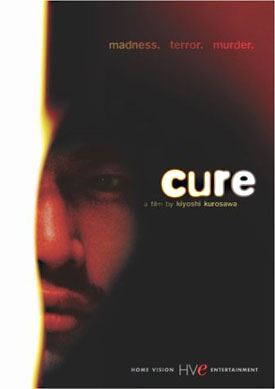

Despite the fact that it left audiences rapt and creeped out at the 1998 Toronto International Film Festival, and then again at Toronto in 1999, Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cure never hit with American audiences when it managed a small release in the United States a few years ago.

Despite the fact that it left audiences rapt and creeped out at the 1998 Toronto International Film Festival, and then again at Toronto in 1999, Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cure never hit with American audiences when it managed a small release in the United States a few years ago.

That might be because the only Japanese movies that make it through the “free-trade” barriers that keep most foreign films out of the U.S. are either some of Beat Takeshi’s or the grotesquely violent and sadistic chop-‘em-ups that have developed a cult following.

Cure has its share of bloodshed (and one moment where the squeamish may want to shield their eyes from the screen) but this occult thriller thrives thanks to an atmosphere of dread and alienation which settles over it like a billowing, evil fog.

The plot is fairly simple, though bizarre: Police detective Takabe (Koji Yakusho, known to popular audiences from Shall We Dance and cineastes from The Eel) investigates a strange series of murders. A husband kills a wife, a policeman his station mate, and various other people their intimates and acquaintances all seemingly on the whim of a moment. Some can’t understand how they could have possibly yielded to such a monstrous and fleeting impulse while at least one insists he was justified in the face of his victim’s annoying habits.

The only link among the murders – aside from their lack of understandable motive – is the presence of a mysterious young man who may or may not be named Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara). Mamiya suffers from an extreme case of amnesia; he not only can’t remember who he is, but he forgets bits of conversations moments after they occur, a frustrating habit for a police interrogator.

After spending some time in Takabe’s custody, though, Mamiya does seem to recall some incidents from the past, but they all have to do with Takabe and his relationship with his wife, who is suffering from advancing dementia. Takabe may be on the verge of discovering more than he counted on but, for the sake of your enjoyment, the synopsis ends here.

Watching Cure may leave you with the impression that Kurosawa specializes in occult thrillers. But despite the film’s disturbing effectiveness, he doesn’t. Kurosawa was the subject of a small retrospective at the 1999 Toronto Festival, the year after I saw Cure at its initial screening there. According to the notes, he started his career in the mid-‘80s but, along with other burgeoning filmmakers of the period, found there was no financing to follow up on his initial work. So he turned to direct-to-video and genre filmmaking until he managed to make it back into features in the late 1990s. Though he had had films shown at Venice, Berlin and Cannes, as well as Toronto (making him four-for-the-Big Four), I haven’t encountered any of his work since.

What was on view at Toronto was almost crazily diverse. His early film, The Excitement of the Do-Re-Mi-Fa Girl, was made for producers expecting (and getting, to a point) a “pink,” or pornographic film. Yet it resembles nothing so much as Jean-Luc Godard’s Made in U.S.A., though with considerable accounts having to be made for its Japanese-ness. Essentially it follows a young woman onto a university campus where her encounters with sexuality are tested against revolutionary ideas.

Though less free-form, 1999’s Barren Illusion is more hallucinogenic, in that two of its main characters -- an unsuccessful music producer and his girlfriend, a post office worker who steal packages -- spend most of their time on drugs or having violent fantasies.

That same year’s Charisma, though, leaves all that behind him in its enveloping strangeness. Various people in rural Japan fight over the fate of a huge, evil-looking, leaveless tree which is, in fact, evil.

Kurosawa’s style is as shifting as his narrative material, beginning with the quick cutting of Do-Re-Mi girl and progressing to the long-take stillness of Cure. That’s not to say that Cure is conventional. Viewers who like their climaxes to arrive all neatly tied up will find this one particularly maddening. For as Detective Takabe moves in closer to the heart of the mystery, the action skips forward here and there. Solutions turn into ambiguities and back into mysteries.

That, of course, is how the larger search for knowledge actually works. Kiyoshi Kurosawa does, then, solve an issue bigger than a murder mystery.

Cure is put out by Home Vision Entertainment. If you can’t find it in the stores, contact them at http://www.homevision.com.