern world, a man distinguishes himself – as does De la Falaise – by adopting the role of hunter, especially big game hunter (De la Falaise presents a couple of elephant tusks to his officer friend). Thus the French aristocrat and socialite identifies himself with a nearly naked young man with a cross bow.

De la Falaise’s talent for nabbing terrific footage doesn’t let him down, though this time out he clearly has staged some of his scenes, especially of the tiger. Several scenes of elephants – including a couple of bulls galloping towards the camera – seem wild, however, as does the menacing glace of a water buffalo.

Curiously, De la Falaise presents more of the Moi working life than he did of the Balinese. Perhaps because he respected the Moi so much less than the Balinese (the Balinese have priests; the Moi have “witch doctors”) he doesn’t mind showing them scratching a living from the land. In any case, we do see the Moi at work in their rice paddies with beasts of burden.

Although Kliou was also shot in two-strip Technicolor, the DVD edition is in black-and-white. It’s very existence, though, is a bit of a triumph as the movie was apparently considered lost for many years.

If you can’t find Legong, Dance of the Virgins at your local video store, try getting in touch with the company that has put it out, Milestone Films at www.milestonefilms.com.