Nonagenarian Portuguese filmmaker Manoel de Oliveira has been enjoying one of the most extraordinary careers in cinema history. After a directing career that went through fits and starts, he settled down into his productive years in his 70s and has been producing a steady stream of provocations, curiosities, and masterpieces ever since.

Nonagenarian Portuguese filmmaker Manoel de Oliveira has been enjoying one of the most extraordinary careers in cinema history. After a directing career that went through fits and starts, he settled down into his productive years in his 70s and has been producing a steady stream of provocations, curiosities, and masterpieces ever since.

Oliveira made I’m Going Home in France in 2001 with the distinguished French actor Michel Piccoli, himself on the shady side of 70. He’s directed at least two films since then, a measure of productivity that would be impressive in a filmmaker of any age. Unfortunately for Americans, they’ve been unable to see most of Oliveira’s work thanks to the exclusionary oligopoly which controls U.S. distribution.

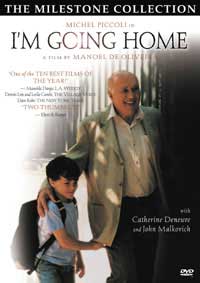

Luckily, Milestone Film & Video (www.milestonefilms.com) has released I’m Going Home on a DVD that includes an interview with Oliveira. The interview makes for a fine garnish but the main repast is the film itself, a superb work that bears rewatching.

Although Oliveira is intellectually vigorous, old age has inflected his filmmaking, though in only the richest imaginable terms. This film is ultimately about the weariness of grief, a universal feeling that emerges in clear, shimmering terms only after we witness it through the experience of a single man, a well-known French stage actor, Gilbert Valence (Piccoli). Crucial to its understanding as the work of an aged sensibility is that it’s not a lugubrious or lachrymose effort. Oliveira has spiced the work with lightness and humor, a mixture that can be spied in the effort of many elder directors (Hawks’s El Dorado, Renoir’s Le Caporal épinglé). The end result is not just a more approachable film, but a vision of life that is at once expansive and paradoxical.

The film opens with Valence on stage before a rapt audience performing the lead role in Ionesco’s Le Roi se meurt/Exit the King. It doesn’t require any familiarity with the Absurdist playwright’s work to see that this comic drama about a mentally failing, formerly tyrannical and old king is at least partly about the vicissitudes of aging. Valence’s king is trying to hold onto his position of paterfamilias amid a family and court itching to get out from under his hand.

But these painful, but nostalgic ailings of senescence are to be denied Valence. Once offstage he’s met by men who tell him – in a sequence held offstage – that his wife, adult daughter and son-in-law have died in a car crash. Valence has been left alone and untended as well as unrebelled against (a perk of seniority). Additionally, he is compelled to stand in as the parent of his orphaned grandson, Serge.

From this scene, Oliveira progresses to some months later when Valence has settled into a routine. Crucially, though, as the filmmaker shows us his possibly tragic, certainly distracted actor going through his day, we first either see him without hearing him or hear him without seeing him (at least seeing no more than his shod feet). This is a measure of both Oliveira’s discretion and of his presentation of an unassembled man. When Valence does emerge into a fully seen and vocalized, we don’t see a man in pain but a grouchy oldster who has submerged his angst within a careful routine.

Oliveira shows us the routine with Tati-like humor. Valence is a daily visitor to a café where he invariably sits at the same table, drinks a coffee and reads the leftwing daily Liberation. And each time he departs, his place is immediately taken by the same businessman carrying his own newspaper, the rightwing La Figaro. Valence has found a slot and he’s quite comfortable there, behind glass like a pinned butterfly.

Valence uses his performances, as moving as they evidently are, to continue the process of emotional submergence. We see him on stage in The Tempest, doing the famous Act IV, Scene I “we are but the stuff that dreams are made on” soliloquy. It’s another fantasy for Valence, in which the actor can emote a simulacrum of sadness, but do so as a father and father-in-law, as if he were in the state he was before he left the stage during the Ionesco performance.

To understand the film, it’s important to understand Oliveira’s attitude towards theater. It’s clear the director does not view the theatrical stage as different from any other forum in life. He goes further than the clichés which hold that the stage is a metaphor for life or that we are always “acting” in our quotidian existence. As Oliveira presents it, a man may on stage or off it, but he is always the same man undergoing the same life and enduring (or enjoying) the same emotions as he would offstage. So Valence is Valence, whether he is upbraiding his agent for a bad job or musing aloud as Prospero.

Oliveira’s beautifully measured presentation of Valence rolls us gently down to his moment of crisis. A visiting American filmmaker, played by John Malkovich, needs to find a last-minute replacement for an actor who was going to play Buck Mulligan in a film adaptation of James Joyce’s Ulysses. Mulligan is in his 20s, so Valence would seem entirely unfit for the part. But the director casts him anyway and it’s under absurd make-up that Valence must finally confront his exhausting grief.

Oliveira understands that these feelings, if they are to be captured honestly, must be viewed obliquely. We do see human suffering on the one hand, but just as Valence enters his own soul and an off-center angle, so we see the emotions as if with our peripheral intellectual vision. This makes both Valence’s individual suffering, and the universality of it, simultaneously comprehensible.

It’s that profound comprehension that makes I’m Going Home the masterpiece that it is. Less explainable than experientially powerful, it’s a remarkable experience.