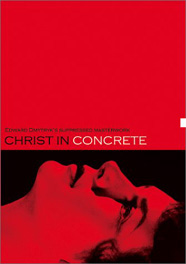

Hollywood director Edward Dmytryk had already served a year in jail for long-severed ties to the Communist Party, USA when, in 1949, he moved to England where he made three movies. One of them was Christ in Concrete which was released back home under the titles Salt to the Devil and Give Us this Day, the latter being the rubric under which it has largely been known since.

Hollywood director Edward Dmytryk had already served a year in jail for long-severed ties to the Communist Party, USA when, in 1949, he moved to England where he made three movies. One of them was Christ in Concrete which was released back home under the titles Salt to the Devil and Give Us this Day, the latter being the rubric under which it has largely been known since.

Unfortunately, thanks to a slip-up in copyright, complete, good quality prints of the movie have been few and far between. Now David Kalat has released a restored DVD version of the film on his Allday Entertainment label, which is distributed by Image Entertainment.

The film is no masterpiece, but it’s rewarding on several levels, a strange mixture of naïveté and sophistication and a superior example of production design and of Dmytryk’s mastery of editing, a skill that, strangely, eluded his grasp when he decided to name his former party associates and return to Hollywood. Dmytryk had two important American collaborators on the project, the screenwriter Ben Barzman and his leading man, Sam Wanamaker, each of whom were on the run from the Blacklist though, unlike Dmytryk, neither had done time for their political beliefs.

Based on a proletarian novel by Italian-American writer Pietro Di Donato and set in New York City, Christ in Concrete, which features a semi-flashback structure, focuses on the travails of Geremio (Wanamaker), an immigrant bricklayer undone by his own and his wife’s ambition. Geremio’s goals don’t amount to too much more than a generalized wish to be well-to-do and respected, a boss if possible. But his wife, Annunziata (Lea Padovani), wants the house that Geremio promised her at their engagement and even deceived her into believing he owned during the first week of their marriage. This deception cleaves sharply between them, a wound that never quite heals.

The action begins during the 1920s, when a laborer had a reasonable expectation of earning some money, and continues into the Great Depression when, now a father, Geremio sees his ambitions come crashing down with the financial markets. This, along with his sharply disappointed wife, leads him to accept the job of foreman on a job he knows is unsafe. Despite that he lures his old friends to work the site, setting up a climax of, as the title implies, humiliation, death and redemption.

The mix of Marxist and religious doctrine was not, and had never been, unusual, though never particularly palatable. Here it adds to what is admittedly an overheated rhetorical stance, not so much in terms of political doctrine, but in the declaration of what, for a better term, you might call the old "dignity of man" stuff.

The purely Marxist aspect of the film reaches a reasonably high level of sophistication. True, there’s some of the Clifford Odets stand-up-and-be-counted nonsense, but Dmytryk and Barzman were no simpletons. They paid good heed to Marx’s notions of alienation – from self, family, work and society – and they integrate those ideas quite well into the drama.

Christ in Concrete was made as films set in New York City were beginning to be shot on location. The historic Force of Evil with its stunning views of the city by dusk – made by the blacklisted Abraham Polonsky and starring the about-to-be blacklisted John Garfield – had been made just the year before. And Christ’s own opening sequence had been shot by a unit dispatched to the city by the movie’s British producers.

So Dmytryk’s film was one of the last to create the city almost entirely on soundstages and a backlot and it does so beautifully and evocatively. The art director was the London-born Alex Vetchinsky, a man whose career seems marked more by longevity and productivity than any high artistic marks, though he did design The Lady Vanishes and A Night to Remember. His work on Christ in Concrete makes the film worth seeing all by itself.

Additionally, the activity at the work sites, a wedding sequence, and social scenes in general allow Dmytryk to stretch his editing skills. The montages of machine and men functioning together at building construction are particularly well done; you can feel the energy that must have consumed the former cutter as he sat down to his favorite job.

Barzman stayed in Europe and went on to make many films with Joseph Losey and one or two with Jules Dassin and John Berry, other escapees from the political witch hunt. Dmytryk, as noted, went home and became an entirely different type of filmmaker, both in terms of the nature of his projects and in the manner in which he shot his films. One has to wonder to what extent Christ in Concrete was a "good-bye to all that" for the former Communist, to what extent Marxism and montage went hand-in-hand for his creativity’s sake. For although he always insisted otherwise, all politics aside he wasn’t half the filmmaker after he returned from England as he was before he left.