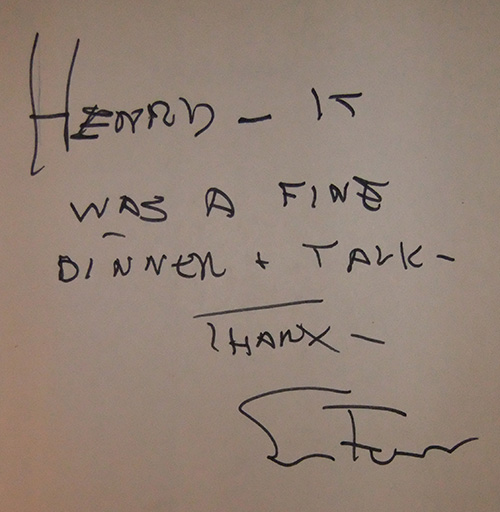

As it pretty much says in the article, this interview was conducted over Thai food in Boston in 1986. At the time Fuller was in his second eclipse. The first had ended when auteurists celebrated the uniquely bold language of his movies. Unfortunately, the wave of enthusiasm had broken just about the time The Big Red One came out in a truncated version. No one except the usual critical minority raised a hue and cry when White Dog was nearly put down for good by Paramount. Luckily, the college film groups, museums and cinematheques of the world maintained their interest throughout. Hence my dinner with Sam.

Sam Fuller’s films unfurl in a world where art erupts with nightmare and memory. They are inimitable creations. What other director could open a picture with a bald prostitute beating a man to death with a phone (The Naked Kiss, 1964), conjure up a Western town that’s under a woman rancher’s erotic spell (Forty Guns, 1957), or pick the most infamous backshooter in American history as the hero of his directorial debut (I Shot Jesse James, 1949)? Fuller’s characters are always at war – with the world and with themselves, much as Fuller himself is. After working years in the newspaper business and as a pulp novelist and fledgling screenwriter, he joined the army in World War II, serving as an infantryman in North Africa, Sicily, France, Germany and Czechoslovakia, and winning a Silver Star, a Bronze Star, and Purple Heart. For years after his return to Hollywood, Fuller would battle executives trying to tone down his vision of war in Fixed Bayonets (1951), The Steel Helmet (1951) and Verboten! (1959) until finally in 1980 he got the chance to bring The Big Red One to the screen. Even then his film was doctored by a worried studio so that only half of the original four-hour film was released.

Controversy still dogs Fuller. His film White Dog (1982), a drama about a dog that had been trained to attack black people on sight and is taken into care by an idealistic white girl, was shelved by Paramount, ostensibly because people might find it offensive. One can only wonder why the studio would take on a Fuller project in the first place, since his reputation as a strong-willed, strong stomached director is so well-known. Fuller was in Boston was in town recently for the Museum of Fine Arts’s visiting-directors series. We were able to sit down over dinner while he reminisced about his days as a successful screenwriter angling for his first directing job.

After the war, Fuller had resumed his writing career. “I did ghostwriting on some of Otto Preminger’s films,” he recalled, “and if you want to know which ones they are, you’ll have to pay me as much as they did to do the writing. The writers I did it for were friends, they had their own reasons, personal reasons, why they couldn’t do it. Preminger wrote about it once, said he had his ‘Sergeant Fuller’ do some writing. He promoted me – I’d only been a corporal. That’s why I always liked Otto.”

In Hollywood, it’s possible for filmmakers to collaborate on a movie without even meeting. Such was the case with one of the town’s stranger collaborations, when the robust, rowdy Fuller wrote a screenplay filmed by the reserved, intellectual Douglas Sirk. On top of that, studio-enforced script changes ignited a feud. The movie was Shockproof (1949), a film noir starring Cornel Wilde as a parole officer who falls for, and goes on the run with, one of his female charges (Patricia Knight).

“My original script opened with the parole officer sitting in his office, and he’s talking with another fellow. And he’s saying, ‘I’ve studied psychology, criminology, and sociology and none of it matters. I can tell just by looking at someone whether they should be locked up. And if I think they belong out, no matter what they’ve done, even killed someone, then I’ll let them stay free.’

“So a parolee walks into his office and says, ‘I didn’t report last week, I’ve been out of town, but I didn’t do anything wrong. Please give me a break and don’t send me back.’ The officer says, ‘No, you’re going back.’ ‘Please give me a break.’ ‘No.’ So the guy runs past the officer’s desk, leaps through the window, glass breaking and everything, and falls 15 stories to his death. Then you run the opening credits.

Fuller went on to describe the day the heroine gets out of prison. “You see these feet coming out onto the sidewalk and the camera pans up a little to her ass or whatever. Shows her from behind. And she gets into a car and drives away. Now, later, the parole officer takes her to this chocolate factory and gets her a job. And the guy who runs the place doesn’t want to give it to her, but he does. Then you see her walking around and you see her ass again – and it’s covered with chocolate handprints. So you can tell what’s going on. So the boss of the place comes up to her while she’s working on a scaffold over this huge vat of boiling chocolate and says, ‘If you want to keep this job, you’ll have to fuck me.’ And she says no, and they fight, and she throws him into the vat of chocolate. And he boils to death. In chocolate. Well, the parole officer comes and he hears her story and he says, ‘Okay, I believe you, you can stay out of prison.’

“See, my original script was called The Lovers, [which] was important. Because the lovers weren’t the cop and the woman, but her and her old boyfriend, who’s a crook. And she sides with the cop because he’s better in bed and he can keep her out of prison. But she’s still in love with her old boyfriend, she just can’t afford to have him in the way anymore. So she uses the cop to get rid of the boyfriend. And the point of the picture was the power that this cop has over other people, and how they have to learn to deal with it.”

The story exemplifies how Fuller was the rare writer/producer/director with the gumption to bring such hard-boiled material to life. “[Head of Columbia] Harry Cohn gave the script to Sirk,” Fuller continued. “Then [Cohn] got another screenwriter, Helen Deutsch, to work on it. And it was ruined. Took out everything and practically made it a woman’s romance picture. Which there is nothing wrong with, except that it’s not what I wrote. So for years I thought Sirk had had these changes made and whenever I gave an interview and they asked me about it, I’d say, ‘Oh, yeah, that stupid son of a bitch ruined my script. Stupid son of a bitch.’

“So one day in my home in Paris, my wife comes up to me with a copy of Cahiers du Cinema and says there’s an interview with Sirk. I say, ‘That son of a bitch, get it away from me.’ And she says, ‘No, you’ve cursed him out all these years, now you listen to what he has to say.’ It turned out he had loved my script and had been mad as hell at the changes. So when I heard him say he loved my script, I said, ‘Well, he is brilliant after all!’

“See, there’s this thing called American writing. American writing. And when I wrote The Lovers, I had them saying ‘fuck’ and everything else. You know they’re going to take it out, but you should have it in there when you write it, because that’s the way people talk. Tough. And in American writing you keep it tough. Lots of action. And I’m proud that that’s the way I’ve always written.”